A Comparative Analysis of Key Structures & Responses to the Syrian Refugee Crisis in Germany, Turkey, and the United States

Posted On Fri, Jan 03, 2020 by Heather McIntyre,Jorge Contreras,Phung Nguyen under International Strategic Studies

Introduction

The world is facing an unprecedented trend of human displacement. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that there are 68.5 million forcibly displaced persons worldwide, of whom 25.4 million are refugees and 3.1 million are asylum seekers (UNHCR, 2018). Those persons classified as refugees “have been forced to flee [their] home because of war, violence, or persecution, often without warning” (International Rescue Committee, 2018). The scope of this paper will not permit analysis of all of the groups currently displaced by war, violence, or persecution. The authors of this project, however, believe that the realities faced by Syrian refugees and the magnitude of displacement experienced by this population in particular warrants further analysis.

To understand the events of the last eight years in Syria, it is beneficial to understand the history of the country since at least the 1940s. After gaining independence from France in 1946, a series of civilian and military governments alternated in power for many years, driven by both political and ethnic divisions (Syrian Civil War, 2019). In 1970, however, Ḥafiz al-Assad, a military officer and Syria’s then Secretary of Defense, successfully gained power in a coup and established the foundation of the authoritarian regime still in existence today (Syrian Civil War, 2019). His son, Bashar al-Asad, took control in 2000 amid hopes for democratic reforms in the country; his actions soon made it clear, however, that he had no intention of releasing the authoritarian grip placed on Syria by his father (Syrian Civil War, 2019). In March of 2011, frustration and discontentment with the Assad regime turned to violence in the country between numerous political and opposition groups (Humud, Blanchard, &Nikitin, 2019). By the summer of 2016, estimates placed the number of Syrians killed in what had come to be deemed a civil war at up to 400,000 (Byman& Speakman, 2016). As the conflict intensified, the number of actors attempting to intervene and/or influence the outcome of the war in their favor grew.

As is the case in war, those most vulnerable in the midst of this conflict are the civilians. According to a Congressional Research Service report that was updated in March of 2019, “...nearly 12 million people in Syria are in need of Humanitarian assistance, 6.2 million Syrians are internally displaced, and an additional 5.6 million Syrians are registered with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees as refugees in nearby countries” (Hamud et al., 2019, p.21). Where have Syrian refugees gone? A report published by the UNHCR in 2018 reports that 125 countries have granted them asylum (UNHCR, 2018).

This paper will examine the democratic structures and similarities and differences of responses to the crisis by three of those 125 countries. The first of these countries, Turkey, has been selected for study because of its proximity to the conflict and position as the home of most Syrian refugees. Many statements have been made regarding the “enormous strain” and impact of refugees on neighboring countries, and as Turkey is currently the host to the largest population of Syrian refugees, analysis of the recent and past democratic structures and systems it has in place to address, this strain is warranted (Ostrand, 2015). The second country selected for this comparative project was Germany. Though not to the same magnitude, Germany, like Turkey, is host to a significant number of Syrian refugees, approximately 500,000 as of 2017 (UNHCR, 2018). Unlike Turkey, however, its political structure is closer to that of a liberal democracy, making comparison of the two worthwhile. Finally, the third country selected for this analysis is the United States (U.S). The U.S. was chosen for its democratic similarity to Germany yet low number of Syrian refugee resettlements. Questions regarding how the structure of its systems may have played a part in these low resettlement numbers will be considered.

To better situate the political contexts of these countries, this paper will begin with a brief discussion of democracy before describing the specific democratic transitions and structures of the three countries. It will then discuss each country’s responses to the Syrian refugee crisis. This paper will culminate in an analysis of similarities and differences among the three countries’ approaches to the Syrian refugee crisis before providing recommendations and final thoughts regarding the tenuous state of democracy in our world today.

Democracy and Democratic Structures

This paper uses as a starting point the typology developed by Møller and Skaaning (2013) to select the three countries on which the authors will conduct an analysis of responses to the Syrian refugee crisis. Møller and Skaaning’s (2013) typology serves to “capture and systematize the most influential realistic definitions of democracy found in the literature” (p. 144). The typology’s most simplistic level – what the authors term “minimalist democracy” – is based on Joseph A. Schumpeter’s minimalist definition of democracy as simply entailing competitive elections for political power through free elections. The next level up – “electoral democracy” – expands on elections with the addition of equal and universal suffrage and high levels of electoral integrity. Robert A. Dahl’s concept of “polyarchies” is then provided, where, in addition to competitive elections and inclusive elections with high integrity, there is the presence of civil liberties (i.e., freedom of expression, association, and assembly). Democracies, as envisioned by Dahl, are political systems where citizens are able “(1) to formulate their preferences; (2) to signify their preferences to their fellow citizens and the government; and (3) to have their preferences weighed equally in the conduct of government” (Ishiyama, 2012, p. 28). As this is an ideal, Dahl coined the concept of “polyarchy” to describe “non-ideal” democracies that exist in the real world (Ishiyama, 2012). Lastly, the typology builds to Guillermo O’Donnell’s addition of the rule of law to polyarchies, whereby laws are equally applied to all, be they citizen or ruler. This most expansive concept of democracy the authors have termed “liberal democracy.” Table 1 below shows Møller and Skaaning’s typology of the democratic political regimes.

Table 1, A typology of democratic political regimes (Møller and Skaaning, 2013, p. 144)

| Competitive Elections | Inclusive Elections with High Integrity | Civil Liberties | Rule of Law | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimalist Democracy | + | |||

| Electoral Democracy | + | + | ||

| Polyarchy | + | + | + | |

| Liberal Democracy | + | + | + | + |

Elements within democratic systems of course encompass more than the four basic elements in Møller and Skaaning’s (2013) typology. Appendix 1 describes in detail whether the countries chosen in this project – the United States, Germany, and Turkey – adhere to the nine rules of democracy, as gathered by Dahl (1982) and Schmitter& Karl (1991).

In describing the process through which countries experience a democratic transition, Ishiyama (2012) identifies three elements that may explain the “painlessness” of democratization: 1) the extent to which the principle of accountability (where governors are responsible to others for their political actions) and rule of law were established prior to industrialization; 2) the extent to which a mass national identity was established prior to industrialization; and 3) the extent to which the old social order was swept away before industrialization (p. 33). The experience of industrialization is important, as Ishiyama (2012) considers it to be “a disruptive force which unleashes new social forces that can overwhelm existing political systems” (p. 30). This paper will attempt to adopt Ishiyama’s (2012) framework in looking at the democratic transitions of our three countries.

Ishiyama (2012) suggests that there is a temptation to think of democracy as an inevitability. However, in his research of the democratization of six different countries, he reminds us that it is through the coinciding of both “long-term trends” and “short-term institutional choices” (Ishiyama, 2012, p. 27) that democracies occur; citing Giovanni Sartori (1968), he writes, “we often forget in most countries in Europe, democracy did not just ‘emerge,’ but was in fact the product of human choices made at critical moments in time” (p. 27). Thus, it is through intentional, conscientious effort that democratic regimes are created. Just as it is through conscientious effort that democracies occur, it is through conscientious effort that democracies are maintained. In all three countries, democracy is currently in a tenuous place, with Freedom House (2019a) assessing some declines to the democracy of all three countries, due partially to the presence of the very migrants about whom we write in this paper.

The Democratic System of the U.S.

Following Møller and Skaaning’s (2013) typology of democratic political regimes, the democratic system practiced in the United States can be defined as a liberal democracy. Freedom House (2019d) describes the U.S. as “arguably the world’s oldest existing democracy,” though democratization was not without violence or turbulence. Some elements of Ishiyama’s (2012) framework were already sewn into the cultural fabric of the United States prior to industrialization: the principle of accountability “had long been a part of the political tradition in the thirteen colonies… and was a centerpiece in the justification for the War of Independence against Great Britain” (p. 44), while institutions and mechanisms of political participation were also already in place prior to industrial expansion in the nineteenth century. However, the country’s young age meant it did not have an established mass national identity, with citizens identifying more closely with their state identity than their national identity. Socioeconomic divisions also existed as the country was divided into three distinct regions: “a cotton-producing South; a food-producing West made of free farmers; and a rapidly industrializing Northeast” (Ishiyama, 2012, p. 44). It was not until after a “tremendously violent” (Ishiyama, 2012, p. 46) civil war between the South and allied West and Northeast that a centralized unified state, and with it a sense of national American identity, were developed.

While the United States has traditionally been viewed as a global democratic leader, Freedom House warns that the U.S.’s democratic institutions have been in decline over the past thirteen years, due to political polarization, declining economic mobility, the influence of special interests, diminished influence of fact-based reporting in favor of partisan media, and the infringement of citizens’ rights through George W. Bush’s surveillance program and Barack Obama’s crackdown on press leaks (2019a, p. 17). However, democracy has particularly been threatened under the current presidential administration. In assessing President Trump’s attitudes towards the U.S. constitutional system, Freedom House states that “no president in living memory has shown less respect for it tenets, norms, and principles” (2019a, p. 17). With its declines in the rule of law, conduct of elections, and safeguards against corruption (p. 19), Freedom House (2019a) assesses that the U.S. currently is closer to struggling democracies like Croatia than traditional counterparts like Germany and the United Kingdom.

The Democratic System of Germany

Like the United States, Germany is a liberal democracy following Møller and Skaaning’s (2013) typology. Unlike the United States, which is a presidential republic, with the president serving as both head of state and head of government (Freedom House, 2019d), Germany is a parliamentary and federal democracy, where citizens vote for representatives in the Bundestag (Federal Parliament), who then elect top leadership: the President and Federal Chancellor. The President is chosen by the Federal Convention, a body formed jointly by the Bundestag and state representatives (Freedom House, 2019b) and serves a largely ceremonial role, while the Federal Chancellor, elected by the Bundestag, serves as the Head of the Government. Former foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier has served as President since 2017, while Angela Merkel has served as Chancellor since 2005.

Germany is a country described by Hindy (2018) as having “a historic image to shed.” Its history of attempts to democratize was turbulent. Well into the modern era, Germany was marked by political and national disunity, thereby lacking the crucial element of a mass national identity integral to Ishiyama’s (2012) framework. Germany’s first attempt at democratization occurred after World War I with the Weimar Republic in 1919 during a time of economic instability and a fractured national identity. The country’s economy collapsed during the Weimar years, which provided fertile ground for ideological polarization and political instability and led to the rise of Nazism and Hitler, who promised to “restore the honor of the German people and rectify the wrongs and injustices imposed upon Germany by the Treaty of Versailles” (Ishiyama, 2012, p. 51). Democracy was later imposed by the Allies following World War II.

Germany’s political system is strongly influenced by its totalitarian past. Laws are built into Germany’s Constitution, called the “Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany,” to prevent the re-emergence of authoritarian rule; as Schultheis (2019) summarizes: Germany’s “constitution and institutions are designed with the underlying goal of preventing another Nazi regime.” The country even tolerates limitations of freedoms to some extent to prevent the rise of extremism, particularly on the right. For instance, restrictions on hate speech, which can range from incitement of violence to statements about specific religions, are stronger in Germany than in many other Western countries, and extremist groups can not only be monitored but even banned under the German constitution (Schultheis, 2019). The country’s need to make penance for its historical wrongdoings is arguably a key element of its societal and political culture and an important architect of the country’s mental model. However, there has been a recent rise in anti-immigrant sentiment and far-right ideology. 2017 saw the rise of the far-right nationalist political party, Alternative for Germany (AfD), which was supported by more than five million people in the 2017 federal elections and earned 12.6% of the vote nationally and more than 90 seats in the Bundestag (Freedom House, 2019b). In August and September 2018, anti-immigrant protests in the city of Chemnitz turned violent when far-right demonstrators attacked and harassed people they perceived to be immigrants (Freedom House, 2019b). Taub & Fisher (2018) suggest that increases in anti-immigrant sentiments stem from broader anxieties about social change, with people becoming more attached to their ethnic and national identities when they feel a sense of threat or loss of control. Migrants and asylum seekers are also perceived as symbols of the political establishment’s failure to protect the interests of its citizens. It is perhaps due to the perception of a lack of shared national identity in an increasingly globalized world and of failure of leaders to adhere to the principles of accountability, two elements of Ishiyama’s (2012) framework of conditions for democratization, that is causing turbulence in Germany’s political state.

The Democratic System of Turkey

Modern Turkey was founded in 1923 from the remnants of the Ottoman Empire following World War I. The Ottoman Empire had joined WWI on the side of Germany; after Germany’s loss, the empire was dismantled, with Turkey remaining under the rule of the sultan while Greece occupied cities in western Turkey. Mustafa Kemal, a member of a group of military men called the Young Turks who vehemently opposed the rule of the sultan and supported modern Western democracies, helped to drive the Greeks from Turkish soil after rallying Turkish patriots. In 1919, Kemal supported a national pact to create a new Turkish nation and was recognized in 1922 as the legitimate leader of Turkey by European powers, which prompted the sultan to flee the country. The following year, Kemal proclaimed the Republic of Turkey, with himself as president. A year later, Kemal produced a constitution and endeavored to transform Turkey into a secular, Western-style democracy. He eventually renamed himself “Ataturk,” meaning “Father of the Turks.” (Turkey: An evolving democracy, n.d.)

In assessing Turkey’s democratization with Ishiyama’s (2012) framework, we do see that all three conditions are satisfied: the loss of the monarchy (in this case, the sultan) established the principle of accountability, while the creation of the Republic of Turkey, described by Columbia (1994) as a “new homogeneous nation-state that stood in sharp contrast to the multi-ethnic Ottoman Empire out of whose ashes it arose” under Ataturk, “the Father of the Turks,” helped to establish a mass national identity. The dismantling of the Ottoman Empire and imposition of democratic practices also broadly swept out the old social order, the last condition of Ishiyama’s (2012) framework, resulting in a relatively smooth democratic transition.

According to Møller and Skaaning’s (2013) typology, Turkey is an electoral democracy, observing competitive elections with high integrity and universal suffrage, though with deficiencies in the rule of law. However, much has changed since Møller and Skaaning’s article was published in 2013. In recent years, the country has become increasingly authoritarian under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. When Erdogan was first elected in 2002, there were high hopes in the West about progress made on democratic governance, minority rights, and economic reform. There was even interest in bringing Turkey into the European Union, due to its strategic geographical importance and economic potential, culminating in negotiations in October 2005 (Kirişci&Sloat, 2019). Goodman (2018) suggests that Erdogan’s “early democratic reforms and assertion of civilian control over the military were largely about winning the welcome of the European bloc.” However, lack of action on the part of the EU, and French Prime Nicolas Sarkozy’s and German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s preference that Turkey be given a “privileged position” instead of actual membership into the EU was insulting. Equally insulting was the EU’s failure to understand an attempted coup in 2016 and to show immediate solidarity with Turkey’s democratically elected leadership, prompting Erdogan to adopt an anti-EU attitude and to forgo pursuit of EU membership (Kirişci&Sloat, 2019).

Since the 2016 attempted coup, the authoritarian nature of Erdogan’s government has been fully consolidated. In 2017, Turkish citizens voted in a constitutional referendum on a package of measures that shifted the political system from a Parliamentary system to a centralized Presidential system, thereby concentrating Erdogan’s power. The reforms eliminated the role of prime minister and provided to the president new powers, including “the right to issue decrees, propose the national budget, appoint cabinet ministers and high-level bureaucrats without a confidence vote from parliament, and appointment more than half of the members of the high courts” (Kirişci&Sloat, 2019, p. 3). There are concerns about insufficient checks and balances, given the immense concentration of power in one office, limited parliamentary oversight, and a “weakening of judicial independence” (Kirişci&Sloat, 2019, p. 3). Erosions of civil liberties also continue, with arrests and convictions of journalists and social media users critical of the government, as well as tight restrictions on assembly and union rights (Freedom House, 2019c). The centralized power in the new Presidential system in Turkey further entrenches Erdogan’s power (Kirişci&Toygür, 2019).

Responses to the Syrian Refugee Crisis

The United States

Key stakeholders seem to suggest that, on the whole, the United States has been and is a friend to refugees and open to their permanent resettlement within its borders. The U.S. Department of State, for example, boasts that the country has resettled over 3 million refugees since 1980 (U.S. Department of State, n.d.). Indeed, after World War II, provisions were made for the resettlement of approximately 650,000 refugees from Europe (Office of Refugee Resettlement, n.d.). As will be discussed later in this section, though, current political posturing and policy agendas would seem to challenge the assumption that such sentiments remain in the current administration.

Prior to 1980, there was not a standardized program or pathway for refugees to enter the United States. It was only with the signing of the Refugee Act of 1980 by President Jimmy Carter that the ad hoc nature of refugee legislation changed, and the “permanent [procedure] for vetting, admitting, and resettling refugees into the country” that is still in place today was established (Felter& McBride, 2018). Particularly relevant in relation to the Syrian refugee crisis and the U.S. government’s response to it were the powers vested to the Executive Branch of the U.S. government under this act. The 1980 legislation did not set a standing resettlement quota. Instead, in consultation with Congress, it is the President who sets the number of refugees slots available each year (Cepla, 2019).

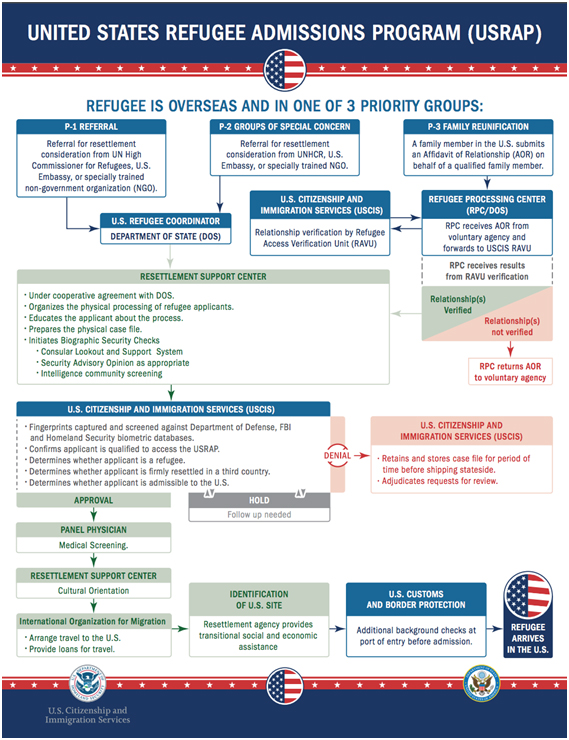

The United States Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) itself is complex, incorporating multiple government agencies & programs, sub-bureaus, intergovernmental organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGO), and other 501(c)3 organizations. If a Syrian refugee were to seek resettlement in the United States, the first hurdle they would have to cross would be meeting a few key parameters. The Department of State acknowledges that resettlement is “the solution for only a few” refugees, persons defined as those “who [have] fled from [their] home country and cannot return because [they have] a well-founded fear of persecution based on religion, race, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group” (U.S. Department of State, n.d). If that criteria is met, and the person does not have any family members already living in the United States, then they must gain a referral from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), a U.S. embassy, or, in some instances, an NGO (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, n.d). Space will not permit a further detailed accounting of all of the necessary steps from referral to resettlement, but it is worth mentioning that the refugee will come into contact with no less than the U.S. Department of State, Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Health and Human Services and some of their sub-bureaus and contractors. The authors have included a flowchart published by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services in Appendix 2 of this paper for further reference.

The U.S. government’s response to the refugee crisis can at times be baffling. Thus, this section will seek to unravel some of the puzzle by exploring four perspectives relevant to the government’s policy and implementation decisions. The perspectives are as follows: politics, national security/counter-terrorism, vulnerable populations, and the U.S.’s responsibility to the global community.

From a political perspective, the resettlement quota is vulnerable to shifts in national and international politics. As mentioned previously, it is the President who sets the ceiling for the number of refugees the country will resettle each year. Under the Obama Administration, the quota was set at 80,000 for 2016, but was eventually increased by 5,000 in response to the Syrian crisis (Felter& McBride, 2018). Since that time, and with the transfer of power to the Trump Administration, the quota has steadily declined to 30,000 for 2019, the lowest cap since the beginning of the USRAP in 1980 (Felter& McBride, 2018). To understand why the quota has decreased so significantly in the past three years, national security & counter-terrorism must now be added to the mix of perspectives.

In November 2015, terrorists killed 130 people and wounded 494 in Paris, France (2015 Paris Terror Attacks, 2018). Circumstances involving some of the terrorists sparked fear and a backlash against the resettlement of refugees, particularly those from Syria. As reported by BBC, two men identified as “Ahmad al-Mohammad” and “M al-Mahmod,” likely posed as Syrian refugees and “came to Europe with migrants via the Greek island of Leros” (Paris attacks, 2016). Once this information was published, Governors from a majority of U.S. states decried the resettlement of Syrian refugees in their states amid fears about the robustness of security screening processes and the ability of terrorists to pose as refugees (Felter& McBride, 2018).

The full effects of this outcry were realized when President Trump was inaugurated in 2017. Not only was the resettlement quota for the year reduced, but within seven days of taking office, he signed Executive Order #13769, which prohibited persons from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen from entering the U.S. (Felter& McBride, 2018). Of consequence for the crisis in question, it “also indefinitely barred all Syrian refugees” (Felter& McBride, 2018). Though this Executive Order was met with fierce debate and rebuke by some, the Supreme Court ultimately allowed a new iteration of the order (#13780) to stand, and it took effect in June 2018 (Cepla, 2019). Since that time, very few refugees from Syria have been resettled.

The current administration, however, does not believe that they have neglected vulnerable Syrians nor their responsibility to the global community to share the burden of this crisis. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has sought to draw attention away from the dwindling resettlement ceiling to the amount of humanitarian aid given by the U.S. to the Syrian crisis, an amount that is estimated at $9.5 billion (Zezima, 2019). Though this is a significant amount of humanitarian aid, the administration’s current policies have affected the capacity of US Refugee Admissions Program’s domestic resettlement partners to resettle refugees no matter their country of origin, raising questions about the long-term consequences on the resettlement system’s capacity (Zezima, 2019). With the decreased cap, their funding has also decreased, the current pace of resettlement of refugees in the United States is not on pace to reach the cap of 30,000 (Cepla, 2019).

Germany

When the large influx of migrants first emerged in Europe in 2015, Germany was hailed the “epitome of a liberal, compassionate approach to migration” (Vonberg, 2018) after German Chancellor Angela Merkel famously declared “We can do it!” to rally her country in support of refugees (Livingstone, 2016). Under Merkel’s leadership, the German government decided to suspend European asylum rules and allow tens of thousands of refugees stranded in Hungary to enter Germany through Austria (Ostrand, 2015). Since 2015, Germany has received more than 1.5 million asylum applications, almost half of the total applications across the European bloc (Vonberg, 2018). Specifically, with regard to applicants from Syria, Germany has prioritized review of Syrian asylum applications and approved a greater share of Syrians over non-Syrians (Connor, 2017). In 2015, Germany also temporarily halted the Dublin Regulation for Syrians, allowing officials to process Syrian applicants’ asylum claims regardless of where they entered (AIDA, 2019a). Today, more than 700,000 Syrians are spread out among Germany’s 82 million inhabitants (Hindy, 2018). Though the country has since enacted stricter border restrictions, in May 2019, Germany’s Interior Minister confirmed that the country would continue to provide refuge to Syrian asylum-seekers after assessing that the country is still unsafe (DW, 2019).

Why did Germany welcome refugees?

Speculation has been made about Germany’s unique history and culture to explain its welcoming of migrants. Hindy (2018) describes Germany as having a “historic image to shed” and suggests that many of its laws have been established to compensate for its past political atrocities. Mayers (2015) explains that “the right to asylum was first guaranteed by Germany’s Basic Law in 1948 as a direct reaction to the Holocaust” and boldly states that “since the introduction of the Basic Law, Germany has prided itself on being a safe haven for those in need” (p. 1). The country’s need to atone for the historical atrocity of the Holocaust arguably informs its cultural and political mental model.

Under the Dublin Regulation, the first European member state where asylum seekers enter and where they are processed is responsible for handling the applicant’s claim. EU countries can therefore send refugees back to the first EU country the applicant entered in order to have their claims considered. The Dublin Regulation is controversial, as it places the onus of handling the vast majority of EU asylum claims on just a handful of southern and eastern European countries (The Local, 2019). As of 2019, there is no longer any distinction made between Syrians and other nationals in Germany (AIDA, 2019a).

While there are humanitarian motivators behind Germany’s decision to welcome refugees, there are also tangible economic benefits to welcoming migrants. Germany has an ageing population and a shortage of skilled technical workers (Witte & Beck, 2019). As low unemployment numbers are pushing young Germans from wanting to pursue trade work, the country finds itself in need of skilled workers. According to Wolfgang Kaschuba, the former director of the Berlin Institute for Empirical Integration and Migration Research, Germany needs about half a million migrants every year in order to maintain its economic well-being (Witte & Beck, 2019).

Overview of the asylum process and stakeholders involved

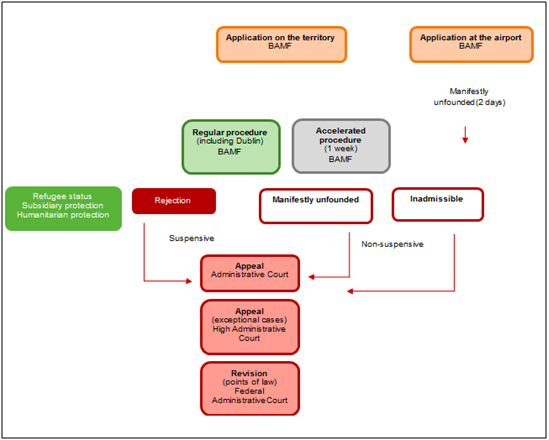

As mentioned earlier, migrants attempting to enter Germany who were first processed by another EU state are subject to being returned to their country of entry under the Dublin Regulation. In 2015, Germany temporarily suspended this law to accommodate Syrian refugees, though a distinction is no longer made between Syrians and other nationals. Figure 1below, provided by the Asylum Information Database (2019b), shows the steps and offices involved in processing asylum applications.

Figure 1

Source: the Asylum Information Database (2019b)

Overview of asylum application processing in Germany

A number of actors and departments play a role in the processing of applications and support of asylum applicants. The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (known by its German acronym, BAMF) serves as the first point of official contact for all refugees. The office processes asylum applications and administers asylum, welfare, and unemployment benefits. State and local governments maintain initial reception centers and administers health care, education, and housing needs. Support from volunteers and civil society also plays a role in filling gaps to make sure daily needs are met, though this level of support varies across the state. Berlin in particular has strong networks of settled migrants volunteering their support to assist newcomers (Hindy, 2018).

Integration efforts

The German government has been thoughtful in its development of programs and services to accommodate newly-arrived refugees, efforts that were informed by the country’s past experiences with Turkish migrant workers in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1961, facing a labor shortage, the country signed a contract with Turkey to bring in hundreds of thousands of guest workers. However, only limited consideration was given to creating support networks for these migrant workers, as the country assumed that they would leave. Instead, many Turks stayed and brought their families. As a result of this lack of integration efforts, Turks remain clustered in neighborhoods. Today, the 2.5 million people of Turkish descent in Germany are considered the least integrated minority in the country, with unemployment around 16 percent (Hindy, 2018).

To avoid such a fate with Syrian migrants, the government has intentionally attempted to “fairly distribute” all refugees through Germany’s sixteen states and has provided services with thoughtful foresight and planning. Syrian children with asylum status are eligible for free government-provided schooling, while the government runs “integration courses” for many teenage and adult refugees to provide German language instruction and modules about the country’s laws, history, and cultural norms (Hindy, 2018). 400,000 refugees are also working or participating in a job training program, with 44,000 refugees enrolled in Germany’s renowned apprenticeship programs (Witte & Beck, 2019). A fixture of Germany’s economy, the apprenticeship program has increasingly fallen out of favor with young Germans, who have lost interest in vocational training and are more interested in pursuing a university education due to the country’s low unemployment numbers. Refugees have been filling in this gap and providing the necessary skilled labor needed to maintain the economy. Though it may still be too early to know the economic gains of refugee participation in these apprenticeship programs, a recent Washington Post article published earlier this month states that Germany is beginning to “reap some gains,” with participation in these programs on pace with, or even ahead of, experts’ predictions (Witte & Beck, 2019).

Increased border restrictions and the impact of migrants on German politics

Border restrictions have increased since 2015 and the number of people seeking asylum in Germany has plummeted from 722,000 in 2016 to 198,000 the following year (Vonberg, 2018). ). Although Hindy (2018) states that research suggests Germany’s efforts at integrating refugees has been “a success,” given that “fears that refugees would spur an increase in terrorism proved unwarranted… [as] did worries that the refugee influx would derail Germany’s economy,” the presence of refugees has brought to the surface some latent racial anxiety about the country’s rising refugee population. This has been demonstrated through the emergence of the far-right, anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the Chemnitz incident of August 28, 2018, where a crowd of 6,000 Germans took to the streets to rally violence against perceived foreigners following the death of a 35-year-old German citizen of stab wounds after a fight with a Syrian and an Iraqi man (Witte & Beck, 2018).

While German Chancellor Angela Merkel was initially heralded the “Refugee Chancellor” (Vonberg, 2018), praised for her “defiant decency” (Gerson, 2015), and named Time magazine’s Person of the Year in 2015 for her commitment to open borders (Vick, 2015), even sparring openly with her Interior Minister over the Austrian border (Fischer &Bennhold, 2018). Although her political capital and authority arguably suffered for this decision. In 2017, Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union, saw heavy losses in the federal elections, while the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party entered the Bundestag for the first time and earned 12.6% of the vote nationally (Freedom House, 2018). Merkel saw these election results as a “clear sign that things can’t go on as they are” (Le Blond, 2018) and announced that she planned to step down as party leader at the end of 2018 and would not seek another term as Chancellor in 2021, leaving politics completely after that date. Le Blond (2018) summarizes that “the subsequent arrival of more than one million asylum seekers left the country deeply polarised [sic] and fuelled [sic] the rise of the far-right.”

Turkey

With an estimated 3.5 million Syrian refugeesin Turkey (UNHCR, 2018), Turkey has emerged as the home of the world’s largest refugee population in recent years, a distinction the country has held for eight consecutive years. Turkey shares a 500-mile-long border with Syria and became a safe haven for Syrians soon after the conflict began. Although Turkey was already home to the largest population of refugees from Afghanistan prior to the Syrian refugee crisis (UNHCR, 2017), historically, Turkey’s immigration wastacit at best. However, robust and organized asylum protocol wasintroduced in recent years. Turkey’s response to the Syrian refugee crisis is rooted in its practice of favoring kinship-based immigration policies and external ambitions. Scholars like Ahmet İçduygu from the Migration Policy Institute and others have described Turkey’s open-door asylum process as “generous” (2015) and a policy rooted in a nation-building ethos molded by the kinship asylum practices that dominated the Republic of Turkey soon after it was created in the 1920s. In the simplest terms, kinship policies aimed to create favorable policies for certain ethnic groups in the region. However, immigration policies that favored some and not others were recently curbed by the introduction of the 2013 Comprehensive Law on Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP).

In 2011, as the Syrian crisis emerged, Turkey’s ambition to join the EU led the country to pursue policies that match EU standards. The adoption of the LFIP in 2013 not only set the legal framework for asylum, it also reiterated Turkey’s obligations towards “all persons in need of international protection,” regardless of country of origin (AIDA, 2019c). Critically, the LFIP defined a Temporary Protection (TP) rule for the Syrian refugees (İçduygu, 2015; World Bank, 2015). The law establishes how temporary protection status is issued and the specific provisions for admission, registration, and exit while under temporary protection in Turkey. Just as important, LFIP outlined the rights and responsibilities of those under temporary protection and the coordination between national, local, and international agencies involved in the response (World Bank, 2015). A fundamental cog the LFIP created was the Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) agency (AIDA, 2019c), Turkey’s migration and asylum catch-all agency.

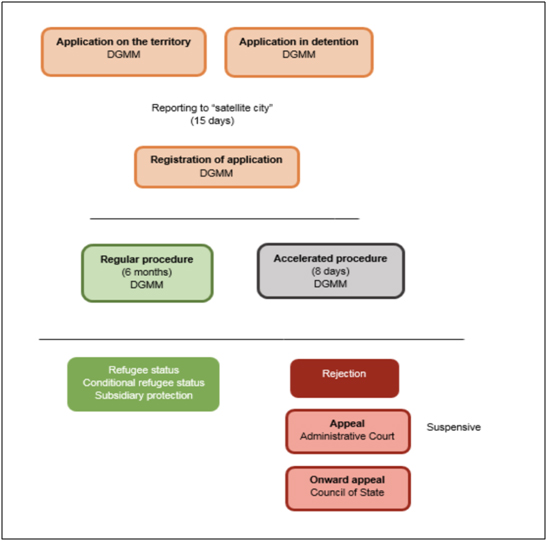

Overview of the asylum process and stakeholders involved

As Turkey’s immigration agency, the DGMM operates two separate asylum processes. The first process is designed specifically to address the large number of asylum seekers from Syria; the second is meant for any other asylum seeker from any other countries of origin. Figure 3 below, designed by the Asylum Information Database (2019c), illustrates the steps involved in the dual processing systems in Turkey. While Syrian asylum seekers are granted temporary status almost immediately, asylum seekers from other countries of origin are subject to a status determination procedure conducted by DGMM (AIDA, 2019c).

Figure 2, Asylum processing systems in Turkey

Source: the Asylum Information Database (2019c)

Decentralization

To execute the Law on Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP) guidelines, and to respond to the various needs of 3.5 million Syrians, the Turkish government decentralized authority to create subsidiary legal entities or ministries. The Turkish ministries coordinate an extensive cross-sector network of government agencies. For example, according to the World Bank (2015), the AFAD, Turkey’s Disaster and Emergency Management Authority, coordinates efforts with at least ten Turkish government ministries or departments, including the Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Turkish Armed Forces, and the Presidency of Religious Affairs, to name a few.

Turkey’s response to the crisis also includes international NGOs and Turkish civil society. Although Turkey has taken on the brunt of the cost of operating the refugee camps and supporting the displaced Syrians with public support and services, the non-public sector has provided Turkey with various forms of support. One example is the technical support Turkey received from members of the international community to build the DGMM’s ability to manage a new tracking system. The Turkish public for their part have also provided individual support for the Syrian refugees. Although studies suggest sentiments towards the refugees have started to sour, in 2014, acts of kindness and support for the recently displaced were common. A survey from 2014 across a large sample in 18 provinces indicated that 31 percent of Turkish respondents had made a personal financial contribution in support of Syrian refugees (HUGO, 2014).

Tension

Although Syrians fleeing the conflict received overwhelming support from the Turkish government and public during the initial stages of the war, support has waned as the conflict became protracted. . In a survey from the German Marshall Fund (2015), 81% of Turkish respondents reported they “do not think Syrian immigrants integrate well.” Furthermore, Kirişci (2019) from the Brookings Institute recently referenced a “Syrians Barometer-2017” poll to reveal a large segment of the Turkish public resent Syrian refugees. The tired old perceptions of deteriorating public services, cost of living increases, and rising unemployment are understood to be the reasons for the resentment. However, other surveys suggest a majority of Syrians think they are well treated by their Turkish hosts, with two thirds (66%) in Gaziantep reporting having a good or very good relationship with their host community (World Bank, 2015, pg. 9)

Types of placements

Turkey’s response to the Syrian refugee crisis was somewhat unique. Not only did the Turkish government choose to finance the campaign themselves - a choice that by 2015 had a price tag of an estimated $5-7 billion (İçduygu, 2015; World Bank, 2015); it also implemented an approach that allowed Syrians to live and work in urban cities. Although some Syrian refugees in Turkey opted to live in camps, the majority found themselves in urban communities.

The Camp Approach

First, the Turkish government took the approach of limiting the number of Syrian refugees in camps. Each camp was staffed and managed exclusively by the Turkish government through the country’s Disaster and Emergency Management Authority, known as AFAD (World Bank, 2015). Although the AFAD utilized UNHCR guidelines on refugee camps, Turkey took the unorthodox step of designing its own approach. For example, refugees living in a camp have access to a Syrian teacher, electronic food vouchers (e-cards), and the ability to elect their own camp representative during camp management meetings (World Bank, 2015). Although not perfect, a 2015 UNHCR report found that the camps operated by the Turkish government met the organization’s standards.

The Non-Camp Approach

A unique element in the refugee landscape in Turkey is the sheer number of Syrians living in urban communities. While emerging evidence shows the benefits to the host country when policies allow for refugees to live outside a camp setting and refugees actively participate in their host country’s society (UNHCR, 2014), the non-camp approach was driven by the scale of the Syrian crisis. Initially, only Syrians with existing social, cultural, or economic networks in Turkey were placed in familial homes. However, this practice changed as the conflict in Syria became protracted and a return to home seemed unlikely. As the conflict persisted, Syrians began to branch out and secure their own places to live (Ozden, 2013).

Analysis of Similarities and Differences

Up to this point, a great deal of space has been dedicated to describing the Turkish, American, and German systems in detail and possible reasons why each country has responded to the Syrian refugee crisis the way it has. The following section will seek to synthesize this information by breaking down similarities and differences among the systems.

Similarities Between the U.S. & German Systems as Compared to Turkey

Proximity to the crisis has been one of the key determinants to response to this crisis. Both the German and American response was built upon threads of idealism. Turkey’s, however, was out of necessity. Further, the response to the crisis in the U.S. and Germany has been spearheaded by their respective heads of state. Due to the structure of the U.S. refugee admissions program, Presidents Obama and Trump have been instrumental in setting the tone and direction the United States has taken with initial increases and then decreases to the quota for resettlement. Similarly, Chancellor Angela Merkel ignited Germany’s open-door policy. It was the Turkish parliament, however, that passed legislation allowing for protections of the refugees flooding its borders.

Similarities Between the U.S. & Turkish Systems

As conservative voices have grown in both countries, policies in both Turkey and the U.S. have shifted away from resettlement toward encouraging refugees to return to Syria. President Trump has done this by reducing the resettlement cap to its lowest since the implementation of the modern refugee resettlement program and funneling resources through humanitarian aid. Meanwhile, Turkey has closed its border to new refugees, with President Erdogan actively seeking “...to facilitate the return home of all [Turkey’s] guests” (O’Toole, 2018).

Similarities Between the German & Turkish Systems

At the beginning of the crisis, both Germany and Turkey opened their doors broadly to refugees fleeing conflict in Syria. As the clarity of a return timeline became uncertain for the displaced, each country’s welcome from policy makers and citizens has waned. This is illustrated by the German Marshall Fund that found 81% of Turkish respondents reported they “do not think Syrian immigrants integrate well” (2015) and the rise of the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany (AfD) political party in the European nation.

Differences Between the U.S. & German Systems

The historical perspectives that influence the U.S. and German systems have played a significant role in their willingness to accept refugees. As discussed in prior sections, Germany’s response is a result of introspection of its history of Nazism, which has left it with a desire to prove itself reformed and a protector of the vulnerable.The response of the United States has been extrinsically motivated, however, with the country doing just enough to meet a threshold of contribution as one of the players in international movements for human rights and protections.

Additionally, it is likely that cultural attitudes about assistance have played a role in the integration programs that exist in both countries. The American “bootstraps” mental model means that assistance from the government for refugee resettlement is short lived, as they are expected to quickly find and hold a job, pay back travel loans from the government, and pull themselves up by their own means. Germany, however, having learned from its prior experiences in the 1960s and 1970s with Turkish migrants, takes a much more supportive role, offering apprenticeships, intensive language training, and then jobs.

Conclusions

With 25.4 million refugees and 3.1 million asylum seekers (UNHCR, 2018), the world is facing an unprecedented trend of human displacement. The humanitarian need calls for a critical review and examination of how response efforts are being carried out by different countries. Our study examined the democratic structures and responses of three of the 125 nations responding to the Syrian refugee crisis.

While both the United States and Germany are liberal democracies, we found that the German government’s thoughtful development of programs and services to accommodate newly-arrived refugees stem from their country’s past experiences with Turkish migrant workers in the 1960s and 1970s and the country’s need to make penance for its historical wrongdoings. Learning from their experiences in the 1960s and1970s influenced Germany’s policy to offer displaced Syrians a variety of support services, including free government-provided schooling and integration courses. Both the United States and Turkey could benefit from adopting similar comprehensive integration models. Introducing integration practices in both Turkey and the United States require concerted efforts to stay the course towards democratic principles.

Taub & Fisher (2018) infer that anti-immigrant sentiments stem from broader anxieties about social change, that people increase their attachment to their ethnic and national identities when they feel a sense of threat or loss of control. As we have discovered, in recent years, Germany, Turkey, and United States have experienced an increase in anti-immigrant sentiment, tied closely to the recent surge in Syrian refugees. This rise of anti-immigrant sentiment has led to the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) political party in Germany, a successful U.S. presidential campaign of a man who openly ridiculed and scorned the country’s immigration policy, and a shift in Turkey’s open-door or kinship immigration model.

The social and political “strain” caused by the Syrian refugees in each of the three countries, regardless of democratic typology, is clear. However, as Ishiyama (2012) warns us, as active members of our civil society, we cannot fall prey to the lure of thinking of democracy as an inevitability Ishiyama poignantly cited the work of Giovanni Sartori (1968) to remind us that democracy did not simply emerge; instead, it was “a product of human choices made at critical moments in time” (2012, p. 27). Germany, Turkey, and the United States, are all products of human choices made during critical points of inflection. A review of the historical context of each country supports the claim that there is a clear relationship between both “long-term trends” and “short-term institutional choices” (Ishiyama, 2012, p. 27), or as the old proverb asserts, “as the twig is bent, so grows the tree.” Facing an unprecedented trend of human displacement, the global community needs to ensure services and commitments are consistently bent in favor of those in most need.

Appendix 1.

Nine Rules to Democracy (Dahl, 1982; Schmitter& Karl, 1991)

| Rule | United States | Germany | Turkey |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Control over government decisions about policy is constitutionally vested in elected officials | Control over government decisions about policy is constitutionally vested in elected officials. However, Freedom House (2019d) reports that Congress has struggled to perform its various duties in recent years, particularly with drafting and passing the government’s annual appropriations bills, due to partisan infighting and polarization. | Democratically elected representatives decide and implement policy without undue interference. (Freedom House, 2019b) | Citizens voted in a 2017 constitutional referendum to abolish the office of the Prime Minister and replace the existing parliamentary system of governance with a presidential system. President Erdogan and his inner circle now make all major political decisions. The ability of Congress to provide checks to his rule is severely limited. (Freedom House, 2019c) |

| 2. Elected officials are chosen in frequent and fairly conducted elections in which coercion is comparatively uncommon | According to the website of the U.S. Senate: “National Elections take place every even-numbered year. Every four years the president, vice president, one-third of the Senate, and the entire House are up for election (on-year elections). On even-numbered years when there isn't a presidential election, one-third of the Senate and the whole House are included in the election (off-year elections).” Coercion in elections is relatively uncommon; however, the 2016 presidential contest featured a significant amount of interference from a foreign power: Russia. (Freedom House, 2019d) | The German Constitution requires that citizens determine the composition of the Bundestag (Federal Parliament) every four years. As stipulated on Germany’s website for the Bundestag, the Basic Law stipulates that members be elected in "general, direct, free, equal and secret elections” (Deutscher Bundestag, n.d.). | The president is directly elected for up to two five-year terms but is eligible to run for a third term if the parliament calls for early elections during the president’s second term. A constitutional referendum passed in 2017 instituted a new presidential system of government, expanding presidential powers and eliminating the office of the Prime Minister (Freedom House, 2019c). |

| 3. Practically all adults have the right to vote in the election of officials | Specific voting laws vary by state, but in general, there are four qualifications to vote in the U.S.: one must be a U.S. citizen, meet the state’s residency requirements, be at least 18 years of age on or before Election day, and are registered to vote by the state’s voter registration deadline (USAGov, n.d.). However, a number of states have partaken in behaviors that disproportionately harm minority voters, such as rolling back early voting, altering polling locations, or enacting laws requiring voters to present specific forms of identification that may be cumbersome or costly to obtain—a provision that disproportionately affects minorities, elderly people, and those with disabilities. In 2018 in Georgia, the registrations of some 53,000 voters—most of them black—were stalled due to applicant information that did not exactly match government records, and hundreds of thousands of other voters had been purged from the rolls for failing to vote in recent elections. (Freedom House, 2019d) | Germany’s constitution gives all citizens age 18 or older the right to vote. This guarantee applies regardless of gender, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity. (Freedom House, 2019b). | According to the Turkish constitution: “All Turkish citizens over eighteen years of age shall have the right to vote in elections and to take part in referenda” (Grand National Assembly of Turkey, n.d., p. 30). |

| 4. Practically all adults have the right to run for elective offices in the government | With regard to running for Congressional office, specific filing processes are set by states, though the Constitution does establish some qualifications for congressional candidates: “No person shall be a representative who shall not have attained to the age of twenty-five years, and been a citizen of the United States, and who shall not, when elected, be an inhabitant of that state in which he shall be chosen” (Filing requirements for congressional candidates, n.d.). | All candidates must be at least 18 years of age. | According to the Turkish constitution: “Every Turk has the right to enter public service. No criteria other than the qualifications for the office concerned shall be taken into consideration for recruitment into public service” (Grand National Assembly of Turkey, n.d., p. 31). |

| 5. Citizens have a right to express themselves without the danger of severe punishment on political matters broadly defined | Americans generally enjoy open and free private discussion. However, a number of threats to this freedom have gained prominence in recent years, related to the collection of communications data and other forms of intelligence-related monitoring on the rights of US citizens by the National Security Agency. (Freedom House, 2019d) | Private discussion and internet access are generally unrestricted, but there have been concerns about government surveillance of private communications. (Freedom House, 2019b) | According to Freedom House (2019): “Many Turkish citizens continue to voice their opinions openly with friends and relations, but more exercise caution about what they post online or say in public. While not every utterance that is critical of the government will be punished, the arbitrariness of prosecutions, which often result in pretrial detention and carry the risk of lengthy prison terms, is increasingly creating an atmosphere of self-censorship. In January and February 2018, hundreds of people, including doctors, construction workers, and high school students, were detained for social media posts criticizing a Turkish military offensive in the Afrin district of Syria.” |

| 6. Citizens have a right to seek out alternative sources of information. Moreover, alternative sources of information exist and are protected by law | The United States has a free, diverse, and constitutionally protected press. The media environment retains a high degree of pluralism, with newspapers, newsmagazines, traditional broadcasters, cable television networks, and news websites competing for readers and audiences. Internet access is widespread and unrestricted. (Freedom House, 2019d) | Freedom of expression is enshrined in the constitution, and the media are largely free and independent. (Freedom House, 2019b) | The government controls most media; according to Freedom House (2019), “The mainstream media, especially television broadcasters, reflect government positions and routinely carry identical headlines. Although some independent newspapers and websites continue to operate, they face tremendous political pressure and are routinely targeted for prosecution.” Opposition parties and candidates therefore have limited chances to convey their campaign messages to voters, and voters have limited access to information, which diminishes their ability to make informed choices at the polls. (HRW, 2018) |

| 7. Citizens have the right to form relatively independent associations or organizations, including independent political parties and interest groups | Citizens are able to form relatively independent associations or organizations. However, the U.S. political environment is highly competitive and dominated by two major parties: Republicans and Democrats. (Freedom House, 2019d) | Citizens have the right to form relatively independent associations or organizations, including independent political parties and interest groups. | According to Freedom House (2019), “Turkey has a competitive multiparty system, with five parties represented in the parliament. However, the rise of new parties is inhibited by the 10 percent vote threshold for parliamentary representation—an unusually high bar by global standards. The 2018 electoral law permits the formation of alliances to contest elections, allowing parties that would not meet the threshold alone to secure seats through an alliance. Parties can be disbanded for endorsing policies that are not in agreement with constitutional parameters, and this rule has been applied in the past to Islamist and Kurdish-oriented parties.” |

| 8. Popularly elected officials must be able to exercise their constitutional powers without being subjected to overriding (albeit informal) opposition from unelected officials | According to Freedom House (2019): “The influence of traditional party leadership bodies has steadily declined in recent decades, while various interest groups have come to play a potent role in the nominating process for president and members of Congress.” Due to the expense and length of political campaigns, candidates are under pressure to raise large amounts of money from major donors This is partly because the expense and length of political campaigns places a premium on candidates’ ability to raise large amounts of funds from major donors, especially at the early stages of a race. While there have been a number of attempts to restrict the role of money in political campaigning, most have been thwarted or watered down as a result of political opposition, lobbying by interest groups, and court decisions that protect political donations as a form of free speech. | The German government is democratically accountable to the voters, who are free to support their preferred candidates and parties without undue influence on their political choices. (Freedom House, 2019b). | With the conversion of the government from a Parliamentary system to a Presidential system, Erdogan and his inner circle make all major political decisions with little opposition and few checks on his power. |

| 9. The polity must be self-governing; it must be able to act independently of constraints imposed by some other overarching political system | While the polity generally is self-governing and is able to act independently of constraints imposed by some other overarching political system, there was an attempt of Wisconsin lawmakers to limit the powers of its incoming governor-elect in 2018. When Republic Governor Scott Walker lost re-election to Democrat Tony Evers, the Republican-controlled state legislature approved new limits on Gov.-Elect Evers’ powers in a lame-duck session. Lawmakers voted to restrict Evers from following through on a campaign promise to remove Wisconsin from a multistate lawsuit challenging the Affordable Care Act; to limit early voting in Wisconsin and make it more difficult for Evers to alter Wisconsin's voter ID law; and to give lawmakers more power over the state's economic development agency, which Evers had said he would like to eliminate (Johnson, 2018). However, a judge struck down the GOP’s laws in March of 2019 (Johnson, 2019). | The polity is able to act independently of constraints imposed by some other overarching political system. | As Erdogan’s control is so centralized to the point that there are few checks on his power, his administration governs without constraints imposed by other overarching political systems. |

Appendix 2.

Source: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, n.d. Accessed May 10, 2019. Retrieved from

https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Humanitarian/Refugees%20%26%20Asylum/

USAP_FlowChart_V9.pdf

Sources

2015 Paris Terror Attacks Fast Facts. (2018, December 19). CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2015/12/08/europe/2015-paris-terror-attacks-fast-facts/index.html

AIDA. (2019a). Dublin - Germany. Asylum Information Database. Retrieved from https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/germany/asylum-procedure/procedures/dublin

AIDA. (2019b). Short overview of the asylum procedure. Asylum Information Database. Retrieved from https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/germany/asylum-procedure/general/short-overview-asylum-procedure

AIDA. (2019c). Short overview of the asylum procedure. Asylum Information Database. Retrieved from https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/turkey/flow-chart

Byman, D., & Speakman, S. (2016). The Syrian refugee crisis: Bad and worse options. The Washington Quarterly, 39(2), 45-60. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.jpllnet.sfsu.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=e0f9f160-b9f7-4a78-81af-9f19be497cb5%40pdc-v-sessmgr01

Cepla, Z. (2019). Fact sheet: U.S. refugee resettlement. National Immigration Forum. Retrieved from https://immigrationforum.org/article/fact-sheet-u-s-refugee-resettlement/

Columbia. (1994, January 12). Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Retrieved from http://www.columbia.edu/~sss31/Turkiye/ata/hayati.html

Connor, P. (2017, October 2). After record migration, 80% of Syrian asylum applications approved to stay in Europe. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/10/02/after-record-migration-80-of-syrian-asylum-applicants-approved-to-stay-in-europe/

Dahl, R. (1982). Dilemmas of pluralist democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press. Deutscher Bundestag. (n.d.). Election of Members of the German Bundestag. Parliament. Retrieved from https://www.bundestag.de/en/parliament/elections/electionresults/election_mp-245694

DW. (2019, May 15). Germany confirms, Syria still unsafe for asylum-seekers. DW. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/germany-confirms-syria-still-unsafe-for-asylum-seekers/a-48742895

Felter, C. & McBride, J. (2018). How does the U.S. refugee system work. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/how-does-us-refugee-system-work

Filing requirements for Congressional candidates. (n.d.) Ballotpedia. Retrieved from https://ballotpedia.org/Filing_requirements_for_congressional_candidates Fischer, M. &Bennhold, K. (2018, July 3). Germany’s Europe-shaking political crisis over migrants, explained. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/world/europe/germany-political-crisis.html

Freedom House. (2018). Germany. Freedom in the World 2018. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2018/germany

Freedom House. (2019a). Democracy in retreat. Freedom in the World 2019. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2019/democracy-in-retreat

Freedom House. (2019b). Germany. Freedom in the World 2019. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/germany

Freedom House. (2019c). Turkey. Freedom in the World 2019. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/turkey

Freedom House. (2019d). United States. Freedom in the World 2019. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/united-states

German Marshall Fund of the United States. (2015). Turkish Perceptions Survey. Retrieved from http://www.gmfus.org/ sites/default/files/TurkeySurvey_2015_web1.pdf.

Gerson, M. (2015, December 10). Germany’s defiant decency in the refugee crisis. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/germanys-defiant-decency-in-the-refugee-crisis/2015/12/10/94c6a81c-9f6d-11e5-8728-1af6af208198_story.html?utm_term=.d679da1fb93f

Goodman, P. S. (2018, August 18). The west hoped for democracy in Turkey. Erdogan had other ideas. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/18/business/west-democracy-turkey-erdogan-financial-crisis.html

Grand National Assembly of Turkey. (n.d.) Constitution of the Republic of Turkey. Retrieved from https://global.tbmm.gov.tr/docs/constitution_en.pdf

Hacettepe University Migration and Politics Research Centre (HUGO). (2014). “Syrians in Turkey: Social Acceptance and Integration.” Report, HUGO, An- kara. Retrieved from http://www.hugo.hacettepe.edu.tr/HUGO-

REPORT-SyriansinTurkey.pdfHindy, L. (2018, September 6). Germany’s Syrian refugee integration experiment. The Century Foundation. Retrieved from https://tcf.org/content/report/germanys-syrian-refugee-integration-experiment/?session=1&session=1&agreed=1

Human Rights Watch. (2018, June 7). Q & A: Turkey’s elections. Human Rights Watch. Retrievedfromhttps://www.hrw.org/news/2018/06/07/q-turkeys-elections#

Humud, C.E., Blanchard, C.M., &Nikitin, MB., D. (2019). Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and u.s. response. (CRS report number RL33487). Retrieved from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/RL33487.pdf

İçduygu, A. (2015). Syrian Refugees in Turkey: The Long Road Ahead. Migration Policy Institute. International Rescue Committee. (2018, December 11). Migrants, asylum seekers, refugees and immigrants: What’s the difference. Retrieved from https://www.rescue.org/article/migrants-asylum-seekers-refugees-and-immigrants-whats-difference

Ishiyama, J. T. (2012). Democracy and democratization in historical perspective. In J.T. Ishiyama, Comparative politics: Principles of democracy and democratization (26-66). Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Johnson, S. (2018, December 15).Wisconsin Lawmakers Vote To Limit Powers Of New Democratic Governor. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2018/12/05/673683966/wisconsin-lawmakers-vote-to-limit-powers-of-new-democratic-governor

Johnson, S. (2019, March 21). Judge Restores Wisconsin Governor's Powers, Strikes Down GOP Laws. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2019/03/21/705536383/wisconsin-governors-powers-restored-after-restricted-by-lame-duck

Kirişci, K., Brandt, J., Erdoğan, M. M., Kirişci, K., Brandt, J., &Erdoğan, M. M. (2018, June 19). Syrian refugees in Turkey: Beyond the numbers. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/06/19/syrian-refugees-in-turkey-beyond-the-numbers/

Kirişci, K. &Sloat, A. (2019). The rise and fall of liberal democracy in Turkey: Implications for the West. The Brookings Institute. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-rise-and-fall-of-liberal-democracy-in-turkey-implications-for-the-west/

Kirişci, K., &Toygür, I. (2019). Turkey’s new presidential system and a changing west: Implications for Turkish foreign policy and Turkish-West relations (Rep.). The Brookings Institution. Le Blond, J. (2018, October 29). German chancellor Angela Merkel will not seek re-election in 2021. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/oct/29/angela-merkel-wont-seek-re-election-as-cdu-party-leader

Livingstone, E. (2016, September 2017). Angela Merkel drops the ‘we can do it’ slogan. Politico. Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/article/angela-merkel-drops-the-we-can-do-it-slogan-catchphrase-migration-refugees/

Mayers, M. M. (2016, May 1). Germany’s response to the refugee situation: Remarkable leadership or fait accompli? Bertelsmann Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.bfna.org/research/germanys-response-to-the-refugee-situation-remarkable-leadership-or-fait-accompli/

Møller, J. &Skaaning, S-E. (2013). Regime types and democratic sequencing. Journal of Democracy, 24(1): 142-155. Office of Refugee Resettlement. (n.d.). History. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/about/history

Ostrand, N. (2015). The Syrian refugee crisis: A comparison of responses by Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 3(3): 255-279. O’Toole, M. (2018, December 20). Syrian war refugees have 'no place anymore' as turkey pushes them to return home. Newsweek. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/2018/12/28/syria-turkey-refugees-erdogan-war-1265789.html

Ozden, S. and Migration Policy Center (2013). Syrian Refugees in Turkey. MPC Research Report 2013/05, MPC, Florence. http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/

Paris attacks: Who were the attackers (2016, April 27). BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34832512

Schmitter, P. C. & Karl, T. L. (1991). What democracy is… and is not. Journal of Democracy, 2(3): 75-88. Schultheis, E. (2019, February 25). Germany is testing the limits of democracy. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/02/german-intel-chief-plan-surveil-far-right-afd/583456/

Shumbert, A. (2015, September 14). Refugee crisis: How Germany rose to the occasion. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2015/09/13/europe/germany-refugees-shubert/index.html

Syrian Civil War. (2019). In Encyclopædia Britannica online. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/Syrian-Civil-War

Taub, A. & Fisher, M. (2018, June 29). In U.S. and Europe, Migration Conflict Points to Deeper Political Problems. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/29/world/europe/us-migrant-crisis.html

The Local. (2019, March 19). European court clears way for Germany to deport refugees to other EU countries. The Local. Retrieved from https://www.thelocal.de/20190319/european-court-clears-way-for-germany-to-deport-refugees-to-other-eu-countries

Turkey: An evolving democracy in the Middle East. (n.d.). Constitutional Rights Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-22-2-c-turkey-an-evolving-democracy-in-the-middle-east

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2018). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2017. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/5b27be547.pdf

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2015). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2014. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/statistics/country/556725e69/unhcr-global-trends-2014.html

United States Senate. (n.d.). Elections. United States Senate. Retrieved from https://www.senate.gov/reference/Index/Elections.htm

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. (n.d.). United States refugee admissions program. Retrieved from https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Humanitarian/Refugees%20%26%20Asylum/

USAP_FlowChart_V9.pdf

U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). Refugee Admissions. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/refugee-admissions/

USAGov. (n.d.). Register to vote and check or change registration. USAGov. Retrieved from https://www.usa.gov/register-to-vote

Vick, K. (2015). Chancellor of the free world. Time. Retrieved from http://time.com/time-person-of-the-year-2015-angela-merkel/

Vonberg, J. (2018, July 6). Why Angela Merkel is no longer the ‘refugee chancellor.’ CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2018/07/06/europe/angela-merkel-migration-germany-intl/index.html

Witte, G. & Beck, L. (2018, August 30). In Germany’s Chemnitz, extremists exploit a killing to take aim at refugees. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/in-germanys-chemnitz-extremists-exploit-a-killing-to-take-aim-at-refugees/2018/08/30/68e31aec-aacc-11e8-9a7d-cd30504ff902_story.html?utm_term=.93d5487df1ae

Witte, G. & Beck, L. (2019, May 5). Angela Merkel welcomed refugees to Germany. They’re starting to help the economy. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/angela-merkel-welcomed-refugees-to-germany-theyre-starting-to-help-the-economy/2019/05/03/4bafa36e-6b60-11e9-bbe7-1c798fb80536_story.html?utm_term=.5f07aac24627

World Bank Report. (2015). Turkey’s response to the Syrian crisis and the road ahead. Zezima, K. (2019, May 7). The U.S. has slashed its refugee intake. Syrians fleeing war are most affected. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/the-us-has-slashed-its-refugee-intake-syrians-fleeing-war-are-most-affected/2019/05/07/f764e57c-678f-11e9-a1b6-b29b90efa879_story.html?utm_term=.f0af06bd7639

Heather McIntyre

MPA Candidate, School of Public Affairs and Civic Management, San Francisco State University

Jorge Contreras

MPA Candidate, School of Public Affairs and Civic Management, San Francisco State University

Phung Nguyen

MPA Candidate, School of Public Affairs and Civic Management, San Francisco State University

Recent Articles

- Models of Public Service Delivery for the Homeless in India: A Comparative Analysis and an Agenda for the Future

- Discussion with H.E. Ambassador Christoph Heusgen

- Round Table Discussion with H.E. Ms. Louise Blais

- China-Iran Deal: A Checkmate to India

- Chinese Belligerence Increases the Number of People Identifying as Taiwanese

- Interview with Sylvia Mishra on India's Defense Relations with Major Powers in the Post- COVID-19 World

- Peering into the future - Economy, Society amd World Politics after COVID-19

- Humanity better off with world order without ‘Chinese characteristics’

- Military Recruitment in the U.S., China, and Russia

- A Comparative Analysis of Key Structures & Responses to the Syrian Refugee Crisis in Germany, Turkey, and the United States

- Analysing the Abrogation of Article 370

- Rethinking India’s Strategic Choices for National Security

- Global Policycast: Geopolitics and Economic changes in Ukraine & Eastern Europe, Christina Pushaw (expert on Eastern European Affairs) in conversation with Arpit Chaturvedi (CEO, Global Policy Insights)

- Syria in ruins as war enters 9th year

- Lord Howell of Guildford’s key note speech at Global policy insight’s seminar on Post Brexit World: UK and the Commonwealth

- A Post - Brexit Britain & India Partnership can Unlock the Potential of the Commonwealth

- Lessons from the Great War : Inevitability versus Institutions

- UK-India Trade Relations: The Long Road Ahead