What were the Major Loopholes in the Data Protection Bill that led to its Withdrawal

Posted On Monday August 22, 2022 Shiv , under Governance Policy

Abstract

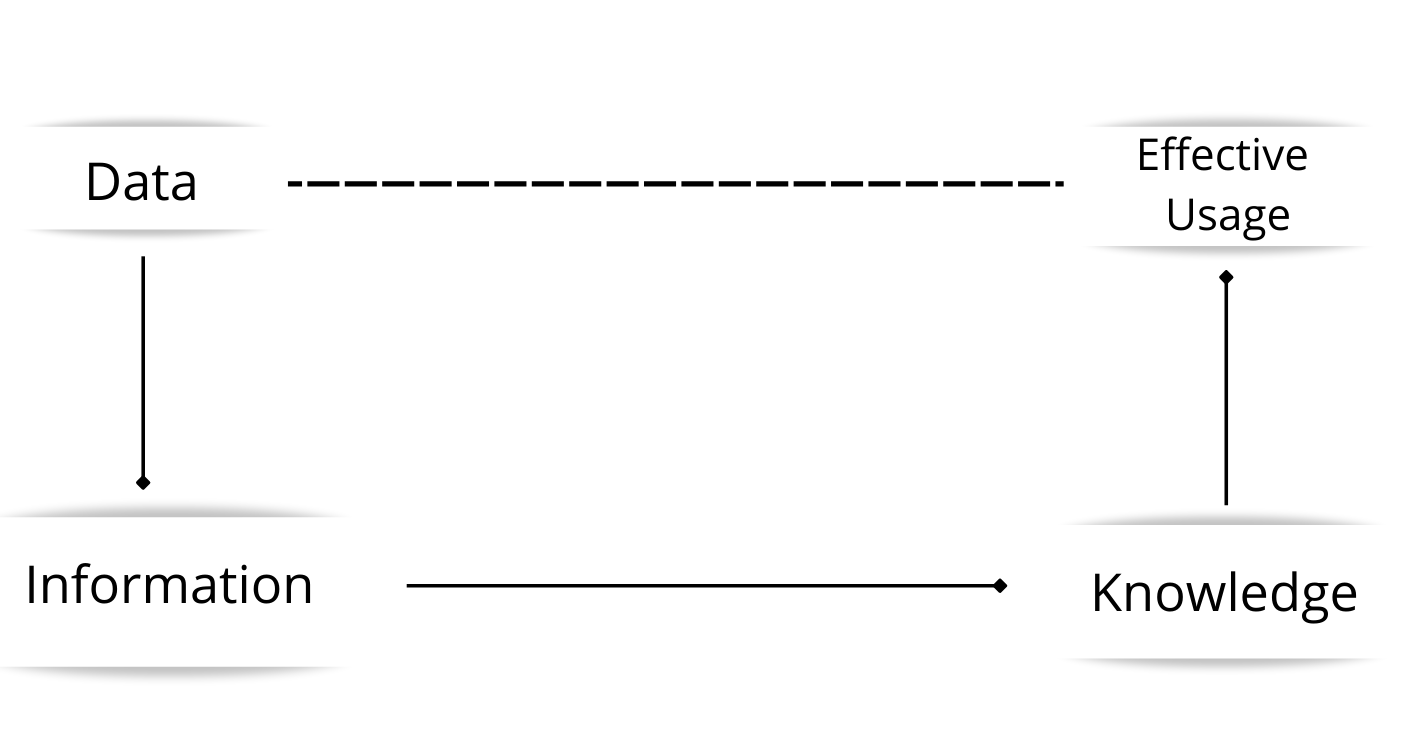

India is heading towards becoming a digital economy where data is extremely essential for governments, and companies to run in the 21st century. India is generating humongous data - 150 exabytes annually. The data, an intangible asset can be consumed and exploited for multiple purposes like providing efficient and personalised services, effective management of disasters etc. The value chain of data can be described as:

Figure 1: Steps involved in Data cycle for Effective usage

Source: REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE PERSONAL DATA PROTECTION BILL, 2019

The data technology can be broadly classified into two categories

1) The technology used in Capturing and Storing Data.

2) The technology used in Processing Data.

It is mandatory to organise data for its better use, hence there is a requirement for a robust design and setup which can lead to the unification of data sets from the public-private sector and academia, data from these domains can be absorbed as per requirements, and digital technologies can be applied to the selected data sets for improving products and services. To do so, there is a requirement for Data management policies that can address the accuracy, privacy, and security of the data, along with defining data ownership rights. The right data infrastructure and governance mechanism is a precondition to unleash the power of data.

As per the statistics of the UN, 128 countries out of 194 have data protection regulations in place. However, India has also started its journey in creating stringent Data Protection Laws.

This paper analyses key aspects of the Personal Data Protection Bill, by also focusing on examining recommendations by the Joint Parliamentary Committee. To strengthen India’s first data protection law, this paper also provides recommendations on required provisions of the Draft Data Protection Bill, 2021.

The Journey From The Personal Data Protection Bill’19 to Draft Data Protection Bill’21:

The genesis of the Data protection regime lies in the Aadhar Data Breach case of 2017 -

K Puttaswamy Vs. The Union of India case, the supreme court judgment for this case recognised the right to privacy as a fundamental right under Article 21. Then The central government in 2017 constituted a Committee of Experts on Data Protection which was headed by Justice Shri B.N. Srikrishna. The committee submitted its report to the government of India in 2018. After various consultations and deliberations with stakeholders, the central government started drafting the Personal Data Protection Bill. The bill was formulated on the basis of Justice Shri B.N. Srikrishna committee’s report was modelled on the European Union’s General Data Protection Regime (GDPR); GDPR has played a vital role in the formation of the Indian Data Protection regime. The arrival of GDPR was a game-changing moment for Europe as it recognised data as the asset class and economic driver of Europe. It has also accelerated the discussion on the importance of consent in a data driving economy. The people of Europe are the priority stakeholders for GDPR, protecting their personal data inside and outside Europe is the prime concern.

Significant Features of GDPR:

1) Informed consent:

- GDPR aims to simplify the consent mechanism for users, as long and complex consent guidelines create consent fatigue where users are tempted to ‘Agree’ without having complete knowledge regarding stated consent guidelines.

2) Breach Notification:

- In the case of any data breach, the governing authority is required to be notified within 72 hours, aiming to inform concerns so that they can take required steps to protect their information. This provision is one of the most vital user-friendly provisions of GDPR.

3) Automated decision-making:

- As per this feature, users get the choice to keep their data out of automated decision-making, where their data is processed by an algorithm to understand users’ behaviour on the basis of their data. This will impact all the algorithmic media.

4) Citizen awareness:

- The fundamental objective is to create awareness of GDPR, for maximum usage of the act. As per one EU survey, Eurobarometer, 73% of Europeans have heard about at least one of their rights, however out of every ten EU citizens, not even seven are aware of their rights.

The first draft of the Personal Data Protection Bill was tabled on 11th December’19 in parliament. The bill then was with the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) for recommendations, the JPC provided 81 recommendations along with 150 drafting corrections and improvements in various clauses of the bill. Finally, after two years on 16th December’21, the JPC submitted its report to the government of India followed by the creation of the Draft Data Protection Bill 21. On 3rd August, 2022 during the monsoon parliamentary session, the government withdrew the Personal Data Protection Bill’ 19, the government stated that the Joint Parliamentary Committee has provided a comprehensive legal framework, in order to fit the current bill into this framework, the new bill will be presented.

The bill provided the framework for protecting citizens’ personal data from entities that collect and use the data. In the bill, certain obligations were imposed on Data fiduciaries, the companies which collect, use and process the data of the people. The bill has also given certain rights to Data Principals, the one who shares their data with the data fiduciary. However, there was a provision for establishing a Data Protection Authority to regulate and oversee data breaches. This paper will discuss prominent loopholes in draft Data Protection Bill 2021, which came into discussion after the Joint Parliamentary Committee’s recommendations. The paper analyses the practical applicability, the existing gaps and provides possible policy recommendations.

Key Recommendations by The Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC):

1) Include Non-personal data:

The JPC suggested including non-personal data within the ambit of data protection and changing the bill name from Personal Data Protection bill to “Data protection bill”. An expert committee chaired by Infosys co-founder Kris Gopalakrishnan was appointed by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) to recommend a framework in order to regulate Non-personal Data in India.

The report submitted by the Kris Gopalkrishna committee in December 2020 includes a detailed aspect of Non-personal Data. The committee classifies Non-personal data into three types:

1) Public Data:

- Anonymised data of land records, public health information, vehicle registration data etc.

2) Community Data:

- Datasets collected by municipal corporations, datasets comprising user information collected even by private players like telecom, e-commerce, ride-hailing companies

3) Private Data:

- Inferred or derived data/insights, involving the application of algorithms, proprietary knowledge

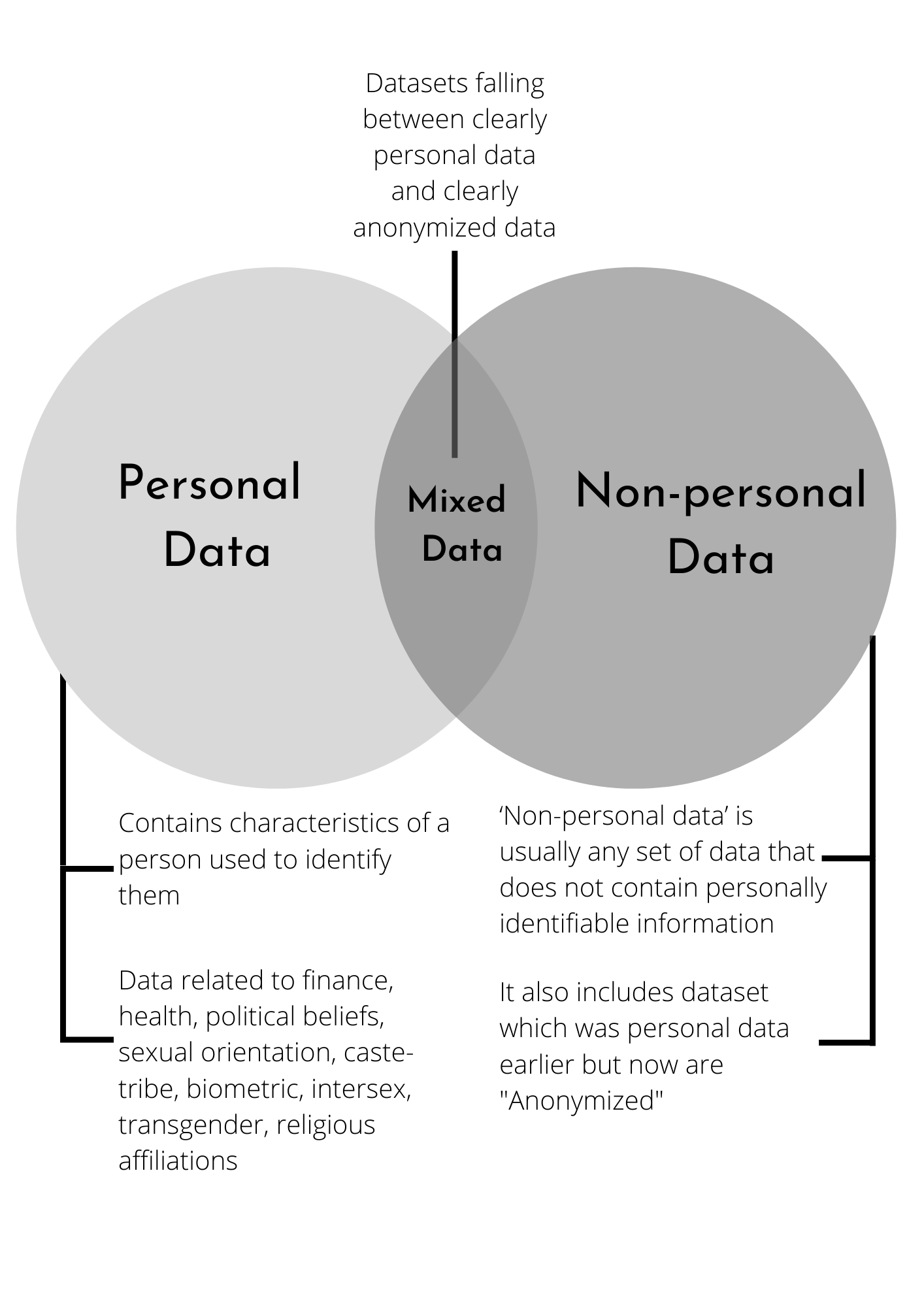

Non-personal data can also affect privacy according to the JPC. However, The bill defines “Personal data” as any data that may contain any characteristics or traits of a person and can be used to identify them, it also defined “Sensitive personal data” - A subset of personal data, which includes data related to finance, health, political beliefs, sexual orientation, caste-tribe data, biometric data, intersex data, transgender data, religious affiliations.1 “Non-personal data” is a set of data that does not contain personally identifiable information, including data that used to be personal data and has been ‘anonymised’, to remove information in a way that the person to whom the data relates cannot be identified. Anonymised data can be converted into identifiable datasets. Usually, any data that does not come under the definition of personal data is non-personal data.

The purpose of including Non-personal data under the regulation is an out of concern approach for citizens’ privacy, however, the feasibility lies in its applicability. India is the only country in the world that included both Personal and Non-personal data under the same regulatory framework. Even though the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) only deals with personalised data, the GDPR regulation adopts a binary approach to differentiate between Personal and Non-personal data2.2 But the reality operates between clearly Personal and clearly Anonymised data, often termed as Mixed data sets. The PDPB alluded to mixed datasets falling under Personal data protection standards, the same application as GDPR.

Figure 1: Relationship between Personal, Non-personal, and Mixed datasets.

Even after knowing the vulnerability of anonymous data like its technical feature of getting converted back to the identifiable dataset and its scope of exploitation, countries across the world have not regulated it, because by exempting anonymised data from the law may encourage companies to anonymize more, leading to reduced personal data processing and enhancing overall privacy. It is again a tedious process for firms to protect Non-personal data also along with personal data, which can affect small enterprises since they may not have a solid infrastructure to protect Non-personal or Anonymised data, with a lack of such required infrastructure big enterprises may not collaborate with them.

The community non-personal data brings complications unlike public and private Non-personal data which is distinguishable on the basis of the entity collecting it. The community's non-personal data rely on the basis of who the data pertains to. The reason behind rooted complications is the different criteria on which a community is being formed. The DPB’21 framework was aspiring to empower communities and enforce their right over Non-personal data via the institutions of Data trust, and the fiduciary duties exercised by data trustees acting in the interest of communities, ensuring equal rights to the community is the prerequisite for the infrastructure of data trusts to work.3 Once the rights are served to communities over their data, they expect a body or institution which can represent their rights to data fiduciaries. It is evident that if data fiduciaries themselves try to create data trustees by ensuring the rights of users then it will create bias in the whole infrastructure. however, insights on defining community are still lacking in the JPC’s report.

Additionally, there are certain concerns over the vague definition of governance of non-personal data by data trust:4

- The relationship between different stakeholders is not defined when it comes to creating an institution of data trust, without establishing a proper relationship between stakeholders, proper communication will not take place.

- It is still ambiguous who should act as data trustees, anyway, the government agencies are considered as default data trustees but the outcome of this is dependent on the relationship between the community (beneficiaries) and data trustees (government agencies), it may lead to the politicisation of data trust and community may not get proper representation and justice.

- Functions of data trust are not contextualised in the report - applying the same administrative model of data trust in every situation may not serve the purpose. Its functions are based on the type and needs of the community.

- As data trustees will be acting as a liaison between data fiduciaries and data trust (beneficiaries) - the relationship between them is not defined.

There must be established regulations and working standards for data trust, such as:

- The infrastructure needs to be regulated in such a way that responsibility is also assigned and freedom to work is also ensured.

- The relationship between data fiduciaries and data trustees seeks transparency, as data trustees are vulnerable to getting influenced by data fiduciaries.

- The DPA should dedicate one of its agencies to oversee the non-personal data and monitor such data trust infrastructures.

The difference between personal and non-personal data also lies in the nature of its usage. It is assumed that the usage of data is static, while it is dynamic and there is a difference in the way Personal and Non-personal data are interpreted, in the attempt of regulating both Personal and Non-personal data under the same regulation may compromise the regulation of Personal data - which is the utmost concern. There is a need to look for an implementation mechanism when it comes to regulating non-personal data, concerning data fiduciaries must be very well aware of the technical and legal process. The argument behind the use of non-personal data is on the basis of public good, economic interest, and commercial competitiveness; however, the grounds for protection of Personal data in India rests on informational privacy, liberty, and autonomy of the individual.5

|

Bill Provision after JPC’s recommendation |

Recommendations |

|

Inclusion of Non-personal Data in the bill: a) Including non-personal data within the ambit of the Data Protection Bill. b) Division of Non-Personal Data in three divisions: 1) Public 2) Community 3) Personal c) The draft framework aims to empower communities and enforce right over non-personal data through the institutions of data trust, and the fiduciary duties exercised by data trustees acting in the interest of communities. |

a) Exempting anonymised data from the law may encourage companies to anonymize more. - It is a tedious process for firms to protect non-personal data along with personal data, which can affect small enterprises since they may not have a solid infrastructure to protect non-personal or anonymised data, with a lack of such required infrastructure big enterprises may not collaborate with them. - In an attempt of regulating both personal and non-personal data under the same regulation may comprise the regulation of personal data - which is the utmost concern. - The implementation mechanism should be defined when it comes to regulating non-personal data. b) The community non-personal data brings complications unlike public and private non-personal data which is distinguishable on the basis of the entity collecting it. - Insights on defining community are still lacking in the report, and must be defined by JPC. c) There must be established regulations and working standards for data trust, such as: - The infrastructure needs to be regulated in such a way that responsibility is also assigned and freedom to work is also ensured. - The relationship between data fiduciaries and data trustees seeks transparency, as data trustees are vulnerable to getting influenced by data fiduciaries. - The DPA should dedicate one of its agencies to oversee the non-personal data and monitor such data trust infrastructures. |

2) Creation of Data Protection Authority:

According to the PDPB framework, The Data Protection Authority (DPA), will enforce the Bill and ensure the privacy rights of individuals by looking into the breaches of personal and non-personal data.

The JPC mentioned the following recommendations with respect to the functioning of DPA:

- Related to the data breach notification, it should be mandatory for every data fiduciary to notify DPA within 72 hours of discovery of the breach, the reporting time frame is similar to GDPR. Following that DPA will decide upon whether Data principals are required to be informed or not depending upon the nature of the breach and its effect on data principals.

- On the structure of DPA, as per Clause 42 of PDPB’ 19, the selection committee for appointing the members of DPA is comprised of members of the executive, as per this provision the government will have a huge influence on DPA but as per recommendation by JPC, changes are made in Clause 42(2). According to DPB’ 21 the Attorney General, directors from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) and the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), to the DPA’s Selection Committee. Again the members will be nominated by the central government, so overall it did not solve the actual problem as there is still government’s intervention. Here JPC missed the opportunity of recommending an institutional design or framework. It requires a robust institutional network with central, state and zonal outreach. It must have federal characteristics to reach the grassroots level.6

- Clause 86 of the PDPB’ 19 mentioned that DPA will be bound by the orders of the central government “on questions of policy”, however, the JPC recommended - DPA is bound by the government “under all cases and not just on questions of policy” hence the phrase “on questions of policy” should be removed from Clause 86(2). Questions of policy here signify functional independence of DPA. Though the JPC has vaguely stated that DPA will be bound by the orders of the central government under all cases and not just on questions of policy. Again it failed to establish what will be the conditions where DPA will have to give up its functional independence against the government’s order, or did not define the types of “cases” under which the central government would issue an order for DPA’s compliance. This could lead to significant executive influence over business decisions like data flows and will act as a barrier.

- Further, in the case of cross-border data transfers, DPA was required to consult the union government before approving any kind of such data transfer. As per the PDPB’19 draft, sensitive personal data can be sent outside Indian territory under an “intra-group scheme or contract” approved by DPA. however, this has been familiar practice across the globe including GDPR ie. cross-border data transfer on the basis of contracts. But the JPC has tweaked this particular provision by stating that the data transfer will not be possible even under the approved contracts and intra-group schemes if the data transfer “is against the Public policy or State policy”.7 This provision humiliates the presence of the DPA, the DPA is an entrusted regulatory authority and it should have the power to decide the standards of data transfer. Government interference in data transfer even after ensuring data principal’s privacy is also a hindrance to ease of doing business. Additionally, seeking case-by-case approval will cause delays which can lead to business disruption. The metric to validate qualities of data against public or state policy is not yet defined, which leads to the questioning of the functional implementation of the particular clause. Further, there is no clarity on how administrative implementation of assessing data would take place after requesting a data transfer by any data fiduciary, where to make the request of data transfer, who will entertain the request, how much will be the minimum approval time required, is there any default approval provision if there is no reply from the authority etc. and how the whole procedure will be carried out.

- There are chances of jurisdictional overlap of DPA with other compliance bodies such as Competition Commission India (CCI), Security and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) etc. The DPB’ 21 stated that if there are any such overlaps, DPA needs to consult its respective authority before making any explicit decision, further DPA and other regulatory bodies can also enter a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU).

- The JPC’s recommendation mandates consent requirements before data processing, it provides an exemption for very minimal cases of health emergencies on ‘reasonable grounds’ again these ‘reasonable grounds’ are not being mentioned in the bill rather DPA has the authority to decide reasonable purposes for data processing. Here the bill seeks overdependence on the Data Protection Authority, instead of mentioning ‘reasonable grounds’ in the bill itself. The bill should provide a gist to data fiduciaries regarding the cases of exemption.

|

Bill Provision after JPC’s recommendation |

Recommendations |

|

Creation of Data Protection Authority: a) As per clause 42 of PDPB’ 19, the selection committee for appointing the members of DPA is comprised of members of the executive, After JPC's recommendations the selection committee would include the Attorney General, directors from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) and the Indian Institute of Management (IIM). b) Clause 84 of the PDPB’ 19 mentions that DPA will be bound by the orders of the central government “on questions of policy”, but the JPC recommended - DPA will be bound by the government “under all cases and not just on questions of policy” hence the phrase “on questions of policy” should be removed from Clause 86(2). Questions of policy here signify functional independence of DPA. c) In the case of cross-border data transfers, DPA is required to consult the union government before permitting any kind of such data transfer. As per the PDPB’19, sensitive personal data can be sent outside the Indian territory under an intra-group scheme or contract approved by DPA. The JPC has tweaked this particular provision by stating that the data transfer will not be possible even under the approved contracts and intra-group schemes if the data transfer “is against the public policy or state policy”. d) The JPC mandated consent requirements before data processing, but it provides an exemption for very minimal cases of health emergencies on ‘reasonable grounds', which will be decided by the DPA. |

a) The Power to nominate the members of DPA even after the recommendation by JPC rests with the government as IITs, IIMs are government’s agency, this does not solve the fundamental problem of government intervention. - By opening it only IITs and IIMs, again fails to make it fully democratic, rather than restricting to IITs, and IIMs the government should find right experts from the domain. - JPC missed the opportunity of recommending an institutional design or framework. It requires a robust institutional network with central, state and zonal outreach. It must have federal characteristics to reach the grassroots level. b) The JPC has vaguely stated that DPA will be bound by the orders of the central government under all cases and not just on questions of policy. - The JPC shall establish what will be the conditions where DPA will have to give up its functional independence against the government’s order, or did not define the types of “cases” under which the central government would issue an order for DPA’s compliance. This could lead to significant executive influence over business decisions like data flows and will act as a barrier. c) This provision humiliates the presence of the DPA, the DPA is an entrusted regulatory authority and it should have the power to decide the standards of data transfer. - Seeking case-by-case approval will cause delays which can lead to business disruption. The metric to validate qualities of data against public or state policy is not yet defined, which leads to the questioning of the functional implementation of the particular clause. - There is no clarity on how administrative implementation of assessing data would take place after requesting a data transfer by any data fiduciary, where to make the request of data transfer, who will entertain the request, how much will be the minimum approval time required, is there any default approval provision if there is no reply from the authority etc. and how the whole procedure will be carried out. d) Reasonable ground is not being mentioned in the bill, such reasonable purposes for data processing will be decided by the DPA. - The bill seeks overdependence on the Data Protection Authority, rather it could have mentioned the ‘reasonable grounds’. It could have also given a gist to data fiduciaries regarding the cases of exemption. |

3) Surveillance Recommendations by JPC:

In India, surveillance legislation does not have any parliamentary or judicial accountability for any act of surveillance.8 However, there is no specific law governing surveillance in India, but there are certain indirect laws through which the government derives power to conduct surveillance on citizens. The Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 is used for communication surveillance while Section 69 of the IT Act, 2000 is used for electronic surveillance which deals with the individual’s activity on the internet.9 The roots of existing legal procedure for surveillance is in the Supreme court’s intervention in 1996, which responded to the PIL filed by Public Union for Civil Liberties. The SC stated certain guidelines to be followed by the government, these guidelines were inculcated in IT Act, 2000. In 2012, the government undertook an exercise in order to find the lacunae in the existing framework. There was a commission deployed to perform this exercise under the chairmanship of Justice A P Shah. The commission mentioned that the current framework did not suggest the scale of information to be collected, it also mentioned certain clashing points between the Telegraph act and the IT act which leads to the creation of gray area. In the absence of a Data Protection regime, it cannot be expected, which type of data would fall under a person’s right to privacy and what doesn’t, this ends up giving the government a free hand to collect all kinds of data.

The Justice S.K. committee emphasized on surveillance to be included in the bill and the committee then had also made provisions in 2018. The JPC’s recommendation reads, as per Section 35 - any agency under the Centre is exempt from all or any provisions of the law in the name of “sovereignty”, “friendly relations with foreign states” and “security of the state”. However, the JPC establishes a reason for the government to exempt any agency which processes data in the name of national security. Here the term national security is absolute, in that sense, anything can be inculcated within the ambit of national security. There is a strong need to establish basic parameters for an issue to get qualified as a national security issue. There is a need to establish a process that can rationalise the granting of exemptions to the government, and this procedure of granting exemptions should be made public over a period of time. Interestingly, the JPC laid an important safeguard ie. while exempting any agency, the government needs to prescribe a procedure for oversight that must be just, fair, reasonable, and proportionate. Any agency cannot simply process personal data in the name of national security but they are bound to justify the underlying reason behind any such processing of data. On the aspect of surveillance maximum dissent notes have been filed by the opposition in the parliament, even after providing a crucial safeguard, JPC equips the government to establish a procedure of authorization instead, the committee could have laid down the guidelines.

At any given point in time, the government is going to be significant data fiduciary, as it collects a huge data, and mass surveillance projects are prominent tools used by the government to maintain national security against any possible terrorist threat by policing people, projects such as the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems (CCTNS) - a project under the Indian government for creating a comprehensive and integrated system for effective policing through e-Governance, Central Monitoring System (CMS), The National Intelligence Grid (NATGRID) - the integrated intelligence master database structure for counter-terrorism purpose connecting databases of various core security agencies under Government of India. However, these projects are extremely important for State’s security but are also required to be undertaken by surveillance regulation to mitigate any possible misuse of citizens' privacy. The JPC needs to establish a midway between the protection of “sovereignty” and ensuring the privacy of citizens.

|

Bill Provision after JPC’s recommendation |

Recommendations |

|

Surveillance: - The Draft bill of 2021 formed with the JPC’s recommendation reads, as per Section 35 - any agency under the Centre is exempt from all or any provisions of the law in the name of “sovereignty”, “friendly relations with foreign states”' and “security of the state”. - The JPC establishes a reason for the government to exempt any agency which processes data in the name of national security. |

- The term national security is absolute, in that sense, anything can be inculcated within the ambit of national security. There is a strong need to establish basic parameters for an issue to get qualified as a national security issue. There is a need to establish a process that can rationalise the granting of exemptions to the government, and this procedure of granting exemptions should be made public over a period of time. - The JPC equips the government to establish a procedure of authorization instead, the committee could have laid down the guidelines. - Mass surveillance projects are prominent tools used by the government to maintain national security against any possible terrorist threat by policing people. The surveillance projects are extremely important for state security - though are required to be undertaken by surveillance regulation to mitigate any possible misuse of an individual’s privacy. The JPC needs to establish a midway between the protection of “sovereignty” and ensuring the privacy of citizens. |

4) Social Media Intermediaries:

Social media platforms are a vital part of digitisation, as a lot of data flows vertically (from user to authority and vice-versa), and horizontally (among users). The JPC in its report stated that the Social media platforms are designated as social media intermediaries in the Information Technology (IT) Act and the act is not able to regulate the social media platforms adequately, further it said that the current bill is about data protection while social media falls on a different tangent, which needs special attention. Though it recommended several changes to social media regulation, such as:

a) The IT act refers to social media as intermediaries, but the committee points out that the social media platforms should be designated as publishers as they act as the publisher of the content, and they have full control over the published content of their respective platforms.

b) Once the application of verification is submitted with the required documents, the social media intermediary must verify the account.

c) No social media platform shall be allowed to operate in India unless the parent company handling the platform sets up a domestic office in India.

d) Establish a statutory body - media regulatory authority, parallel to the Press Council of India (PCI), regulating the content on all the social media platforms including online, print or otherwise.

The new bill should not treat social media platforms as publishers. If the recommendations by JPC of treating social media intermediaries as platforms are retained then it can lead to conflict in the interpretation of their liability under the IT Act.10

The definition of social media platforms under Clause 3(44) reads as: “social media platform means a platform that primarily or solely enables online interaction between two or more users and allows them to create, upxload, share, disseminate, modify or access information using its services”.11 There are certain changes with respect to Clause 26, which uses the concept of significant data fiduciary - as per Section 26 of PDPB, any data fiduciary processing personal data or sensitive personal data beyond the threshold limit decided by DPA will be labeled as significant data fiduciary. The bill kept an open end for the central government to intervene, the government could notify any social media intermediary as a significant data fiduciary if their “actions” are likely to have an impact on electoral democracy. There are varied social media platforms with numerous users, social media platforms have solid power to influence people. However, there was no mechanism established, either by DPA or the government to assess the impact of any particular social media on electoral democracy, sovereignty, the integrity of India, and public order. The bill only mentions the “actions” of social media intermediaries but it did not provide any clearance on what type of “actions”, not having a proper mechanism established to measure the impact of social media can give the government an excuse to decide upon every action independently. The number of users is the strength of any social media platform, if it is going to be one of the criteria to get qualified as significant data fiduciary then almost all the major social media platforms will be tagged as significant data fiduciary. Additionally, social media intermediary becomes a significant data fiduciary (SDF) then it has to get registered with DPA, while its qualification of becoming SDF is decided by the central government, this can lead to other political biases.

Clause 27 of the required significant data fiduciaries to undertake data protection impact assessment. The additional obligations included the registration to DPA, mandatory appointment of a Data protection Officer (DPO) by the data fiduciary, and compliance with the increasing power of DPA on the significant data fiduciary (Clause 30).

Social media intermediaries, as per Clauses 28(3) and 28(4) of the bill were supposed introduce a feature of voluntary verification of accounts by users so that the verified account will be identifiable with a visible mark, though the provision of self-verification is stated under Rule 4(7) of IT Act of 2021.12 The self-verification feature will create authenticity in a social media interaction, which would eventually create trust among users by self-verification. In the self-verification process largely data fiduciary provides an option to self-verify the account using an Aadhar card or any government ID. Recently, Koo, a micro-blogging platform allowed Indian users to voluntarily self-verify using an Aadhar card (a mandatory requirement). Koo became the first social media platform to comply with Rule 4(7) of IT Act’21. There are several concerns when self-verification features come into the scenario:

- Even though the IT act denotes that information received shall only be used for verification purposes, there is no data protection regime to ensure this. The new bill strongly needs to ensure that the verification information cannot be used as additional data points by social media platforms.

- The verification will be based on the user’s choice but if such provisions are mandated then the government can easily track critics which can severely affect minorities, whistleblowers and victims of any sort of assault, as they fall back on anonymous identities on social media websites to express their opinions.

|

Bill Provision after JPC’s recommendation |

Recommendations |

|

Social Media Intermediaries: a) The JPC Stated that current Draft Data Protection bill’ 21 is about data protection while social media falls on a different tangent, which needs special attention. b) The JPC recommends that social media platforms should be referred to as Publishers rather than intermediary. However, the Draft bill, 2021 doesn't mention about this change c) As per Section 26 of PDPB, any data fiduciary processing personal data or sensitive personal data beyond the threshold limits decided by DPA will be labeled as significant data fiduciary. The central government can notify any social media intermediary as a significant data fiduciary if their “actions” are likely to have an impact on electoral democracy. |

a) No recommendation. b) If the recommendations by JPC of treating social media intermediaries as platforms are retained then it can lead to conflict in the interpretation of their liability under the IT Act. c) Notification of social media intermediaries should be as per a procedure and thresholds should be clarified. - There is no mechanism yet established by either DPA or the government to assess the impact of any particular social media on electoral democracy, sovereignty, the integrity of India, and public order. - The bill only mentions the “actions” of social media intermediaries, but it does not provide any clearance on what type of “actions”, such clearance must be established by the JPC. Again it gives space for the government's intervention. |

5) No Recommendations on Web 3.0:

The global internet regime is gradually making a shift towards third generation internet ie. web 3.0. It is a decentralized network which operates on a blockchain ledger technology where an enormous amount of data is generated. It is complicated to understand the working of data flow in the web 3.0 ecosystem. Neither the PDPB nor the JPC has tried to include the concept of data protection in the web 3.0 ecosystem. Therefore, how data protection in web 3.0 will be different from web 2.0 is still a question.

Data will be interlinked in web 3.0 in a decentralised manner compared to web 2.0 where data is centralised and one entity controls it ie. Data Fiduciary. Web 3.0 allows data processing with clever human intelligence by the deployment of AI systems that can run advanced programs to help the users.

Web 3.0 is focused on making personal information private by default. It builds on the idea of giving data ownership to users. Web 3.0 enables individuals to decide how they want their data to be stored and collected, and how they want it to monetise.13 However, data protection bill regulates data flow, providing citizens maximum ownership over their data, but Web 3.0 does not require legitimisation in its approach to decentralisation. If it is not legitimized then it limits the scope to question data fiduciaries in cases where they don’t comply with the fundamental nature of blockchain, however, the new bill can play a crucial role in legitimising firm’s responsibility running on blockchain and make them compliant.

Web 3.0 has the capacity to contribute over 1 trillion USD to the Indian GDP by 2031. India has the second largest internet user in the world, with 845 million internet and 518 million social media users in 2021.14 By 2040 it is expected that a total number of internet users in India would cross 1.53 billion. India has the opportunity to lead the global policy framework for Web 3.0. Designing this policy from only a “control perspective” might lead technologies into the dark web or push entrepreneurs and capital to other global markets. In the beginning of webade (Web 3.0 decade), India can adopt the approach of positive liberty by defining the no go areas very well. Through this the government can make it clear from a legal perspective about what it allows and what it does not encourage from the web 3.0 ecosystem, intervening in the middle of the internet revolution may disturb the enterprises in shaping its environment to compete globally, Indian entrepreneurs also seek for policy and regulatory clarity on web 3.0 infrastructure, for instance, ambiguities with the scope of crypto currency in India.

The new bill should make clarifications regarding the definition of personal - non-personal - mixed data sets even in the Web 3.0 domain. Will it be the same as the web 2.0? or will there be extra obligations on agents who are involved in data flow? The Data Protection legislation can act as a check on the validity of the Web 3.0 ecosystem, as it claims to be decentralised and disseminates data among its users, in this way the new Data Protection Bill can play a complementary role rather than being a hurdle in the internet revolution.

Progression of Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) technology is taking place to shape the 3-D internet world and digital social interaction - also termed as Metaverse. The concept of Non Fungible Tokens (NFT) plays a prominent role in Metaverse. Crucial legal questions around privacy, safety, and security arise in Metaverse, which needs intense deliberations. If data is not regulated, online challenges like snooping, data breaches, and harassment (cybercrime) can easily get amplified. Data is the basis for the creation of the Metaverse, in that case virtual interaction leads to greater sharing of data, this may lead to greater concerns over data breach and threats on how the company collects and handles personal data of people, such prominent concerns must be addressed in the upcoming bill.

The data governance in Metaverse needs to be precisely defined by the state. The online safety, privacy hygiene, and the digital well-being are essential for the people to engage in the online communities. With the expansion of metaverse we are experiencing advanced borderless socio-digital interactions. When it comes to data regulation, countries may not be able to do it on their own. In a borderless network countries have to make well integrated and informed data protection strategies through collaborations.

|

Bill Provision after JPC’s recommendation |

Recommendations |

|

No Recommendation on Web 3.0 or blockchain technology: a) The bill does not provide any recommendation on data protection under Web 3.0 domain. |

- The DPB '21 shall make clarifications regarding the definition of personal - non-personal - mixed data sets even in the Web 3.0 domain. - The Data Protection legislation can act as a check on the validity of the Web 3.0 ecosystem, as it claims to be decentralised and disseminates data among its users, in this way DPB can play a complementary role rather than being a hurdle in the internet revolution. - Crucial legal questions around privacy, safety, and security arise in Metaverse, which needs intense deliberations. If data is not regulated, online challenges like snooping, data breaches, and harassment (cybercrime) can easily get amplified. Data is the basis for the creation of the Metaverse, in that case virtual interaction leads to greater sharing of data, this may lead to greater concerns over data breach and threats on how the company collects and handles personal data of people, such prominent concerns must be addressed by the DPB '21. |

6) Consent Mechanism

Consent is the crucial part of any data protection law, the JPC made it clear that no user can be legally denied service if they deny the consent form.15 However, the scope of processing non-consensual personal data has increased. Any exemption from the principles of consent mechanism can be only made after satisfying necessary conditions defined by the supreme court, which include - a legitimate purpose, a proportionality evaluation and procedural safeguards as per the right to privacy judgment, but unfortunately the Draft Data Protection Bill (DPB), 2021 failed to insert such required safeguards.1616 In PDPB 2019, such processing of personal data without consent was only allowed when it was “necessary”, while the JPC included an additional term - “reasonably expected”, this broadens the scope of processing personal data without consent. Clause 12 of PDPB, stated processing of personal data without consent in necessary conditions - here, the grounds for processing of personal data under certain areas were not clarified, while JPC differed its stand and recommended processing of personal data without consent under clause 12 within the “purpose limitation” framework of the PDP Bill, 2019. As per Clause 8(3), PDP Bill’ 19, where a data fiduciary finds that the personal data of the data principal which has been disclosed to another data fiduciary or processor is not complete, accurate or updated, it should notify such individual or entity of the same. The JPC suggested that a provision should be added, exempting its application in cases where processing may be carried out with respect to Clause 12, PDPB’19. The reasons given by the JPC are, such conditions may not be in sync with the provision of Clause 12 and can affect the smooth functioning of the government agencie’s processing of personal data.17 As Clause 12 deals with non-consensual processing of personal data, such processing of personal data should not be hidden from data principals, a notification to data principal is still necessary even under Clause 12 and should be more deliberate.

The DPB 2021 added quasi-judicial authorities as entities that can process personal data without consent. In Clause 13, the JPC has given the recommendation to provide an exemption to employers to process employees' data without consent only for employment purposes, but ‘only if it is necessary or can reasonably be expected by the data principal’. The underlying condition is vital to prevent instances of data misuse by the employer; including sharing of this data with other entities for anti-competitive purposes. Further, Clause 14 from PDPB’ 19 was retained in the draft bill of 2021, that exempted user consent for collecting data for the purpose of credit scoring and search engines. Here the only safeguard added by the JPC was to state if the data collection is for the legitimate interest of the data principal.18

Consent is at the substratum of any Data Protection Regime, and it cannot be compromised. The bill made various exemptions based on phrases like legitimate interest, and a necessary condition further these terms are vaguely defined in the bill when it comes to the consent mechanism.

-

Bill Provision after JPC’s recommendation

Recommendations

Consent Mechanism:

a) The JPC’s recommendation made it clear that no user can be legally denied service if they deny the consent form.

b) In PDPB 2019, non-consensual processing of personal data without consent was only allowed when it was "necessary", while DPB 21, allows such processing whenever it can be "reasonably expected".

c) Clause 12 of PDPB, which signifies processing of personal data without consent in necessary conditions.

d) Clause 8(3), PDP Bill, 2019, finds, whenever a data fiduciary finds that the personal data of the data principal which has been disclosed to

another data fiduciary or processor is not complete, accurate or updated, it should notify such individuals or entities of the same. The JPC suggested that a provision should be added, exempting its application in cases where processing may be carried out with

respect to clause 12, PDPB’19. The reasons given by the JPC are that such conditions may not be in sync with the provision of clause 12 and

can affect the smooth functioning of the government agencies’ processing of personal data.

e) Clause 14 from PDPB’ 19 has been retained in the draft bill of 2021, exempting user consent for collecting data for the purpose of credit scoring and search engines. The only safeguard added by the JPC was to state if the data collection is for the "legitimate interest" of the data principal.

a) No recommendation

b) Any exemption from the principles of consent mechanism can be only

made after satisfying necessary conditions defined by the supreme court,

which include - a legitimate purpose, a proportionality evaluation and procedural

safeguards as per the right to privacy judgment.

- Terms like "reasonably expected" and "necessary" shall be defined

c) The grounds for processing of personal data under certain areas is not clarified,

The JPC must clarify its stand.

d) As clause 12 deals with non-consensual processing of personal data,

such processing of personal data should not be hidden from data principals,

a notification to data principal is still necessary even under clause 12 and should be more deliberate

e) Consent is at the substratum of any Data Protection Regime, and it cannot be compromised.

The DPB '21 phrases like "legitimate interest", and a "necessary condition" shall be well defined.

7) Data Transfer, Localisation and Portability:

- The Indian data protection bill provided the strictest regulation when it comes to Data localisation and portability.

- The draft showcase a three-tier structure of data transfer:

a) Personal Data

b) Sensitive Data

c) Critical Personal Data

This structure signifies, no restriction for data transfer applies to personal data. When it comes to sensitive data, the bill mandates a copy of sensitive data to be stored locally else it cannot be stored outside India. However, Critical personal Data is a type of data set which will be defined by the government, and it must be stored locally and never outside of India. The critical personal data is still not defined clearly, which may create ‘compliance uncertainty’ for business entities. Further, the stringent requirements of data localisation can impact industries adversely. This can also impact India's trade position, and commercial interest with the EU, USA, and the UK, it will further complicate the data transfer agreements.

The Data Protection Authority is bound to consult the government in the case of sensitive personal data transfer, the concept of data localisation is strict yet free for the government to intervene, the fresh language of draft bill 2021, signifies the reduction in autonomy of Data Protection Authority (DPA). Further the JPC has missed the opportunity to engage in global data flow arrangement such as Data partnership, Data for societal objectives, Data philanthropy which can be enhanced using bilateral or multilateral treaties. There are various instruments such as “adequacy or equivalence determination” which is a unilateral recognition certifying that the data protection regime of another country meets certain privacy requirements and so data can be transferred unhindered to this country, “Pre approved contractual safeguards to binding corporate rules or standard expectations like legitimate interest, consent of data principal, public interest”, “Standard contractual Clauses” are regulations that provide for data transfers to third-parties located in different countries.19 Using such instruments, data flow can be made possible overseas with countries having data protection laws, without impeding privacy. This can create robust infrastructure with collaborative efforts, heading towards a midway between extreme to minimal data localisation.

Moreover, the JPC did not mention how Indian data protection can incorporate the interoperability aspect and harmonise with the global data protection ecosystem. The technologies like cloud computing help to isolate or segregate sensitive data during processing by ensuring its encryption during the process, there are several technologies that can be applied during the life cycle of data to ensure its privacy but the JPC has not tried to involve any scope of deploying such technologies in its recommendations. Companies will have to bear the extra expense of both data transfer and localisation. It is estimated that the Indian economy can lose up to 0.7-1.7% of its GDP due to stringent norms of data localisation.20 However, Section 39 of the bill supported small entities engaged in non-automated or manual processing of data from the complexities of data localisation. But the term ‘automated’ is vaguely defined in the bill, entities not using computers for processing data are only considered under manual processing. Here, the DPA was given the responsibility to set standards. In the GDPR, SMEs are exempted from appointing Data Protection Officers (DPOs) on the basis of personal requirements.

Data Portability:

Data Portability is another crucial aspect of the bill. The draft bill of 2021 had a provision of data portability under Clause 19, which allows consumers to port concluded data from one online service provider to another. The Data Portability rights allow data principals to obtain and resume their personal data for their own purposes, it permits them to move, copy, or transfer their personal data from data fiduciary to another in a safe and secure way, without affecting its usability.21

The JPC recommended that all the data fiduciaries dealing with personal data must establish means by which the rights of data principal can be transferred. It may get difficult for small enterprises to comply with the data portability principle and create injustice for small data fiduciaries who are required to draw conclusions by processing user data (concluded data), which can help firms to upgrade their product or services, compared to large firms with solid infrastructure which may derive substantial value from personal data. Therefore, such regulation should be imposed on the basis of certain parameters rather than making universal implementation. These parameters could be differentiated market size, operations, and the number of users the firm engages, etc.

However, it differs from other data protection regimes like GDPR and Singapore’s data protection law, where companies can deny the transfer of data if it is affecting the company’s competitiveness. In such countries as it is concluded data, companies use it for providing better-targeted services, which is part of the business. On the side of the technical feasibility exception, the GDPR specifies that the firms need to maintain minimum interoperability, allowing users to collect and transfer their data between service providers. While the JPC has left this aspect of technical feasibility up to the interpretation of fiduciaries but in a manner specified through regulation.22 The existing evidence from regimes like the GDPR shows that firms are spending about $1.3 million - $1.8 million annually complying with data protection laws. Further portability is recognised as one of the most complex corporate obligations that includes cost for development, authentication, processing and maintenance of data. It is even more complex for digital enterprises that undertake business in borderless cyberspace.

- Data portability Regulation: Comparative Analysis with GDPR

Definition of personal data under GDPR includes ‘directly or indirectly identifiable information’ on name, identity number, location data, an online identifier - or natural person. The DPB’ 21 includes personal data as directly or indirectly identifiable including “any inference drawn from such data for the purpose of profiling”, implying portability for information provided voluntarily. However, the bill nowhere specifies generated, obtained or inferred data-keeping its scope open to interpretation .

The GDPR specifically exempted inferred data or derived data from the purview of portability even when it is related to personal data, as such datasets are produced by data fiduciaries over a period of time which can be used for anticipation and hence it is a part of business competitiveness and has economic relevance. Alongside, the GDPR also exempts trade secrets and information whose portability is technically unfeasible from the compulsion of data portability. Similar features were replicated in PDPB’ 19, however the committee recommended that trade secrets cannot be the ground for denying data portability and should only be denied in case of technical feasibility.

The EU grants protection to information that has commercial value and economic significance. However, JPC suggested removing exceptions like GDPR stating high chances of manipulation . By removing this exception, enterprises will be more accountable to share data, which may negatively impact competition and innovation. Such policies require strong clarification on the nature of their applicability which includes complete information on porting requirements. Additionally, the JPC failed to state the implementation guidelines on how the data portability will work, if the data fiduciary must seek the DPA’s clearance on every data portability request.

work, if the data fiduciary must seek the DPA’s clearance on every data portability request.

|

Bill Provision after JPC’s recommendation |

Recommendations |

|

Data Transfer, Localisation and Portability: a) The draft showcase a three-tier structure of data transfer: - Personal Data - Sensitive Data - Critical Personal Data - Critical personal Data is a type of data set which will be defined by the government, and it must be stored locally and never outside of India. The critical personal data is still not defined clearly in the bill. b) The Data Protection Authority is bound to consult the government in the case of sensitive personal data transfer, the concept of data localisation is strict yet free for the government to intervene, after JPC’s recommendations. c) The JPC did not mention how Indian data protection law can incorporate the interoperability aspect and harmonise with the global data protection ecosystem. d) Section 39 of the bill supported small entities engaged in non-automated or manual processing of data from the complexities of data localisation. e) The DPB with committee recommendations states that all the data fiduciaries dealing with personal data must establish means by which the rights of data principal can be transferred. |

a) Due to lack of understanding of critical personal data, may create ‘compliance uncertainty’ for business entities. Not defining "Critical Personal Data" may give open end to the government to interpret any data as Critical Personal Data. There shall be certain parameters set for any data to get qualified as the Critical Personal Data. b) This particular provision compromises with the functional independence of the Data Protection Authority due to government intervention, and signifies the reduction in autonomy of Data Protection Authority (DPA). c) The technologies like cloud computing help to isolate or segregate sensitive data during processing by ensuring its encryption during the process, there are several technologies that can be applied during the life cycle of data to ensure its privacy but the JPC shall try to involve scope of deploying such technologies in its recommendations. d) The term ‘Automated’ is vaguely defined in the bill, entities not using computers for processing data are only considered under manual processing. Here, the DPA has been given the responsibility to set standards. The JPC, shall clearly define the term 'Automated'. e) It may get difficult for small enterprises to comply with the data portability principle and create injustice for small data fiduciaries who are required to draw conclusions by processing user data (concluded data), which can help firms to upgrade their product or services, compared to large firms with solid infrastructure which may derive substantial value from personal data. Therefore, such regulation should be imposed on the basis of certain parameters rather than making universal implementation. These parameters could be differentiated market size, operations, and the number of users the firm engages, etc. Differential Point: GDPR and Singapore’s data protection law, where companies can deny the transfer of data if it is affecting the company’s competitiveness. In such countries as it is concluded data, companies use it for providing better-targeted services, which is part of the business. |

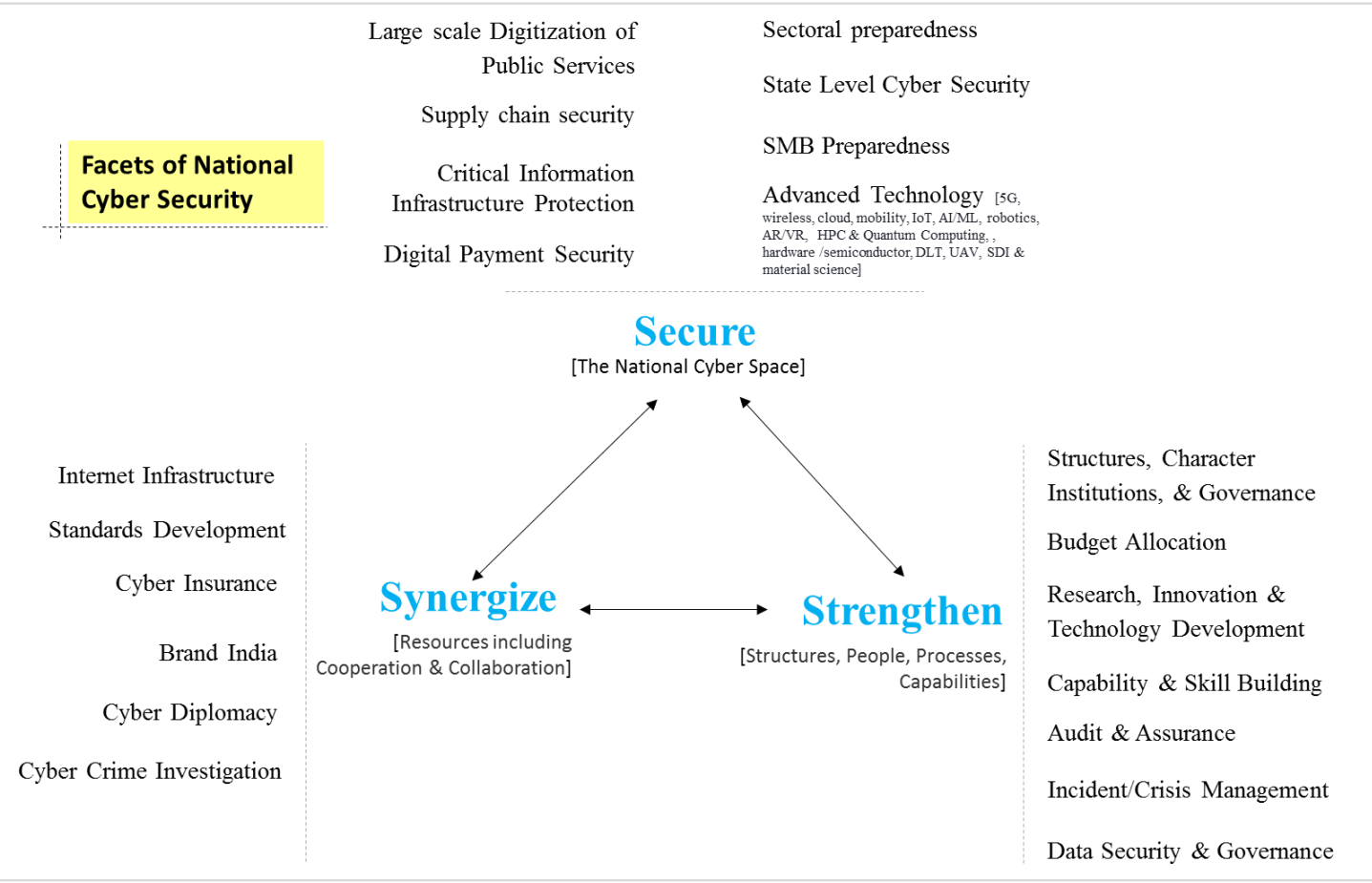

8. Cyber Security and Data Protection Bill 2021:

India witnessed a total of 11,58,208 cyber security incidents in 2020-21, such attacks increased to 12,13,784 by October’21. Among these, about 87,050 were against government organisations in the last two years. These are concerning figures when it comes to cyber security.23 The nodal agency, the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In) is established under IT Act, 2013, the agency is mandated to monitor and respond to cyber security incidents. The Government has also set up the National Cyber Crime Reporting Portal "To deal with cybercrimes in a coordinated & comprehensive manner, [and] … to enable citizens to report complaints pertaining to all types of cybercrimes with special focus on cyber crimes against women and children," the government said. While India doesn’t have a dedicated cyber security law, the IT Act, 2000 deals with cybersecurity and related cybercrimes. Some related cybersecurity provisions are also dealt with using Indian Penal Code (IPC). However, stringent cyber laws are still lacking in India, making it difficult to penalise the offenders, for instance in IT Act, 2000 under Section 66F only the act of cyber terrerisom is punishable with life imprisonment, rest all acts of crimes are punishable for 3-7 years under Section 66 of the act. If there is a slender hacking without the purpose of phishing, money laundering, email frauds etc. then it does not include imprisonment. This provides a window to escape to the offenders by exploiting lacuna.

Cyber Security is never limited to the physical borders of the countries, when cyber offenses cross the boundaries of any nation-state with a vested interest against another state, then it is termed cyber warfare - it is a situation where computer technology is used to intentionally disrupt the information system of any state for military purposes. Recently, the Chinese hacker group known as Stone Panda has identified gaps and vulnerabilities in the IT infrastructure and supply chain of Bharat Biotech and the Serum institute of India. One in four Indian organisations had suffered a ransomware attack in 2021, that is above the global average of 21%.24

Figure 3: Facets of National CyberSecurity

Source: Data Security Council of India

This can contextualise the data protection framework from a cybersecurity perspective for required protection of data.

Though, there is a fundamental act regulating internet activity over digital space i.e., the Information Technology Act (IT), 2000. Cyber Security is defined under Section (2) (b) - protecting information, equipment devices computer, computer resource, communication device and information stored therein from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification or destruction25. However, the IT Act even after the amendment in 2008, still does not define the term cybercrime, thereby making it difficult to penalise an offender. But the IPC and the IT Act penalises a number of cyber crimes and there are several provisions in IPC and IT Act that overlap with each other.26

CERT-In issued directives related to the information security practices, procedures, prevention, response, and reporting of cyber crime incidents for Virtual Private Network (VPN) providers and other service providers on 28th April’22.27 VPN service providers are supposed to store users’ data for five years even after the client has stopped availing of the service. Implementing such a policy in absence of a data protection law could actually backfire because of the ever-looming possibility of cyberattacks or leakages of the private consumer data stored by the VPN providers for a long period of time. Strong cybersecurity is the prerequisite for data privacy. Further companies storing users’ data for five years and sharing it with the government on legal request (as required by the CERT-In Directives) can lead to data breaches or malicious attacks which can make an individual's privacy vulnerable.

Moreover, the CERT-In orders are opposing to the provisions of the Data Protection Bill. As per Section 18(1)(d) of the bill, data principals have the right to erase their personal data that no longer serves the purpose for which it was collected. The Bill restricted retention of personal data after its purpose is fulfilled, in this case as VPN companies have no purpose to process users’ personal data, so it should automatically not collect personal data or if collected then should not store it.

|

Bill Provision after JPC’s recommendation |

Recommendations |

|

CyberSecurity and DPB'21: a) CERT-In issued directives related to the information security practices, procedures, prevention, response, and reporting of cyber crime incidents for Virtual Private Network (VPN) providers and other service providers on 28th April’22 - VPN service providers are supposed to store users’ data for five years even after the client has stopped availing of the service. |

a) Implementing such a policy in absence of a data protection law could actually backfire because of the ever looming possibility of cyberattacks or leakages of the private consumer data stored by the VPN providers for a long period of time. Strong cybersecurity is the prerequisite for data privacy. Further companies storing users’ data for five years and sharing it with the government on legal request (as required by the CERT-In Directives) can lead to data breaches or malicious attacks which can make an individual's privacy vulnerable. The CERT-In orders are contrasting to the provisions of the Data Protection Bill. As per section 18(1)(d) of the bill, Data principals have the right to erase their personal data that no longer serves the purpose for which it was collected. The Bill restricts retention of personal data after its purpose is fulfilled, in this case as VPN companies have no purpose to process users’ personal data, so it should automatically not collect personal data or if collected then should not store it. |

9. Right to be Forgotten:

In India, the “Right to be forgotten” was recognised by the Supreme Court of India within the ambit of the Right to privacy. The Delhi High Court in its recent judgment of Jorawer Singh Mundy vs. The Union of India held that Right to be Forgotten is the tangent of Right to Privacy. Clause 20(1) and Clause 20(2) of PDPB gave the right to the data principal to prevent or restrict the continuing disclosure of his or her personal data. The JPC noted that the word “disclosure” alone cannot serve the purpose, as data can be used in varied forms and can also be processed without disclosing it. Therefore, the committee added the term ‘processing’ to the clause.28 Earlier companies were only restricted to store and publish personal data but now they are also bound to process personal data, this provision should seek balance with Rights of the company.

As per Section 18(1)(d), data principals have the right to erase their personal data that no longer serves the purpose for which it was collected, to which the JPC questioned why the provision is not extended to erase all personal data, it creates information asymmetry for data principals, if the information is still relevant or not for data fiduciaries, as they are bound to rely on the information provided by data fiduciaries.

The Bill restricted retention of personal data after its use or after its purpose getting fulfilled. The data fiduciaries are bound to delete all the personal data collected after its intended usage. This provision clashes with Section 18(1)(d), as per restriction to retention of personal data, the data is going to get deleted by data fiduciaries after its purpose is fulfilled, then how data principal’s request of erasure of personal data is applicable if it has no longer purpose to be stored. Such data by default will be deleted under restriction to retention. The JPC observed that Section 18(1)(d) leads to many ambiguities, it suggested DPA to frame regulation over the implementation of the Right to be forgotten provision - in order to protect the privacy of individuals, DPA should make regulations by keeping legal obligations in purview, ensure rights of the data principles, technical feasibility of data fiduciaries, and taking interest of the government into account. However, the Right to be forgotten of one party also clashes with the Right to get information for another party, privileged users might want to take down certain information from the server using forgotten rights. The company’s compliance cost may get increased, adhering to this feature due to complex bureaucratic procedures, the intervention of DPA and its direction shall make this process easy for data fiduciaries along with data principals.

|

Bill Provision after JPC’s recommendation |

Recommendations |

|

Right to be Forgotten: a) The JPC observed that in terms of Right to be forgotten the term ‘processing’ needs to be explicitly defined, earlier companies were only restricted to storing and publishing personal data but now entities are also bound to process personal data. b) The bill puts restrictions on retention of personal data after its use or after its purpose getting fulfilled. The data fiduciaries are bound to delete all the personal data collected after its intended usage. c) The JPC observed that section 18(1)(d) leads to many ambiguities, it suggested DPA to frame regulation over the implementation of the Right to be forgotten provision - in order to protect the privacy of individuals, DPA should make regulations by keeping legal obligations in purview, ensure rights of the data principles, technical feasibility of data fiduciaries, and taking interest of the government into account. |

a) This provision should balance with Rights of the company. b) This provision clashes with section 18(1)(d), as per restriction to retention of personal data, the data is going to get deleted by data fiduciaries after its purpose is fulfilled, then how data principal’s request of erasure of personal data is applicable if it has no longer purpose to be stored. Such data by default will be deleted under restriction to retention. c) No Recommendation |

Conclusion:-

The country’s first Data Protection Law has a lot of upcoming challenges. The Bill attempted to seek a balance between digital economy and data protection. By inculcating both personal and non personal data showed the traits of citizen’s privacy concerns, but at the cost of affecting commercial operations, creating a tension among privacy and competition for companies. Several administrative ambiguities are required to be addressed in the new bill for its better implementation. The implementation might witness the government's influence, if the Data Protection Authority is mandated to consult the government over various important aspects. There are several important terms which are vague and need to be defined in the upcoming version of the bill in order to mitigate the loopholes.

Endnotes:

1 Mandhani, Apoorva, and The Print. 2021. “Non-personal data, social media — what new 'data protection bill' could look like.” ThePrint. https://theprint.in/theprint-essential/non-personal-data-social-media-what-new-data-protection-bill-could-look-like/776389/.

2 . Oxford Academic. 2021. “International Data Privacy Law | They who must not be identified—distinguishing personal from non-personal data under the GDPR.” https://academic.oup.com/idpl/article/10/1/11/5802594#203090266.

3 Marda, Vidushi, and Ada-lovelace Institute. 2020. “Non-personal data: the case of the Indian Data Protection Bill, definitions and assumptions.” Ada Lovelace Institute. https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/blog/non-personal-data-indian-data-protection-bill/.

4 . Agrawal, Aditi, Guest Author, Sneha Johari, and Medianama. 2020. “#NAMA: What are data trusts? How do they work?” MediaNama. https://www.medianama.com/2020/08/223-nama-data-trusts/.

5 . Marda, Vidushi, and Ada-lovelace Institute. 2020. “Non-personal data: the case of the Indian Data Protection Bill, definitions and assumptions.” Ada Lovelace Institute. https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/blog/non-personal-data-indian-data-protection-bill/

6 . Mehta, Shefali, Karthik Venkatesh, Pranav B. Tiwari, Saksham Malik, Kazim Rizvi, and DeepStrat. 2021. “Preliminary Analysis: Report of the Joint Parliamentary Committee on the PDP Bill, 2019.” Deepstrat. https://deepstrat.in/2021/12/26/report-of-the-joint-parliamentary-committee-jpc-on-the-pdp-bill-2019/.

7 . Internet Freedom Foundation. n.d. “REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE PERSONAL DATA PROTECTION BILL, 2019.” Accessed August 4, 2022. Joint_Committee_on_the_Personal_Data_Protection_Bill_2019 - Internet Freedom Foundation.pdf

8 . ORF. 2022. “The state of surveillance in India: National security at the cost of privacy? | ORF.” Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/the-state-of-surveillance-in-india/.

9 . Vishwanath, Apurva, and Suvajit Dey. 2021. “Explained: The laws for surveillance in India, and concerns over privacy.” The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/project-pegasus-the-laws-for-surveillance-in-india-and-the-concerns-over-privacy-7417714/.

10 . The Print. 2021. “JPC report on data protection bill has loopholes & more bad news for social media companies.” ThePrint. https://theprint.in/opinion/jpc-report-on-data-protection-bill-has-loopholes-more-bad-news-for-social-media-companies/785214/.

11 . Internet Freedom Foundation. 2021. “Key Takeaways: The JPC Report and the Data Protection Bill, 2021 #SaveOurPrivacy.” Internet Freedom Foundation. https://internetfreedom.in/key-takeaways-the-jpc-report-and-the-data-protection-bill-2021-saveourprivacy-2/.

12 . Lok Sabha Bill. 2019. “THE PERSONAL DATA PROTECTION BILL, 2019.” MCA EBOOK. http://164.100.47.4/BillsTexts/LSBillTexts/Asintroduced/373_2019_LS_Eng.pdf.

13 . Forbes and Jeff Bell. n.d. “In Web 3.0, Data Ownership And Monetization Must Belong To Individuals.” Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2022/03/31/in-web-30-data-ownership-and-monetization-must-belong-to-individuals/?sh=fc0eb9d3d6b7.

14 14. Sridharan, Srinath. 2022. “Regulatory Leap: Why India must lead the Web 3.0 policy narrative.” The Financial Express. https://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/regulatory-leap-why-india-must-lead-the-web-3-0-policy-narrative/2515657/.

15 . Internet Freedom Foundation. 2021. “Key Takeaways: The JPC Report and the Data Protection Bill, 2021 #SaveOurPrivacy.” Internet Freedom Foundation. https://internetfreedom.in/key-takeaways-the-jpc-report-and-the-data-protection-bill-2021-saveourprivacy-2/.

16 . Parsheera, Smriti, and Rishab Bailey. 2018. “The Aadhaar judgement uses the right-to-privacy test in two completely different ways.” Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/896007/the-aadhaar-judgement-puts-forward-two-completely-different-tests-of-the-right-to-privacy.

17 . Vidhi Legal Policy. n.d. “Referencer on the JPC's recommendations for the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019.” Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/JPC-PDP-Referencer.pdf.

18 . Internet Freedom Foundation. 2021. “Key Takeaways: The JPC Report and the Data Protection Bill, 2021 #SaveOurPrivacy.” Internet Freedom Foundation. https://internetfreedom.in/key-takeaways-the-jpc-report-and-the-data-protection-bill-2021-saveourprivacy-2/.

19 . Meisner, Dan. 2019. “MAPPING APPROACHES TO DATA AND DATA FLOWS.” OECD. https://www.oecd.org/trade/documents/mapping-approaches-to-data-and-data-flows.pdf.

20 . Sharma, Aruna. 2021. “Personal Data Protection Bill can seed uncertainty for businesses, reduce competitiveness.” The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/policy-trends/personal-data-protection-bill-can-seed-uncertainty-for-businesses-reduce-competitiveness/articleshow/88116148.cms?from=mdr.

21 . Information Commissioner's office. n.d. “Right to data portability.” ICO. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-data-protection/guide-to-the-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/individual-rights/right-to-data-portability/.

22 . Priyanshi. 2022. “Data Portability under India's Personal Data Protection Bill and Competition law in the digital sector: Key takeaways from the GDPR.” Kluwer Competition Law Blog. http://competitionlawblog.kluwercompetitionlaw.com/2022/02/12/data-portability-under-indias-personal-data-protection-bill-and-competition-law-in-the-digital-sector-key-takeaways-from-the-gdpr/.

23 . Business Today. 2021. “87050 cyberattacks on govt organisations in two years.” Business Today. https://www.businesstoday.in/technology/news/story/87050-cyberattacks-on-govt-organisations-in-two-years-315695-2021-12-15.

24 . Ahaskar, Abhijit, and Sohini Bagchi. 2022. “Ransomware attacks triple in 2021; Maharashtra most-targeted state.” Mint. https://www.livemint.com/technology/ransomware-attacks-triple-in-2021-maharashtra-most-targeted-state-11648146349087.html.

25 . Deo, Rahul. 2014. “Offences Under IT Act, 2000 - Academike.” Lawctopus. https://www.lawctopus.com/academike/offences-act-2000/.

26 . Joseph, Vinod, and Deeya Ray. 2020. “Cyber Crimes Under The IPC And IT Act - An Uneasy Co-Existence - IT and Internet - India.” Mondaq. https://www.mondaq.com/india/it-and-internet/891738/cyber-crimes-under-the-ipc-and-it-act--an-uneasy-co-existence.

27 . Chhatrala, Shiv, and Policy Circle. 2022. “VPN guidelines must balance cyber security, privacy needs.” Policy Circle. https://www.policycircle.org/opinion/vpn-guidelines-cyber-crime/.

28 . Jaju, Amit. 2022. “How JPC recommendations on Personal Data Protection Bill compare with GDPR?” The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/security-tech/technology/how-jpc-recommendations-on-personal-data-protection-bill-compare-with-gdpr/articleshow/90722172.cms?from=mdr.

Shiv

Shiv is pursuing M.A. Public Policy programme at Christ University, Bangalore. He is a Public Policy enthusiast with a focus on Tech Policies. He is interested in analyzing policy and political developments at National and the State level. He has previously interned with the National Human Rights Commission and a range of policy think tanks. While working with Global Policy Insights he has worked on finding gaps and suggesting probable policy measures with respect to the Data Protection Bill.

Recent Articles

- James Silverman ( Founder, U&I Global) interviews Arpit Chaturvedi (Co-founder and CEO, GPI) on AGENDA 2030- DO WE WANT IT? CENTRALISATION AND THE SDG’S

- Big Tech on Section 230 – Censorship or Disregard?

- Global Policy Insights (GPI) Annual India Colloquium.

- Antitrust hearing only a beginning on accountability

- The Commonwealth: Optimising Networks & Opportunities for the 21st Century

- Population Data in the Time of a Pandemic

- The Disconnect with Ground Realities

- Models to Make Vocational Training Work in India

- Comparing Health Care Systems in England, Taiwan, and the United States

- Commonwealth In Dialogue : Academic Series

- Are we rewarding fence-sitters and free-riders by relaxing penalties on CSR law violations?

- Changing Economic Models: From Mixed Economy to Liberalization, Privatization, and Globalization in India

- Goods and Services Tax (GST) – a Seventeen Year Ordeal to a Uniform Indirect Tax Regime in India

-

Commonwealth In Dialogue: International leader Series