National Imagination & The invisible enemy: State responses to COVID-19 and Implications for International Security

Posted On Wednesday, April 29, 2020 by Neha Dewan under Sustainability and International Strategic Studies

National Imagination & The invisible enemy: State responses to COVID-19 and Implications for International Security

ABSTRACT

This piece primarily focuses on the state responses to COVID-19 by international governments. By looking at the cases of geographically distanced Israel, Brazil, Hungary and the United States among others, it delves into the terminology selected by state leaders across the globe to demonstrate their utilisation of ‘war-time’ responses to the pandemic. Through critical analyses of political speeches and rhetoric, it further explores their inter-relationship with securitization (Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde 1998), ultimately comparing the official narratives with the actual preparedness of the state or the lack thereof. It demonstrates two findings for the dependency on war, ‘the consolidation of power’ and ‘the narrative of nationalism’. In addition, it also provides a brief insight into the lasting implications of actions and legislations employed to support the war discourse, for instance, the heightening of surveillance measures and curbing of democratic freedoms.

Overall, it attempts to answer the following question: why have state leaders responded to a pandemic with war-time analogies and to what extent will this have implications on the international order post COVID-19?

THE GLOBAL PANDEMIC

Globally, over 1.9 million people have been infected with the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). The world’s military stronghold, the United States alone has recorded 608,458 cases just as a war-torn Yemen reports its first. This is likely to be the only point in history where the political consequences can be equally devastating for both.

Everyday, COVID-19 claims new victims indiscriminately, leaving billions of individuals across different socio-economic milieux in lockdowns accompanied by fear, anxiety and uncertainty. The most fundamental duties of the state are being brought under question, fast changing the relationship between the state and the citizens. As the social contract with the state comes under evaluation, for now the only recourse for many is to trust their political leaders with the common good.

Political action in a time of crisis leaves leaders with limited choices, which can often prove fatal to their electoral campaigns and in some cases question the constitution of their office itself. This is a pandemic which has made the greenback feeble, a strong world economy paralytic, re-defined the ‘essential roles’ in a society, fuelled ideological wars, worsened humanitarian crisis and most importantly, tested political offices against a threat that renders nuclear stockpiles and munition bunkers futile. Amidst an uneasy normality and a miasma of difficult bargains, one questions whether personality cults and charismatic cabinets offer much against pandemics.

The coronavirus pandemic presents itself with a myriad of crises which have borne the unfortunate result of political chiefs either questioning their own capacities or severely overstating them. As the novel virus emerging out of Wuhan acquired deep roots in the West, it did much to damage the morale of seemingly invincible powers. Reliant only on epidemiological modelling and whipsawed between saving lives or the economy first, administrative ethics, morals and ideology have come to the forefront like never before. National addresses and earnest appeals made by Heads of States are being dominated by unrelenting and urgent references to the Great Wars, the Marshall Plan, the Middle Eastern war of 1967, even the mythological 'Mahabharata war', accompanied by a call to ‘alms’. Geographically distant and politically divergent Israel, Brazil, China, United States, and several others were found resonating in each other’s responses to the ‘war’ against a hidden or ‘invisible’ enemy that compelled a narrative and one that too would fit within the national imagination.

The world is at war with a hidden enemy. WE WILL WIN!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 17, 2020

History is testimony to the dependency of nation-states on national narratives, myths and selected pasts, but one would not intuitively expect their invocation in a viral outbreak. The allegory of war in a pandemic I argue, effectively demonstrates two political reasonings, the consequences of both of which will have drastic implications for the post COVID-19 world order.

First, the preponderance of war-time analogies has entitled office-holders to respond with ‘all means necessary’, which they allude can be best exercised through the consolidation of power.

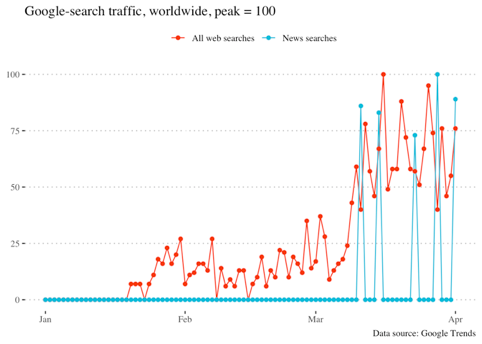

An analysis of aggregated worldwide Google-search data from the onset of the pandemic represents a spike in the utilisation of war terminology in relation to coronavirus, peaking in the month of March and carrying out into April 2020, as depicted in Figure 1 below. Interestingly, a co-occurrence with Google-news search data for the same time period can also be observed. The graph underpins a broader, representative pattern substantiated by acts of narrative construction by state actors worldwide.

The established trend is telling, not least because it corresponds to a pandemic response endowed with the extensive use of war-time analogies by state leadership across the world. The rhetoric of war calling for ‘extraordinary measures’ has found significantly increasingly footing in public discourse as the challenge on public healthcare institutions intensifies and political fault-lines lay exposed

Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde warned of the legitimisation of such ‘extreme measures’ that come from the construction of an issue as an ‘existential threat’, a process they termed ‘securitization'. While the threat from SARS-CoV-2 is very evident, the focus is on the risk posed to societal patterns from the proclamation of emergency measures and the departure from rules that would otherwise bind securitising actors or incumbents. As the cases examined here demonstrate, the securitization of the pandemic ‘endangering the nation state’ could potentially prove futile in flattening the curve and be fatal to democracy itself.

The outbreak was still a ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern’, when President Xi likened China’s fight against coronavirus to a ‘people’s war’. Invoking the nation’s faith in the leadership of the Communist Party of China, Wuhan was declared a 'hero' and plans for Chinese economic prowess, impervious. Even as the mask-clad commander of the people’s war visited hospitals and disease centres, the terminology made one reminiscent of propagandist Mao’s China. In the United States, Trump declared himself a 'war-time President' on March 18 and soon after, promulgated what has underwritten United States foreign policy for decades but never ever so loudly vocalised, that the office of the presidency has 'total authority'. Framing a public health crisis in military terms arguable enables the White House to shrug off responsibility, passing the buck to China instead. From the longest 2hour 24 minute coronavirus briefing to the latest #TrumpPressConference, speech acts have been labelled as propaganda and campaigning for the Presidency bid

March also witnessed a spectacle in South Africa. Complete with President Cyril Ramaphosa’s military regalia, the war against the invisible enemy was declared with a clear message that extraordinary measures wouldn’t be far off in the country, especially if orders are not abided. In Europe, on March 30, Fidesz-led Hungary signed away the remaining vestiges of democracy into legislation by granting Prime Minister Orbán an indefinite power to rule by decree, obligated due to the ‘emergency’. This ‘carte blanche to restrict human rights’ decimates civil liberties, oppositional power and press freedoms. The extreme control the new act grants, including the enactment or reconstruction of laws old and new with ‘de facto’ parliamentary support, especially in the absence of a sunset clause could upend the spirit of European democracy. Capitalising on coronavirus isn’t a tact limited to Hungary, Israel’s longest-serving Prime Minister, Netanyahu also instituted surveillance measures, incapacitated the Knesset and shut courts ahead of his own corruption trial. The looming constitutional crisis in Israel does not augur well for its democracy, just as it raises suspicion about the amended electoral rules in Poland. While the pandemic itself provides a strong campaign for the incumbent President Andrzej Duda, his opponents have been forced to forfeit hope on ‘online campaigning’ ahead of the May elections which remain unaffected by COVID-19, despite 77 percent Poles supporting a delay.

An unintended victim of coronavirus have been human rights as excessive measures leave indelible marks on fundamental freedoms around the world. Censorship of free speech in Thailand, restrictions of movement in Chile under a 'state of catastrophe' that leaves President Sebastián Piñera’s government in total charge and the complete dispersal of protests from Hong Kong, Iraq to India widens the chasm between the political elite and political will.

Political obedience and moral obligations to the state, and the consequences of contempt can’t be exempted if the war against coronavirus continues in its present shape. In South Asia, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina made this clear as she delineated the duties of the Bangladeshi citizen in this time of war, invoking the 1971 victory on March 25, the eve of the Independence and National Day 2020. There is an increasing fear of lasting authoritarianism as armies pour into quarantined cities and police brutality questions the government’s protection mandate. The cases of Kenya, Paraguay and the Philippines are the few documented ones in a very long list. Even though the novel coronavirus guises itself behind its invisibility, the ‘special responses’ to the war against it are very much tangible. The greatest threat to democracy at present is the fortification of impregnable power as dissent, especially against the government’s handling of the crisis becomes intolerable. In Maduro’s Venezuela, any criticism of the crumbling healthcare system is welcomed with crackdowns as countries establish a grey-line between dissent and rumour.

Myanmar’s government should immediately drop all criminal charges against three street artists arrested for painting a mural that raises awareness about the coronavirus pandemic. https://t.co/YHaYyTaoyz

— Georgie Bright (@georgie__bright) April 8, 2020

In Putin’s Russia, the ambit of what encompasses ‘fake news’ or ‘false information’ has been placed under Kremlin’s jurisdiction, the move being titled a ‘digital gulag’ by the Muscovite civil society. In an era of post-truth politics, coronavirus will displace industries of information just as the structural causes behind the worsening pandemic continue being shrouded behind the war narrative. Although the state has received a precedence in the war discourse, even wars against invisible enemies cannot be fought without actual armies.

"The second reasoning drawn out of the combative state discourse finds its underpinning in nationalism"

Nothing galvanises the nation more than a war at its doorstep. As the invisible enemy closes in, evocative speeches, historic metaphors and collective memory are summoned to demand ‘personal sacrifice’. The martyrdom ranges from working on the frontline and staying indoors, to living without basic means. While Britain designed ‘battle plans’, France went further to launch a military operation ‘Resilience’, even repatriating troops from the operation Chammal in Iraq to strength the French war defence against COVID-19. Coronavirus has qualified itself in situation rooms worldwide as ‘the greatest challenge since World War II’. The Americans are ready to act under the Defence Production Act, a legislation from the Korean War-era, as Brazil passed its ‘war budget’ declaring a state of emergency after much criticism for inaction. In a rarely used connotation, even the United Nations Secretary General designated the pandemic as a war, calling on multilateralism and the exigency of a war-time plan. The obvious implication of war however, is the absence of peacetime, a deviation from normalcy. The actions engendered by those empowered to choose them in the present state of affairs would define the fate of this pandemic and perhaps that of the future which follows. As Florian Bieber notes, even though the coronavirus is temporary, the entitlements and infringements it creates could be permanent.

The response to this unprecedented situation will be fashioned in history as a defining moment for nation-states, and the historical record would not deter from showing who emerged ‘victorious’. Given the national dependency on war-lexicon, the cliffhanger will be the implications of this war spirit on the future of International Relations. As internationalism is challenged by ideological factionalism, the triumphant would be a game-changer. Wars have often resulted in transformations of the world order, especially to institute checks and balances on power, would this war bear a similar consequence?

International human rights networks and watchdogs must keep wary of the lasting ramifications of war-time responses and extraordinary measures. While a new normal would emerge, it mustn’t mark a departure from fundamental negotiations with the state

Ultimately, the decisive factor will be the actual resources deployed to fight this war which exists in the national imagination. As the Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen writes, ‘tackling a social calamity is not like fighting a war which works best when a leader can use top-down power to order everyone to do what the leader wants’. Strong institutions and critical infrastructures redolent with the spirit of humanitarianism could not be more vital to the state-subject relationship that is under test by this pestilence. This enquiry into the impetus behind the declarations of war must be sustained until structural falterings don’t acquire the sphere of public debate. Truth be told, if a pre-emptive threat of war is enough to propel interminable arms race(s), one need not wait for a virus to better prepare their healthcare institutions for living populations

NOTE : All statistics regarding SARS-CoV-2 infections were noted at the time of authoring this piece and the author notes that these figures may vary drastically by the time of publication and reading. The standard tracker for references made here is by the Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine

This piece is original intellectual property of the author.

Neha Dewan

Neha is a non-Resident Fellow and Political Affairs Officer at Global Policy Insights. A specialist in International Security and Strategic Affairs, Neha holds an MPhil in International Relations and Politics from the University of Cambridge, a Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) in Political Science and a postgraduate diploma in Conflict Transformation and Peacebuilding from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, University of Delhi. She has also been actively engaged in working with different levels of the government, the civil society and youth, and has led several endeavors towards these efforts.

Recent Articles

- James Silverman ( Founder, U&I Global) interviews Arpit Chaturvedi (Co-founder and CEO, GPI) on AGENDA 2030- DO WE WANT IT? CENTRALISATION AND THE SDG’S

- Big Tech on Section 230 – Censorship or Disregard?

- Global Policy Insights (GPI) Annual India Colloquium.

- Antitrust hearing only a beginning on accountability

- The Commonwealth: Optimising Networks & Opportunities for the 21st Century

- Population Data in the Time of a Pandemic

- The Disconnect with Ground Realities

- Models to Make Vocational Training Work in India

- Comparing Health Care Systems in England, Taiwan, and the United States

- Commonwealth In Dialogue : Academic Series

- Are we rewarding fence-sitters and free-riders by relaxing penalties on CSR law violations?

- Changing Economic Models: From Mixed Economy to Liberalization, Privatization, and Globalization in India

- Goods and Services Tax (GST) – a Seventeen Year Ordeal to a Uniform Indirect Tax Regime in India

-

Commonwealth In Dialogue: International leader Series

Podcast: Patsy Robertson, Chair Ramphall institute in conversation with Uday Nagaraju, Executive President and Neha Dewan, Fellow & Researcher about Commonwealth - Creating a future-proof curriculum for the digital age

- Commonwealth In Dialogue: High Commissioner Series": H.E Dr. Asha-Rose Migiro

- High Commissioner of the United Republic of Tanzania to the United Kingdom & Republic of Ireland in conversation with Uday Nagaraju, Executive

- Commonwealth In Dialogue: Parliamentary Speaker Series

- Louisa Wall - Marriage Equality in New Zealand

- Hon An치lu Farrugia, Speaker of the House of Representatives Parliament of Malta & Secretary General CPA Small branches speaks to Uday Nagaraju, Executive President & Co-founder of Global Policy Insights on Commonwealth, CPA Small branches and Parliament of Malta

- Commonwealth Series: Cyprus High Commissioner to the UK H.E Euripides L Evriviades interviewed by Uday Nagaraju, Executive President Global Policy Insights & Neha Dewan, Fellow & Researcher

- Global Policycast: Ex-Minister of State in the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands- Victor Cummings interviewed by Arpit Chaturvedi, C.E.O Global Policy Insights.

- Global Policycast: Ex-Minister of Youth, Paraguay- Magali Caceres interviewed by Arpit Chaturvedi, C.E.O Global Policy Insights.

- Commonwealth Series: CPA Secretary-General Akbar Khan interviewed by Uday Nagaraju, Executive President Global Policy Insights & Divya Pamulaparthy

- The Perils of Decentralization and other Buzzwords in Governance and Policymaking