Comparing Health Care Systems in England, Taiwan, and the United States

Posted On Thursday, Jan. 16, 2020 by Brandon Lewis Venerable, Carmelisa Jurene Morales under Governance Policy

Introduction

Access to comprehensive health care services is important in maintaining health, preventing disease and achieving health equity for the most vulnerable of populations. Barriers to health services can include, but are not limited to, cost of care, insurance coverage, location of services, health governance and resources (Healthy People 2020, n.d). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines universal health coverage (UHC) as “all people and communities can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship”. To assess universal health coverage plans, WHO uses the following criteria: equity in access, quality, and cost of health services (“What is health financing for universal coverage?”, n.d.). Some argue that true universal coverage would bankrupt the economy and others fail to account for the immense level of cooperation it takes from multiple stakeholders. The following report will provide a comparative analysis of the health care systems of England and Taiwan, two countries that provide UHC, and the United States (US), a country that does not provide UHC. This report will also discuss the democratic structure of these countries and emerging trends that can better inform policies and political strategies related to health coverage.

Democratic Landscape

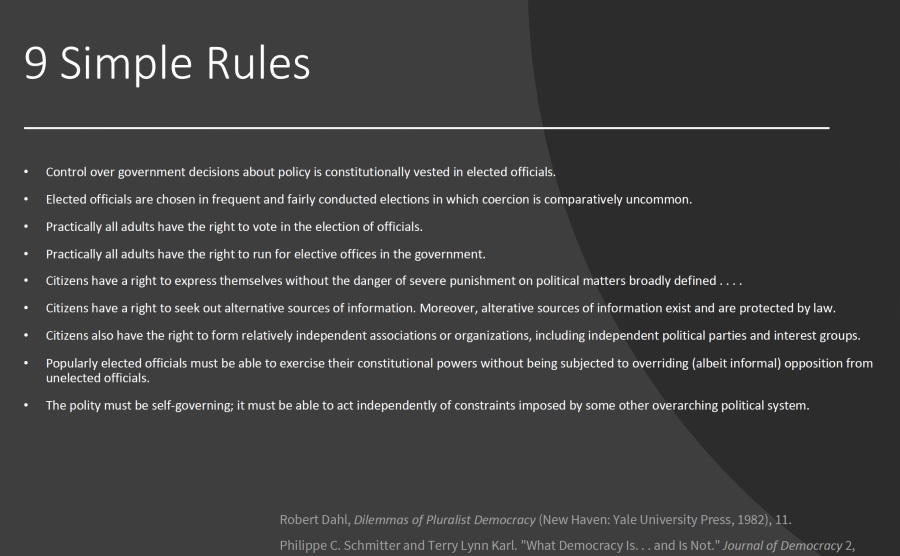

Evaluating the democratic context of each country is critical to understanding the similarities and differences in their health care systems. This section uses the democratic evaluation criteria developed by Robert Dahl (1982), Philippe C. Schmitter, and Terry L. Karl (1991) to discuss the government structure and civic engagement in the three countries (see Appendix 1).

England, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom (UK) consists of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. It has a parliamentary democracy with a constitutional monarch The ability to make and pass legislation is with Parliament which consists of the House of Lords, House of Commons, and the Sovereign (currently Queen Elizabeth II).

Although the Queen is the Head of State, executive power rests with the prime minister and her Cabinet, who must have the support of the House of Commons (Freedom in the World 2019, 2019). In addition, elected officials are chosen in frequent and fairly conducted elections in which coercion is comparatively uncommon and practically all adults can run for elected positions.

Citizens have a right to express themselves without the danger of severe punishment on political matters, to form relatively independent associations or organizations, including independent political parties and interest groups, and seek out alternative sources of information. Press freedom is legally protected which has prompted the media to be lively and competitive, espousing viewpoints spanning the political spectrum. In addition, freedom of assembly is generally respected and religious and academic freedom is protected in law and practice (Freedom in the World 2019, 2019). The UK has a stable democracy that regularly holds free elections and is home to a vibrant media sector.

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China, is an island off the eastern coast of the People’s Republic of China (China) Taiwan is a territory with its own democratically elected government, have differing views on the island’s status and relations with the mainland (Albert, 2018).

Taiwan is a multiparty representative democratic republic whose head of state is the president. The Taiwanese government structure is broken up into five branches, referred to as Yuans: the executive, legislative, examination, judicial and control.

The Central Election Commission (CEC) administers elections with mandates that no political party hold more than one third of the seats. The voting age was recently lowered from 20 to 18 and all permanent citizens are eligible to vote. Elected officials are able to exercise their constitutional powers to implement policy without interference. The polity is mostly self-governing with the exception of China’s involvement because Taiwan is considered to be under the umbrella of the Republic of China. Despite this, the country has made tremendous strides towards a democratic and just society.

Citizens have the right to practice any faith of their choosing, are constitutionally protected in civil and criminal matters, and have the right to freely assemble upon enactment of the 1988 Assembly and Parade Act. Media outlets broadcast different views and regulators work to protect interference from the Chinese government. With regards to social freedoms, citizenship laws protect against discrimination, and more recently, courts ruled it was unconstitutional to ban same-sex marriage. The main area of contention is the amount of influence China has over Taiwan’s political parties, policymaking, and media outlets.

United States

The US has a population of over 328 million and its geographic area spans 50 states, five territories, and the District of Columbia (DC), the location of the country’s capital (“U.S. and World Population”, n.d.). The US has a massive and complex government system consisting of a presidential republic with the president serving as both head of state and head of government. The President is responsible for implementing and enforcing the laws written by Congress and appoints the heads of the federal agencies, including up to 20 senior ministers (called the Cabinet) (The White House, n.d.). The Cabinet and independent federal agencies are responsible for the daily enforcement and administration of federal laws.

The legislative branch has two legislative bodies, the House of Representatives and the Senate which together form Congress. Congress enacts legislation, declares war, has the right to confirm or reject presidential appointments, and has substantial investigative powers. The US Vice President serves as President of the Senate and may cast the decisive vote in the event of a tie in the Senate (The White House, n.d.).

There are nine Supreme Court Justices including one Chief Justice (The White House, n.d.). Congress established 94 US district courts and 13 US court of appeals, courts inferior to the Supreme Court, who handle most of the federal cases and appeals (The White House, n.d.).

Elected officials are chosen in frequent and fairly conducted elections to an extent All national legislators are elected directly by voters in the districts or states they represent. However, though congressional elections are generally free and competitive, partisan gerrymandering, where the borders of House districts are redrawn regularly, is a growing concern. Practically all adults have the right to vote in the election of officials. The eligibility criteria includes US citizenship (either by birth or naturalization), meeting your state’s residency requirements, and being at least 18 years of age (“What are the requirements”, n.d.). Senators must be at least 30 years of age, have been a citizen of the US for nine years.

The US has a free, diverse, and constitutionally protected press. The media environment retains a high degree of pluralism, with newspapers, newsmagazines, traditional broadcasters, cable television networks, and news websites compete for readers and audiences. Internet access is widespread and unrestricted. The US also has a long tradition of religious and academic freedom and officials generally respect the constitutional right to public assembly. The freedom of assembly score improved because protests and demonstrations in 2018 featured less violence and fewer restrictions from the authorities than in the previous two years (Freedom in the World 2019, 2019).

Overall, the findings of the 2019 Freedom of the World Report (2019) concluded that the American people benefit from a vibrant political system, a strong rule-of-law tradition, robust freedoms of expression and religious belief, and a wide array of other civil liberties. However, in recent years its democratic institutions have suffered erosion, as reflected in partisan manipulation of the electoral process.

Health Care Systems

Every country is responsible for preparing its own arrangements for health care, but out of the 195 countries in the world, only about 40 countries have established health care systems (“Health Care Systems”, n.d.). While there are local-level variations, health care systems tend to follow four basic systems: the Beveridge Model, health care provided and financed by the government through tax payments; the Bismarck Model, health care provided through an insurance program usually financed jointly by employers and employees through payroll deduction, but coverage is universal and insurers do not make a profit; the National Health Insurance Model, health care provided by the private sector, but payments comes from a government-run insurance program that every citizen pays into; and the Out-of-Pocket Model, health care is always an out-of-pocket expense and thus, only the rich are able to afford health care(“Health Care Systems”, n.d.).

England and Taiwan both have universal health coverage, but follow different systems. The birthplace of the Beveridge Model was in Great Britain consisting of England, Scotland, and Wales, while Taiwan follows the National Health Insurance Model. As for the US, there are elements of all four models in their “fragmented national health care apparatus” where health coverage is determined by the category you fall into (“Health Care Systems”, n.d., para. 16). The following sections will discuss the health care systems of each of the three countries.

England

The National Health Service (NHS), one of the world’s largest publicly funded health service, provides health services to England and the rest of the UK. With the exception of some charges, such as prescriptions and optical and dental services, the NHS remains free at the point of use for anyone who is a UK resident.

History & Role of Government

Health Secretary Aneurin Bevan, the founder of the NHS, had a vision to provide high quality, free and sustainable healthcare for all. Bevan’s vision came into fruition when the National Health Service Act (NHS Act), a plan for health services to be paid by taxes and free at the point of use in England and Wales, was enacted in 1946 (“A brief history of the NHS”, n.d.). Scotland and Northern Ireland followed suit shortly after with their own laws.

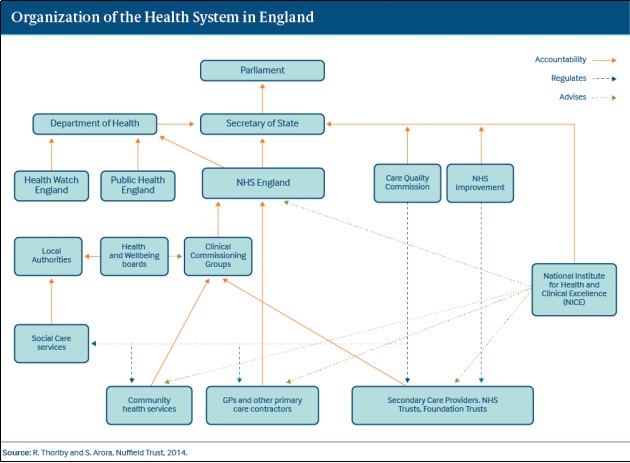

Currently in England, the Parliament and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) led by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care (DHSC Secretary) (currently Matt Hancock) are responsible for health legislation and general health policies. DHSC provides stewardship for the overall health care system by supporting and advising ministers and by acting as guardians of the health and social care framework to ensure they fit purposefully and work cohesively together.

NHS England

Daily responsibility for health care operations rests with the NHS. The NHS in England (NHS England) monitors the performance of the NHS nationally, supports commissioning locally, oversees 209 local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), and ensures that the objectives set out in an annual mandate by the DHSC Secretary are met, including efficiency and health goals (NHS England, n.d.).The structure of NHS England is split between the purchaser and provider. Purchasers (called Commissioners) are responsible for an area’s strategic healthcare planning and purchase healthcare for a defined population from providers of healthcare services. Within secondary care, CCGs are run by general practitioners (GPs) and other local healthcare professionals who assess local health needs and commission the services to meet them. There are currently 200 CCGs in England and they are responsible for 60 percent of the NHS budget (“How the NHS works”, n.d.). Providers of care (e.g. hospitals) are run by NHS hospital and foundation trusts. Various other trusts provide other essential services such as emergency call monitoring and patient transportation, specialists for complex and severe mental health problems, and social care services. Other local primary care services are provided through GP practices, NHS Walk-In Centres, dental practices, pharmacists, and optometrists. This internal market was designed to allow competition between providers for commissioner funds.

Who is Covered?

GP and nurse consultations in primary care, treatment provided by a GP, and other primary care services are free of charge to all registered NHS patients and temporary patients, patients in England for more than 24 hours and less than 3 months (Public Health England, 2019). For secondary care, entitlement to free healthcare in the UK’s health care system is based on an individually living lawfully in the UK on a properly settled basis. The measure of residence that the UK uses to determine entitlement is known as “ordinary residence”, meaning a person who is living in the UK on a lawful, voluntary and properly settled basis (Public Health England, 2019). Despite these exclusions, some services are free of charge irrespective of an individual’s country of normal residence as long as the overseas visitor has not travelled to the UK for the purpose of seeking that treatment. Examples include accident and emergency services, services provided for the diagnosis and treatment of a number of communicable diseases and sexually transmitted infections, family planning services, services for the treatment of a physical or mental condition caused by domestic or sexual violence, palliative care services provided by a registered palliative care charity or a community interest company (Public Health England, 2019). Additionally, there are a number of groups that are exempted from charges such as refugees, asylum seekers, children looked after by a local authority, and prisoners and immigration detainees (Public Health England, 2019).

What is Covered?

Although the precise scope of the NHS is not defined in statute or by legislation, it is the statutory duty of the DHSC Secretary to ensure comprehensive coverage and thus, in practice, NHS provides comprehensive preventive services, inpatient and outpatient drugs, clinically necessary dental care, some eye care, and mental health care (Arora & Thorlby, n.d.). The volume and scope of these services are generally decided by local governments.

There are some out-of-pocket expenditures for some services such as examinations for employment or insurance and travel certificates and insurance that are set nationally by the DHSC. Prescription drugs prescribed in NHS hospitals are free. Outpatient prescription drugs are relatively inexpensive at around $12.00 per prescription and discounts are available for those who need prescriptions refilled regularly (Arora & Thorlby, n.d.). As for NHS dentistry services, they have much higher co-payments at up to $310.00 per course of treatment. There are several groups exempted from paying prescription drug and dental payments and are eligible for free vision tests such as young people, students, pregnant women, recent mothers, and people with cancer (Arora & Thorlby, n.d.). Financial support is also available for young people and those with low income for corrective lenses and transportation costs to and from providers are covered for people who qualify for the NHS Low Income Scheme.

Health Delivery System

Table 1. provides an overview of how England’s delivery system is organized.

| Table 1. England Health Delivery System | ||

|---|---|---|

| Primary Care | Outpatient Specialist Care | Mental Health Services |

|

|

|

| Hospitals | After-Hours Care | Long-Term Care |

|

|

|

How is the System Financed?

The majority of funding for the NHS comes from general taxation and a smaller proportion comes from national insurance (e.g. a payroll tax). The NHS also receives income from other sources such as income from co-payments and people using NHS services as private patients. In 2017, the total healthcare expenditure increased by 1.1 percent (adjusted for inflation) from 2016 to $254.7 billion accounting for 9.6 percent of the GDP (“Healthcare expenditure”, 2019). Government financed healthcare expenditure accounted for 79 percent of total healthcare spending in 2017 at $200.9 billion, increasing by 0.3 percent while non-government healthcare financing increased by 4.3 percent (“Healthcare expenditures”, 2019).

Taiwan

Article 157 of Taiwan’s constitution calls for the national government to promote health maintenance and implement the public provision of health care for all citizens (Wu et al., 2010). The Taiwanese healthcare system is characterised by good accessibility, comprehensive coverage, short waiting times, low cost, and national data collection systems for planning and research. However, problems with their system include short consultation times resulting in quality care issues which is rooted in poor gatekeeping of specialist services. In health care, gatekeeping are policies that regulate the flow of patients to certain providers and services. It can be referrals to a specialist, assignment of a primary care provider, or approval from insurance companies for specific services. In Taiwan’s case, patients are able to see a specialist without a referral, leading to short consultation times and low quality of care.

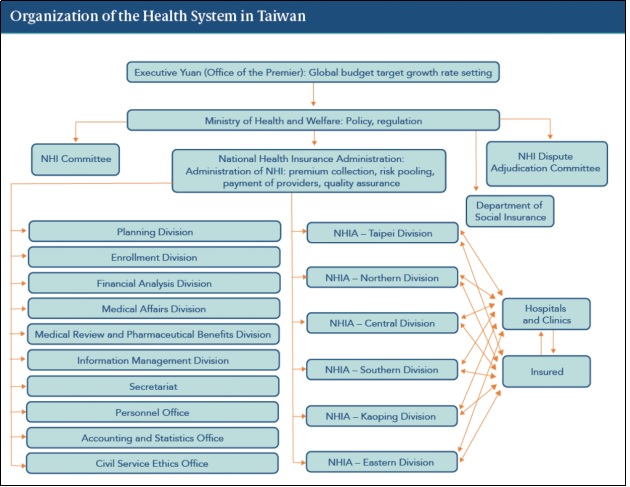

History of Health System & Role of Government

Prior to the introduction of the National Health Insurance (NHI) system, Taiwan used separate insurance schemes that covered roughly 60 percent of the population. This system included labour insurance, governmental employee insurance, farmers' health insurance and fishermen's health insurance (Cheng, 2019). In 1995, the Taiwanese government accepted the recommendation of Uwe Reinhardt, a high-level government adviser to Taiwan when it was planning to implement universal health insurance, to create a single-payer health care system (Cheng, 2019). Full implementation of the National Health Insurance (NHI) system started in 1995.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare is responsible for the NHI system. The division primarily responsible for a majority of the NHI is the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) which has 16 subcomponents to support the successful implementation of healthcare for the population. Some local governments offer additional benefits outside of the public insurance. The Taiwanese government has a multi-faceted quality assurance and monitoring initiatives. Quality care is ensured through a mixture of payment incentives, claims management and reviews, and transparency across regulatory agencies. These agencies include: the National Health Insurance Program Administration, Health Promotion Administration, and Medical Affairs Division. In addition to these safeguards, there are 10 national programs to ensure quality of care (Cheng, 2016).

NHI System

The NHI initiative integrated medical programs from existing insurance systems with the goal of improving efficiency and social justice by increasing coverage. The annual per capita cost for the single-payer program was 1,430 in 2016, only 6.3% of GDP (Shih-Chung, 2018). The NHI is a public program based on a single-payer model. Citizens are grouped into six main categories and 15 subcategories based on income and job status. The NHI payment system is a combination of retrospective and prospective payments with the unit of payment being a fee-for-service. In certain circumstances, a case payment or per diem payment is used. All services operate under a co-payment system except for annual physicals and cancer screenings. After the 1994 Act, private insurance became supplementary to the public system. It acts as a coinsurance providing clients with cash indemnities to be used as the patient sees fit (Cheng, 2016). Citizens are provided a NHI Integrated Circuit (IC) card that is used to identify the patient, store medical records, and connect the national insurer for billing and payment purposes. (Wu et al., 2010). The cloud-based information system that stores medical information, including MRIs and CT scans, makes it easier for providers, hospitals and clinics to coordinate care. In addition, patients are provided a cloud-based account called My Health Bank that allows them to check their medical records and access other important information. To ensure care, the government addressed health disparities affecting populations in remote areas, the NHI implemented the Integrated Delivery System (IDS) that strengthens medical capacities in resource-constrained areas (Shih-Chung, 2018).

Who is Covered?

The government requires all citizens and foreigners living in Taiwan for longer than 6 months to enroll in the NHI program. Individuals who are employed in Taiwan do not have to wait six months to register. There are six pathways which determine how a person registers in the NHI program. If a person is employed, they would register through their employer (insurance registration organization). If a person owns a company or corporation, then they are required to form a registration organization to enroll themselves, employees and dependents. Union and association (e.g Fishermen’s Association) members register through the entity. If a person is unemployed but a legally recognized dependent of an employed spouse, they would register through that organization. Lastly, if a person is unemployed and not eligible for dependent status, they would be required to register through their local administrative office (National Health Insurance Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare, n.d.).

What is Covered?

The NHI program benefits are comprehensive and covers primary care, specialists, prescriptions, dental, traditional Chinese medicine, home care, mental health and end-of-life care. Similar to how the NHIA determines the fee schedule and budget, the services covered are determined by consulting key stakeholders. Co-payments are required for physician visits and prescriptions. Inpatient care is subject to coinsurance, for example an additional private insurer. Copayments range from $2.50 to $12 USD (Cheng, 2016). In 2018, Taiwan’s 62% of the health expenditures were covered by NHI and 38% by out-of pocket spending (Health Care Resource Guide, 2018). Services for low-income and disadvantaged groups are subsidised through the NHIA.

Health Delivery System

Table 2. provides an overview of how Taiwan’s delivery system is organized.

| Table 2. Taiwan Health Delivery System | ||

|---|---|---|

| Primary Care | Outpatient Specialist Care | Mental Health Services |

|

|

|

| Hospitals | After-Hours Care | Long-Term Care |

|

|

|

|

1 Cheng, 2016 2 Health Care Resource Guide 2018 |

||

How is the System Financed?

Taiwan’s premium-based health insurance draws revenue to provide comprehensive coverage to 99.9% of the population. From 1998 to 2010, the expenditures exceeded the revenues generated, forcing the Ministry of Health to raise the premium rate from 4.55% to 5.17% of payroll income. Revenue breakdown: 68% from payroll-based premiums, 27% from supplementary premiums from non-payroll income (bonuses, fees etc), and 5% from lottery and tobacco tax. Taiwan’s lottery system is a public welfare business system that directly funds resources for the underprivileged. While the winnings are taxed, winners are also encouraged to donate a portion to the fund to further benefit the people (Taiwan Lottery). Payroll-based premium further breaks down to 23% covered by the government, 38% from households (based on per capita calculations that cap at four people per household), and 39% coming from employers. Cost containment is regulated through the National Health Insurance global budget system. The Taiwan health care system has one the lowest administrative cost compared to other systems due to their IT-driven system used by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Cheng, 2016).

United States

Unlike England and Taiwan, the US does not have a uniform health care system, does not provide universal health care coverage, and only recently enacted legislation mandating health care coverage for almost everyone. The complex hybrid system in the US is the most expensive health care system in the world claiming 17.2 percent of the country’s GDP in 2017.

History of the Health System & Role of Government

Prior to the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (also known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and nicknamed “Obamacare”) in 2010, the US public insurance system and the lack of access to affordable private coverage left millions of people without health insurance. The U.S primarily relied on employers to voluntarily provide health insurance to their employee, partners, and dependents. The system was financed through a mixture of public payers and private insurers (Law, Greenberg, & Kinchen, 1992). By 2013, the year before the major coverage provisions of the ACA went into effect, more than 44 million non-elderly Americans lacked coverage (Damico, Garfield, & Orgera, 2019). Millions of Americans were discriminated against because of a pre-existing condition and falling ill had the potential to cut you out of an insurance plan entirely because of one’s inability to pay.

The state's progressive vision of universal coverage and the conservative idea of market competition are what formed the blueprint for Obamacare: that everyone should have access to quality, affordable health care, and no one should ever go broke just because they get sick.

After the full enactment of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) starting in 2014, Medicaid coverage, a federal and state program that helps with medical costs for some people with limited income and resources, expanded to nearly all adults with incomes at or below 138 percent of poverty in states that have adopted the expansion and tax credits are now available for people with incomes up to 400 percent of poverty who purchase coverage through a health insurance marketplace (Damico et al., 2019). Millions of people enrolled in ACA coverage thus lowering the uninsured rate to a historic low by 2016 (Damico et al., 2019).

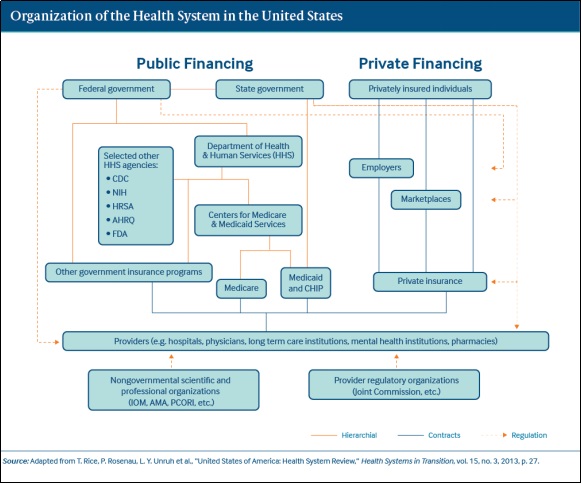

The federal government, in conjunction with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), work with state governments to provide health care and resources to low-income, elderly and disabled people (see Appendix 4 for relationship between government and health care administration). State governments are responsible for regulating private insurance and determining the subsidies for low-income people (The Commonwealth Fund, n.d).

Multi-Payer Health System

The ACA has established a shared responsibility between government, employers, and individuals to ensure all Americans have access to quality health insurance. The U.S operates under a multi-payer system that contains elements from all four health system models: the Beveridge, Bismarck, National Health Insurance, and Out-of-Pocket Models. While the CMS administers Medicare, a federal program for adults aged 65 and older and some people with disabilities, and works in partnership with state governments to administer both Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), a conglomeration of federal–state programs for certain low-income populations, private insurance is regulated mostly at the state level (The Commonwealth Fund, n.d.). State and federally administered health insurance marketplaces were established to provide additional access to private insurance coverage with income-based premium subsidies for low- and middle-income people. In addition, states were given the option of participating in a federally subsidized expansion of Medicaid eligibility.

Many critics consider this system to be a fragmented or patchwork system because of the inconsistencies with delivery that create gaps in coverage for citizens (Healthcare Systems - Four Basic Models, n.d). It is estimated that about 8.6 percent of the population is without health coverage. In 2014, health care spending in the United States per capita was $9,364 and $1,034 for out-of-pocket spending. (The Commonwealth fund, n.d).

Who is Covered?

Due to the fact that the U.S operates on a multi-payer system, coverage is sporadic and varies. This is evident by the roughly 28.5 million Americans currently without coverage. According to the 2017 U.S. Census, 67% of insured Americans were covered by private insurance and 37% by government sponsored programs. The subtypes of health coverage included: employer-based (56%), Medicaid (19%), Medicare (17%), direct-purchase coverage (16%), and military coverage (4.8%) (Berchick, Hood & Barnett, 2018). While there are many safety net and low-income programs, this patchwork network still leaves many gaps in coverage, leaving people without direct access to affordable care.

What is Covered?

The ACA sets requirements for essential services that must be covered under health plans offered in the markets. These services are: ambulatory patient services, emergency services, hospitalization, maternity, mental health, prescription drugs, rehabilitative services, laboratory services, preventative services, and pediatric care (including dental and vision). As mentioned above, each state determines the breadth of services covered through regulation. Safety nets in the U.S healthcare system are comprised of Federally-Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), Medicaid coverage, public hospitals, and local health clinics using cost-sharing, sliding-scale, or subsidies as a fee structure. It is known as a “patchwork” system because of the gaps present in the network (The Commonwealth fund, n.d).

Health Delivery System

Table 3. provides an overview of how the US’s delivery system is organized.

| Table 3.. US Health Delivery System | ||

|---|---|---|

| Primary Care | Outpatient Specialist Care | Mental Health Services |

|

|

|

| Hospitals | After-Hours Care | Long-Term Care |

|

|

|

|

1 The Commonwealth Fund, n.d |

||

How is the System Financed?

The U.S healthcare system is financed through a mix of public and private spending, known as a multi-payer system (See Appendix 4). Medicare is financed through a mix of general federal revenues, payroll taxes, and premiums. In addition, premium subsidies are offered through federal tax credits. Medicaid is administered through the state and is tax-funded. Depending on the state’s per capita income, the federal government will match between 50%-75% of the Medicaid expenditures. In the U.S, private insurers are regulated by the state’s insurance commission division and can be for-profit or non-profit. Employers who offer health insurance qualify for tax (The Commonwealth fund, n.d).

Comparative Analysis

As discussed in the previous sections, two countries with similar health care systems (England and Taiwan) and one country with a different health care system were selected because their health care systems provide universal coverage while the US was selected because its health care system is the exact opposite. Although, in theory, England and Taiwan’s systems should be quite similar, if not the same entirely, their systems have unique qualities that originate from their democratic structures and cultural influences. The next sections will discuss key distinctions between England and Taiwan’s health care systems. In addition, some similarities between the US health care system and England and Taiwan’s health care systems will be analyzed. Collectively, the differences and similarities will lead into the last section of this report where insights, patterns and recommendations to improve the systems will be discussed.

Differences Between England & Taiwan

Advocating for Universal Coverage

Uwe Reinhardt, the architect of Taiwan’s healthcare system, based his recommendation on three policy considerations. First, a single-payer system is effective in controlling cost; this was a major policy goal of the government as health spending in Taiwan was growing rapidly. Second, a single-payer system is equitable: coverage is universal and all insured are treated equally regardless of ability to pay or preexisting conditions. Third, a single payer system is administratively simple and easy for the public to understand. The NHI has achieved all three policy goals. Reinhardt also suggested that Taiwan retain its predominantly private delivery system. He believed that the private sector has an important role to play in a nation’s health care system. As long as financing and payment were within the purview of government, a mixed delivery system of private and public providers could work well within a single-payer framework. Taiwan’s experience has shown this to indeed be the case.

Compared to Taiwan, the creation of the NHS was the product of decades of hard work and motivation from various people who felt the current healthcare system was insufficient and needed to be revolutionized. Calls for health care reform started in the 1900s, but was not effectuated until the London County Council took over the responsibility for about140 hospitals, medical schools and other institutions in 1930 after the abolition of the Metropolitan Asylums Board (Brain, n.d.). World War II led to the creation of the Emergency Hospital Service to care for the wounded, making these services dependent on the government (Brain, n.d.). By 1941, the Ministry of Health was in the process of agreeing to a post-war health policy with the aim to service the entire general public (Brain, n.d.). A year later, comprehensive health and rehabilitation services was supported by the House of Commons and the Cabinet eventually endorsed the guidelines for the NHS which included how it would be funded from general taxation and not national insurance (Brain, n.d.). Everyone was also entitled to treatment including visitors to the country and it would be provided free at the point of delivery. These ideas were taken on by the next Minister of Health, Aneurin Bevan, who successfully campaigned to structure the NHS as we see it today (Brain, n.d.).

Method of Funding

England uses a tax-based method of funding while Taiwan using an insurance premium method. Taiwan’s method of funding is comprised of payroll and non-payroll income with supplemental funding from the government. An area of contention for Taiwan is its political issues with raising premiums to meet new rising cost. It is speculated that at its current rate, the Taiwanese government will have to increase its supplemental funding, which could create a burden on the economy. England’s tax-based method mirrors a more socialized approach than the Taiwan system. Based on the principles of decentralization, England uses a bottom-up and top-down approach to funding. England’s funding power is largely with the people by way of tax collection. Taiwan uses a top-down approach in regards to funding and policy making power, with a mix of both in administration of the national healthcare program. Funding power and policy making power is centralized at the top with the Legislative Yuan having the final sign off on premium budgets. Administrative power, however, is shared with national and localities by way of sub divisions.

Medical Providers

In Taiwan, providers are largely private and generally free to compete with one another. The Taiwanese system providers earn their income through patient visits, prescriptions, and procedures. In addition, they provide additional services like cosmetic surgery, laser treatment, etc. This expands their income net and allows them to operate in a more competitive manner. In England, GPs are contracted by the government and their salaries are negotiated by the association who represents them and the government. GPs earn income through a mixture of capitation and reimbursed directly by the government every month (mostly seamless process because the data being input are the patients they are serving. If there are additional services, this is the only data that needs to be input manually into the system). Most services are free of charge at point of use and when there are out-of-pocket expenses, it is relatively inexpensive and many groups are eligible for exemptions. Only additional, non-necessary services (some vision, dental, etc.) require a fee. Taiwan does not require registration to see a physician as they employ an innovative mechanism using a cloud system that allows citizens to store their basic and most recent medical information so that they can see any provider. It also allows for seamless claims management. Whereas England requires registration to see a physician (who are typically the first point in contact for patients). This difference is economic - England funds their providers directly through negotiated contracts whereas Taiwanese providers have more opportunities to earn additional income and compete with one another. Both national healthcare systems draw public funding, but the Taiwanese system incorporates market principles from the private sector by allowing providers to operate privately (not government contractors)and increase their revenue by offering other services. It can also be argued that because England requires patients to register with a physician, thus eliminating provider competition and stagnating overall pay.

Accessibility

While England struggles with long wait times and limited supply of doctors, but high demand for services, Taiwan’s citizens enjoy ease of accesses to both primary care and specialist. However, Taiwan’s lack of gatekeeping - referrals to specialist and assigned primary care providers - creates issues with quality of care due to short visit times. One could argue that a health system that fails to address quality of care, regardless of coverage, fails as a system. England’s Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) (Wu, Majeed & Ku, 2010) works to address the issues currently faced in Taiwan. The government’s administrative initiatives to maintain quality of care are far better in this case than Taiwan’s.

Similarities Between US & England

History

Despite the current versions of their health care systems starting at drastically different times, the 1940s for England and 2010s for the US, and the scope covered by the government, the reasoning behind their establishments is essentially the same. Before the NHS Act was enacted in 1946, health care in England was incredibly expensive and only provided services to the working population, virtually excluding most, if not all women and children. As for the US, in 2013, the year before the ACA was fully implemented, over 44 million non-elderly Americans did not have health insurance largely due to private insurance plans being unaffordable. British and American elected officials created reformed their health care systems because the number of uninsured were disproportionately larger than the insured population.

Health Legislation

In the US and England, health legislation and general health policies are handled on the federal level. In England, legislative power for health legislation is with the Parliament and DHSC supervises and manages the overall health care system. In the US, the federal government creates/revises general health care regulations and works with state governments to provide health care and resources to low-income, elderly and disabled people. While the scope and population coverage is different, health legislation is centralized.

Physicians

In both countries, physicians providing primary care are paid through a mixture of negotiated capitation. In England, most GPs (66 percent) are private contractors, and approximately 56 percent of practices operate under the national General Medical Services contracts, negotiated between the British Medical Association (representing doctors) and the government (Arora & Thorlby, n.d.). These provide payment using a mixture of capitation to cover essential services (representing about 60 percent of income), optional fee-for-service payments for additional services (e.g., vaccines for at-risk populations, about 15%), and an optional performance-related scheme (about 10 percent) (Arora & Thorlby, n.d.) Capitation is adjusted for age and gender, local levels of morbidity and mortality, the number of patients in nursing and residential homes, patient list turnover, and a market-forces factor for staff costs as compared with those of other practices. Performance bonuses are given mainly on evidence-based clinical interventions and care coordination for chronic illnesses. In the US, physicians are paid through a combination of methods as well, including negotiated fees (private insurance), capitation (private insurance), and administratively set fees (public insurance) (The Commonwealth Fund, n.d.). Physicians can also be given financial incentives, made available by some private insurers and public programs like Medicare, based on various quality and cost performance criteria.

Similarities Between US & Taiwan

Government

In regards to health care, both Taiwan and the U.S exhibit characteristics of deconcentration (Chaturvedi, 2019) with accountability at the federal levels. Politically, in both systems healthcare decisions are made at the federal levels between the executive and legislative branches (called Yuans in Taiwan). While the U.S provides power to the states for regulation, the ACA is mandated at the top. Economically, both systems decide on either premium rates (Taiwan) or Medicare/Medical state reimbursement rates at the top of the system. Giving little power to localities in the decision making. Administratively, in the U.S, the CMS administers Medicare and Medicaid and sets the basic coverage requirements for states to follow. In Taiwan, the NIHA, by way of the Executive and Legislative Yuans, set rates and determine how the system will roll out.

Short Wait Time

Both systems have short wait times, but for vastly different reasons. In the U.S., short wait times are attributed to gatekeepers and insurance networks controlling the influx of patients to specific providers. Whereas in the Taiwanese system, the lack of gatekeepers allow patients to quickly accesses providers and specialist at any time. However, the quality of care suffers in the Taiwanese system due to short doctor visits and high volume of patients; in the U.S., quality of care for low-income people are low because many specialists refuse to see patients because of the lower reimbursement rates.

Financial Problems

In Taiwan, the payment system is formulated in global budget and based on care determined by the LegislativeYuan. NHI does not take enough money from premium payments to cover healthcare provided, which means the government has to provide additional funds to supplement. The problem is political - any premium increase would have to be approved by the Legislative Yuan and they are typically at odds with the Executive Yuan. In the U.S, the issue is cost containment. 10 Payers have attempted to control cost growth through a combination of selective provider contracting, price negotiations and controls, utilization control practices, risk-sharing payment methods, and managed care. In the end, the U.S still pays exponentially higher for healthcare compared to other nations, like Taiwan.

Recommendations

The following sections provide recommendations for improving the health care systems of each country:

England

Improve Wait Times By Hiring More Physicians

The NHS currently has a four hour target for seeing and treating patients in UK hospital accident and emergency departments (A&E hospitals). However, wait times continue to be much longer with the worst performance occurring in January 2018 when only 77.1 percent of patients were dealt with within four hours (Campbell & Duncan, 2018). Performance data from the NHS England also showed patients due to have planned surgery have been waiting longer and longer for their operations (Campbell & Duncan, 2018). The limited number of physicians in the NHS is likely to be one of the reasons for the prolonged wait times. In 2015, there were 34,592 general practitioners (full-time equivalents) in 7,674 practices, with an average of 7,450 patients per practice and 1,530 patients per GP (Arora & Thorlby, n.d.). The easiest solution would be to hire more physicians, but the NHS would conduct a comprehensive analysis of the situation to understand the underlying problem. They may find that physicians from abroad who are looking to become GPs in the UK are struggling to obtain employment licenses, or the profession is simply not as attractive in the UK because it does not pay as well as other developed countries (Donnelley, 2018). Regardless, the NHS must conduct the necessary analyses to understand the problem and then develop strategies to increase the number of physicians. The availability of more physicians will likely lead to a decrease in wait times.

Surveillance

Concerns about the effects of mass surveillance on free and open private discussion has persisted in recent years which took some points off of the UK’s civil liberties rating and overall aggregated score. The 2016 Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) requires communications companies to store metadata on customers’ activity for 12 months and, in some cases, allows this information to be accessed by police and other security officials without a warrant (Freedom in the World 2019, 2019). In September, the European Court of Human Rights declared in a landmark ruling that the UK’s surveillance program violates the right to respect for private and family life/communications and lacks safeguards (Freedom in the World 2019, 2019). In response to the High Court ruling, new regulations were enacted in October, which allow authorities to only access communications data while investigating serious crimes, and require the approval of an independent commission to obtain such data (Freedom in the World 2019, 2019).

Taiwan

Restructuring Premiums

The premium structure in Taiwan, while affordable, will not scale with population growth rates and will have long-term effects on the country's economic infrastructure. As mentioned in the financing section, from 1998 to 2010, the expenditures exceeded the revenues generated, which forced the Ministry of Health to raise the premium rate from 4.55% to 5.17% of payroll income. It is recommended that the Ministry of Health (MOH) work with the Legislative Yuan to raise the non-payroll income and lottery tax rather than the premium rate. Tobacco tax is currently under fire for being too high and the DPP is considering lowering the tax and funding long-term care from another source (Yu et al., 2019). Thus, in the interim, it is suggested that non-payroll income be taxed at a higher rate. In regards to Taiwan’s welfare lottery system, instead on solely relying on a minimal tax and infrequent donations from winners, it is recommended that Taiwan implement a tax tier system. Each tier would have a different tax rate, which would increase the amount of taxes collected, thus having the ability offset the amount being supplemented from the general fund. By avoiding the tobacco tax, and focusing on taxing supplemental income areas, it is assumed that the Legislative Yuan and policy makers would face minimal push back.

Expansion of Long-Term Care Services

By raising the rate on nonpayroll and lottery tax, the government could create a fund for the country’s aging population. In regards to the aging population, Taiwan’s health system does not have a formal long-term care program in place which will create future burdens as the country continues to develop. To help support this initiative, policy makers and health advocates could argue the economic and social benefits to developing a long-term care program.

Improve Quality of Care Using Gatekeeping Systems

As the literature and population opinion suggest, the most immediate need for this health system is to increase the quality of care. Taiwan’s quality of care issue is rooted in the fact that there are no gatekeepers regulating the flow of patients to primary care physicians and specialist. Currently, the country uses three strategies to address the issue (payment incentives, transparency, and claims review), but none of them address the root cause, gatekeeping. The two other systems in this analysis use referral or networks as a method to contain overcrowded providers. Taiwan system allows patients to see a specialist as easily as they see a provider. Due to the high-volume of patients, providers on average spend five minutes or less with patients, leading to the low quality of care. It is recommended that the MOH implement a referral system and coordinate with localities to determine if networks of care could be enforced. In addition, the cloud-based system could be leveraged to help with coordination between localities and patients. While this seems to be the most sustainable solution, it would present economic issues for providers.

United States

Expansion of the ACA

While the ACA has provided additional coverage to those who were without, there still is the issue of their “patchwork” issue. The government should work at all levels to centralize funding. In particular, the federal government should increase funding to rural and community clinics that serve underserved populations so they can be better equity at filling the gaps of covered until a better, more universal solution is available.

Address Data and Surveillance Issues

While Americans have strong views about the importance of control over their personal information and freedom from surveillance in daily life, the US should look into how similar Taiwan’s cloud based system is to the applications and websites developed by American health care providers that already give patients access to their medical records electronically and even meet with their doctors through video calls. Finding similarities may help Americans become more comfortable with a cloud based system like Taiwan’s. Implementation of this system may allow patients to easily change their physicians and specialists as needed and provide hospitals with their medical records seamlessly in emergency situations. This may also be used as an easy way to verify health coverage and make electronic payments. Further, implementing this program early on may make the transition to universal health care much easier if the US decides to move in this direction.

Test Universal Healthcare at the State Level

A universal health system implemented at the state level, rather than the federal level will allow for more flexibility regionally and alleviate the concern of “big” government’s involvement at lower levels. This will also allow states to have autonomy while providing comprehensive care to the citizens. Once a proven framework has been determined, the federal government can mandate basic requirements, similar to the ACA, for states to follow while leaving most of the power at the state-level in regards to regulation, level and extent of services provided, and the role of private insurance companies.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Democratic Evaluation Toolkit: 9 Simple Rules

Chaturvedi, A. (2019, February 21). Comparing democratic systems [Powerpoint presentation].

Retrieved from https://ilearn.sfsu.edu/ay1819/course/view.php?id=16859

Appendix 2. Organization of the Health System in England

Arora, S. & Thorlby, R. (n.d.). The English Health Care System. Retrieved on May 11, 2019,

from https://international.commonwealthfund.org/countries/england/

Appendix 3. Organization of the Health System in Taiwan

Cheng, T. (n.d.). The Taiwan Health Care System. Retrieved May 5, 2019, from

https://international.commonwealthfund.org/countries/taiwan/

Appendix 4. Organization of the Health System in the US

The Commonwealth Fund. (n.d.). The U.S Health Care System. Retrieved May 13, 2019, from

https://international.commonwealthfund.org/countries/united_states/

Reference

- A brief history of the NHS. (n.d.). In BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/timelines/zmjbd6f

- Access to Health Services. (n.d.). Retrieved on May 5, 2019, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Access-to-Health-Services#1

- Agence France-Presse (2015, April 30). Britain’s political system explained [Video file].

- Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HkfC8J95lGw

- Albert, E. (2018, June 15). China-Taiwan Relations. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-taiwan-relations

- Arora, S. & Thorlby, R. (n.d.). The English Health Care System. Retrieved on May 11, 2019, from https://international.commonwealthfund.org/countries/england/

- Berchick, E. R., Hood, E., & Barnett, J. C. (2018, September 12). Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-264.html

- Brain, J. (n.d.). The birth of the NHS. Retrieved from https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Birth-of-the-NHS/

- Campbell, D. & Duncan, P. (2018, February 8). Patients suffering as direct result of NHS wait-time failures. In The Guardian. Retrieved on May 21, 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/feb/08/patients-suffering-direct-result-nhs-wait-time-failures

- Chaturvedi, A. (2019, February 21). Comparing democratic systems [Powerpoint presentation]. Retrieved from https://ilearn.sfsu.edu/ay1819/course/view.php?id=16859

- Chaturvedi, A. (2019, February 28). Decentralization, Local Governments, and Accountability [Powerpoint presentation]. Retrieved from https://ilearn.sfsu.edu/ay1819/course/view.php?id=16859

- Cheng, T. (2016). The Taiwan Health Care System. Retrieved May 5, 2019, from https://international.commonwealthfund.org/countries/taiwan/

- Cheng, T. (2019, February 6). Health care spending in the US and Taiwan: A response to It’s still the Prices, Stupid, And A Tribute To Uwe Reinhardt. Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190206.305164/full/

- The Commonwealth Fund. (n.d.). The U.S Health Care System. Retrieved May 13, 2019, from https://international.commonwealthfund.org/countries/united_states/

- Dahl, R. (1982). Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Damico, A., Garfield, R. & Orgera, K. (2019, January 25). The uninsured and the ACA: A primer - Key facts about health insurance and the uninsured amidst changes to the Affordable Care Act. Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://www.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-and-the-aca-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-amidst-changes-to-the-affordable-care-act/

- Department of Health and Social Care. (n.d.). In GOV.UK. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-of-health-and-social-care

- Donnelley, L. (2018, August 9). NHS needs thousands of overseas doctors to plug GP shortage.

- In The Telegraph. Retrieved on May 21, 2019, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/08/09/nhs-needs-thousands-overseas-doctors-plu g-gp-shortage/

- Freedom in the World 2019. (2019). Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2019/democracy-in-retreat

- General elections. (n.d.). In www.parliament.uk. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/education/about-your-parliament/general-elections/

- General election 2015 explained: Seats. (2015, May 3). In Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/generalelection/general-election-2015-explained-seats-10222716.html

- Healthcare expenditure, UK health accounts: 2017. (2019, April 25). In Office of National Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthcaresystem /bulletins/ukhealthaccounts/2017

- Health care systems- Four basic models. (n.d.). In Physicians for a National Health Program. Retrieved from http://www.pnhp.org/single_payer_resources/health_care_systems_four_basic_models.php

- Health Care Resource Guide: Taiwan. (2018, October 19). Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://2016.export.gov/industry/health/healthcareresourceguide/eg_main_108622.asp

- How the NHS works. (2018, December 7). In British Medical Association. Retrieved from https://www.bma.org.uk/advice/work-life-support/life-and-work-in-the-uk/how-the-nhs-works

- Law, N. D., Greenberg, G., & Kinchen, K. (1992). A layman's guide to the U.S. health care system. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review, 151-169. Retrieved May 12, 2019

- National Health Insurance Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare. (n.d.). Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://www.nhi.gov.tw/english/Content_List.aspx?n=ED4A30E51A609E49&topn=ED4A30E51A609E49

- NHS England (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/

- Political System. (n.d.). Retrieved May 5, 2019, from https://taiwan.gov.tw/

- Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: mid-2017.

- (n.d.). In Office of National Statistics. Retrieved April 28, 2019, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/ bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/mid2017

- Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: mid-2017.

- (n.d.). In Office of National Statistics. Retrieved April 28, 2019, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populti

- onestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/mid2017

- Pringle, E. (n.d.). History of the National Health Service. Britain. Retrieved from https://www.britain-magazine.com/features/history/nhs-history/

- Public Health England. (2019, January 24). NHS entitlements: migrant health guide. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/nhs-entitlements-migrant-health-guide

- Schmitter, P. C., & Karl, T. L. (1991). What Democracy Is. . . and Is Not. Journal of Democracy, 2(3), 75-88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1991.0033

- Sen, A., & Lamont, T. (2015). Universal Health Care: The Affordable Dream (Vol. 4, Global Health, Rep.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Public Health Review Shih-Chung, C. (2018, May 02). Taiwan's National Health Insurance: A Model for Universal Health Coverage. Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://thediplomat.com/2018/05/taiwans-national-health-insurance-a-model-for-universal-health-coverage/

- Taiwan Lottery. (n.d.). Retrieved May 21, 2019, from http://www.taiwanlottery.com.tw/eng_about_tlc.asp

- Taiwan Population. (2019). Retrieved 2019-05-12, from http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/taiwan/

- Therrien, A. (2018, September 25). Life expectancy progress in UK 'stops for first time'. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/health-45638646

- The two-house system. (n.d.). In www.parliament.uk. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/about/how/role/system/

- The U.S. health care system: An international perspective. (2016). In Department for Professional Employees. Retrieved from https://dpeaflcio.org/programs-publications/issue-fact-sheets/the-u-s-health-care-system-an-international-perspective/

- UK Parliament (2014, September 4). Parliament structure explained [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlPSAOa4vR4

- Universal Health Coverage and Health Financing. (n.d.). Retrieved May 5, 2019, from https://www.who.int/health_financing/universal_coverage_definition/en/

- United States Population. (2019). Retrieved 2019-05-12, from http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/united-states-population/

- U.S. and world population clock. (n.d.). In U.S Census. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/popclock/

- What are the requirements to vote in federal elections? (n.d.). In LawInfo. Retrieved from https://resources.lawinfo.com/civil-rights/right-to-vote/what-are-the-requirements-to-be-eligible-to-v.html

- What is health financing for universal coverage? In World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health_financing/universal_coverage_definition/en/

- The White House. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/

- Who can stand as an MP? (n.d.). In www.parliament.uk. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/about/mps-and-lords/members/electing-mps/candidates/

- Who is eligible to vote at a UK general election? (n.d.). In The Electoral Commission. Retrieved from https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/faq/voting-and-registration/who-is-eligible-to-vote-at-a-uk-general-election

- Wu, T., Majeed, A., & Kuo, K. N. (2010). An Overview of the healthcare System in Taiwan. London Journal of Primary Care, 3(2), 115-119. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- Yu, M., Cheng-chung, W., Chuan, K., & Yen, W. (2019, March 3). Legislator Calls for Tobacco Cut, Citing Public Outcry. Retrieved May 21, 2019, from http://focustaiwan.tw/news/aipl/201903030013.aspx

Brandon Lewis Venerable

MPA Candidate, School of Public Affairs and Civic Management, San Francisco State University

Carmelisa Jurene Morales

MPA Candidate, School of Public Affairs and Civic Management, San Francisco State University

Recent Articles

- James Silverman ( Founder, U&I Global) interviews Arpit Chaturvedi (Co-founder and CEO, GPI) on AGENDA 2030- DO WE WANT IT? CENTRALISATION AND THE SDG’S

- Big Tech on Section 230 – Censorship or Disregard?

- Global Policy Insights (GPI) Annual India Colloquium.

- Antitrust hearing only a beginning on accountability

- The Commonwealth: Optimising Networks & Opportunities for the 21st Century

- Population Data in the Time of a Pandemic

- The Disconnect with Ground Realities

- Models to Make Vocational Training Work in India

- Comparing Health Care Systems in England, Taiwan, and the United States

- Commonwealth In Dialogue : Academic Series

- Are we rewarding fence-sitters and free-riders by relaxing penalties on CSR law violations?

- Changing Economic Models: From Mixed Economy to Liberalization, Privatization, and Globalization in India

- Goods and Services Tax (GST) – a Seventeen Year Ordeal to a Uniform Indirect Tax Regime in India

-

Commonwealth In Dialogue: International leader Series

Podcast: Patsy Robertson, Chair Ramphall institute in conversation with Uday Nagaraju, Executive President and Neha Dewan, Fellow & Researcher about Commonwealth - Creating a future-proof curriculum for the digital age

- Commonwealth In Dialogue: High Commissioner Series": H.E Dr. Asha-Rose Migiro

- High Commissioner of the United Republic of Tanzania to the United Kingdom & Republic of Ireland in conversation with Uday Nagaraju, Executive

- Commonwealth In Dialogue: Parliamentary Speaker Series

- Louisa Wall - Marriage Equality in New Zealand

- Hon An치lu Farrugia, Speaker of the House of Representatives Parliament of Malta & Secretary General CPA Small branches speaks to Uday Nagaraju, Executive President & Co-founder of Global Policy Insights on Commonwealth, CPA Small branches and Parliament of Malta

- Commonwealth Series: Cyprus High Commissioner to the UK H.E Euripides L Evriviades interviewed by Uday Nagaraju, Executive President Global Policy Insights & Neha Dewan, Fellow & Researcher

- Global Policycast: Ex-Minister of State in the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands- Victor Cummings interviewed by Arpit Chaturvedi, C.E.O Global Policy Insights.

- Global Policycast: Ex-Minister of Youth, Paraguay- Magali Caceres interviewed by Arpit Chaturvedi, C.E.O Global Policy Insights.

- Commonwealth Series: CPA Secretary-General Akbar Khan interviewed by Uday Nagaraju, Executive President Global Policy Insights & Divya Pamulaparthy

- The Perils of Decentralization and other Buzzwords in Governance and Policymaking