A Political Economy Analysis of Education in India

Published 24 May 2019 Published by Ritika A Kukreja under Sustainable Development

Why is the universal provision of education still an intrinsic challenge for one of the largest and fastest growing democracies in the world? Despite widespread innovations in global education policy, 84 million children in India remain disengaged from education, and an even greater percentage of students fail to exhibit minimum levels of proficiency. This leads us to question which theoretical lenses may have been under-emphasised, and specifically directs analysis towards the political forces which contribute to our understanding of the scope of education policy in the world’ s largest democracy.

The complex federal framework which characterises the Indian polity presents a context in which policies must be transmitted and sustained through three tiers of government. With a population of over 1.2 billion dispersed across twenty-nine heterogeneous states, the intricate arrangement of politicians and bureaucrats therefore, positions itself as a powerful determinant underscoring the scope of implementation of national policies across the social spectrum. It is therefore essential to discuss the integral role of political institutions in India’s educational progress, and critically assess dominant theories and models which underemphasize the presence of counter-hegemonies within and across the heterogeneous actors in the education system. Societies are not homogenous, and ‘citizens’ cannot be reduced to a single categorical set of actors within the education ‘ecosystem’. Ergo, the core analysis of this article positions itself in a matrix of conflicting interests and power structures between competing actors in education systems.

Despite widespread innovations in education policy across the country - from the Delhi government’s commendable initiatives which improve marginalised families access to private schooling, to the Beti Padhao Beti Bachao (Educate the Girlchild, Save the Girlchild) scheme - the paradox still ensues: Why is the universal provision of quality education still an intrinsic challenge for one of the largest and fastest growing democracies in the world?

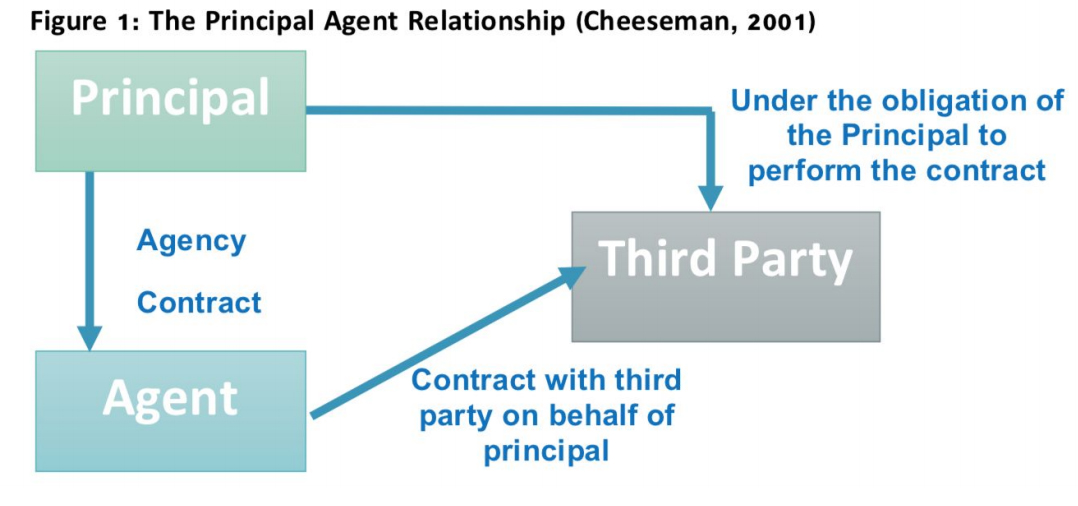

The Principal-Agent Concern and ‘Rational’ Self-Interest

To address this concern, scholars are increasingly deploying various accountability frameworks to unpack and explore the dynamics which create efficient (or inefficient) education ecosystems. In an ideal setting, a Principal-Agent like relationship constitutes of a direct, vertical linkage between the state, educational organisations, and its citizens, or ‘clients’ (parents and students) with its foundations in transparency and accountability (Kitschelt & Wilkinson, 2007). The relationship formulates when the state (the agent) assigns schools and teachers to be the ‘third party’ with decision making powers which reflect ‘the interests of the citizens’ – the principal. Moreover, the agent (politician) is contractually positioned to act on behalf of the principal to represent their needs and wants. If the agent fails to deliver, the principal should be able to monitor this and sanction them until their interests materialise. An illustration of this relationship is presented in Figure 1, below.

However, Aiyar et al. (2015) advocate the need for a shift in our conceptual understandings of why policies fail by employing a political economy framework to uncover why education policy implementation tends to distort and illustrates this using the example of Bihar. By exploring the cognitive elements inherent in the day-to-day decisions of political actors at various reform levels, such research can shed light on the roles that rationality and conflicting interests play in determining the scope of policy. Through a rudimentary political economy lens, state actors are driven by self-interest, with a desire to maximise their own power at any given opportunity. Assuming their interest rests in being re-elected by the populace, they are incentivised to support the demands of the ruling elite, whilst under electoral compulsion to extend the reach of developmental policies to socioeconomic pariah’s. Likewise, Riddell (1999), and Grindle (2004) evaluate policy implementation as a form of agenda setting to explore the interactions and negotiations which ‘shape or alter’ the political agenda for education, and the relative powers of alternate interest groups.

Equally, deviations are continually observed in the efficacy of policies and their true reach. For instance, one of the most commended education policy innovations in India – the Midday Meal scheme - fails to reach about 25% of its intended beneficiaries nationally, even though it advocates the supply of free school meals for all children in government or state-assisted schools6 (TOI, 2016). Along the intricate bureaucratic structure characteristic of the Indian polity, the policies designed at the national and state levels are simply not reaching the intended beneficiaries. In each stage of policy implementation, discrete opportunities are presented to bureaucrats to act in their ‘rational’ self-interest, at the expense of the beneficiaries. For instance, in defining conflicting objectives on the macro-level, political forces continue to interfere in the implementation of education policies when, for instance, state governments held by opposition parties refuse to assist or publicise education progress, in apprehension that the central government will accrue credit for their efforts (Majumdar & Mooji, 2011).

These analyses thus adopt a broad and systematic perspective, whereby the conflicting intents of diverse actors in the education system account for the distortion of policy implementation, particularly critiquing the negative space occupied by the ‘self-interested’ bureaucrats. In advocating for greater accountability between citizens and the suppliers of education to minimize these distortions, scholars are increasingly emphasizing on the need to reorganise the education system to facilitate a diffusion of power back to the community (Pritchett, 2015). However, these arguments rarely delve into scrutinizing the conflicting interests within communities, instead grouping ‘public interests’ as a homogenous domain. Social reality, in contrast, is far from homogenous.

Proposed Reduction of the State

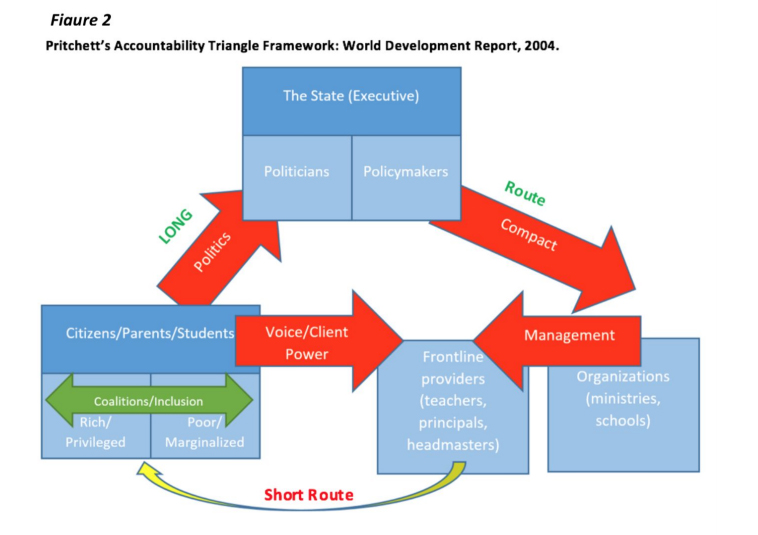

In advocating for greater accountability between citizens and the suppliers of education to minimise these distortions, Pritchett (2015) designs a comprehensive framework for and argues that a reduction of the state’s involvement in education practices and the subsequent decentralisation of education, will facilitate greater accountability between customers (students and parents), and immediate suppliers (schools and teachers). In conceptualizing accountability between the state, citizens and ‘suppliers’, Pritchett proposes four ‘design elements’ of policy structures, which need to work in coherence in order to produce optimal outcomes in learning for students. He argues that the inconsistency in the objectives of actors in the education system creates a closed and incoherent education system which is centred around schooling, as opposed to learning (p. 4; 2015) The centrality of this lies in the reasoning that the state fails to delegate ‘learning’ as an objective to the school management, and constructs limited avenues to measure the true efficacy of their initiatives, and hold education providers accountable for their desired outcomes.

,p>Pritchett further denigrates the role of the state by highlighting the inconsistencies between two of his elements – delegation and finance – whereby the “insufficiency of resources relative to goals means that there will be gaps between the actual accomplishments and the delegated objectives” (2015), which essentially allows ministries to attribute the lack of resources as the reason for their failure to implement policies in their provinces. Additionally, he accredits the presence of both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ schools within the same community, to the coherency (or lack of) in the shared objectives of the actors involved, and the (in)ability to measure these objectives.In an ideal setting, greater accountability can be achieved if one adopts the ‘short route’ whereby the relationship between citizens and education organizations facilitates a more efficient transmission of citizen voice by directly engaging with the frontline providers of education, who can be rewarded or reprimanded by both citizens and higher organizations, contingent upon the learning outcomes produced. In essence, this framework endeavours to confer power back into the “community” through the reduction of state intervention, shown in Figure 2 below.

The paradox hence remains that despite the subsequent reduction in state involvement in education, the world’s largest democracy still fails to extend ‘accountability’ to its most deprived communities. The inherent concern is that much of the analysis which argues for the privatisation of education, incessantly regards ‘citizens’ as an uncontested, homogenous group of principals. The assumption that these citizens are characterised by similar intents, powers, and demands is what skews our current understanding of policy implementation. In India’s social reality, accountability cannot simply be facilitated by adopting the ‘short route’, since an array of deeply intrinsic social stratifications exist; principals are divided by caste, class, gender, religion, ethnicity and even culture in various stances.

In a context characterized by conflicting principals with diverging powers in their voice, it is inevitable that those at the top of the social hierarchy will be able to better communicate their interests than their counterparts. Due to this, the ‘principal-agent’ relationship naturally collapses.

For instance, consider the following scenarios:

1. ‘Inclusion’ of socioeconomically weaker pupils in the education system

Recent initiatives to integrate socioeconomically weaker children into all of Delhi’s private schools have been devised. Despite a multitude of positive externalities this engenders in terms of access to quality schools, (peripheral) inclusion, and exposure, the key space which continually fails to be recognised is an understanding that students’ social identities and capabilities are not uniform - both within and across the socioeconomic arena, and this is a crucial position to absorb and secure within any (education) policy framework. In evaluating this policy using the instrumental human capabilities framework presented by Amartya Sen (1985) and Martha Nussbaum’s (2003), what we learn is that superficially integrating marginalised students into ‘quality’ private schools are likely to engender consequences which impede the success of such policies.

For instance, a student from a relatively deprived background who is entering the private education domain for the first time, is the first generation learner in his/her household will inevitably require the use of an alternative pedagogy and learning environment in order to maximise his/her ability to learn the same curricula as their peers, as they exhibit differing after-school support structures and activities, altering literacy absorption skills, speeds and methods. Ergo, their needs and wants are likely to differ tremendously from their peers, resulting in the school management needing to respond to the varying demands of students and parents from socioeconomic groups which are constellations apart. Given analyses concerning rationality and conflicting interests, within this scenario - where the demand for private providers of education largely constitutes the voices of those who can afford the fees and simultaneously hold the management accountable - it is thus likely that greater responsiveness will be directed towards children from upper classes/castes, coming from relatively elitist families whose bargaining power subsumes that of the parents of lower class/caste children in the same school and education system.

Similarly, if we step away from the analysis of individual policies and employ a macro-perspective to the increasing privatisation of education, what we continue to observe is that the education system is being dominated by private schools which are enacted to serve the middle- and upper-class classes, with only a limited number of high quality schools investing in, or occupying space exclusively for the weaker sections of society. This has consequently led to deepening inequalities in the learning outcomes and educational experiences of upper class children and their counterparts while the needs of parents from marginalised communities constitute extremely limited participation in such a system.

2. Accountability for whom?

The principal-agent (PA) relationship depicted above requires the absence of barriers which impede transparent access to the agent or third party’s performance. Herein lies the primary barrier in achieving ‘accountability’ towards suppliers of education for citizens from marginalized backgrounds (slum residents). The push towards ‘accountability’ in bureaucracy or in private settings are terms not even understood by much of the marginalised populace. For many of the families in socioeconomic turmoil, the children currently enrolled in school are first generation learners, ergo their parents possess limited conceptual understanding as to what ‘good’ education is; information asymmetry exists (RISE, 2017). Without foremost possessing a sufficient amount of information based on how schools should be, they are less likely to be able to reprimand or judge the actions of the third party (schools, teachers, ministries etc.). They ultimately do not retain sufficient mobility to send their children to ‘better’ schools, ergo, in instances where teacher absence is extremely high leading to children getting disengaged from education. Coupled with the lack of information available to these families, marginalised families do not possess the power and status driven tools to reprimand defections from the school, constraining them to a schooling environment which demonstrates questionable quality and limited avenues to hold the school management accountable. Middle and upper-class families however, demonstrate greater bargaining power, access and retain more transparent information, and are in a stronger position to directly demand their right to education services and explore available sanctions if the bureaucrat or school fails to deliver. The voices of the urban poor are seldom heard, rather they are silenced by the interests of the dominant elites.

The concern explored in this article stems from the inevitable presence of socioeconomically segmented principals in various emerging economies. In relation to the Indian context, inequalities in opportunity, along with differing skill levels as a result of social stratification has exasperated social cleavages and thus resulted in a ‘double burden’ of development. Given the presence of these social divisions, politicians contesting for electoral dominance and private organisations penetrating the education system are compelled to appeal to the various emerging classes in the country/state. Likewise, schools – both private and government run – need to be responsive to an array of heterogeneous students and parents who ‘rationally’ seek to maximize their own interest whilst inhibiting the uprising of the other. The discrepancies in the classic principal-agent relationship demonstrate the incompatibility of the accountability triangle with the social realities we observe today.

Accountability is an instrumental pillar for democratic governance - both at a political level, and one which is intrinsic to the social institutions supporting the nation. Ergo, given the incessant paradox, how can we identify, construct and maintain effective means of accountability in education for the socioeconomic pariahs of the world’s largest democracy? Perhaps we need to unpack and reconstruct our notions of what ‘democracy’ and ‘accountability’ are in their essence, and how they manifest across the divergent socioeconomic constellations which characterise the Indian polity

Find out more in the next article of this series on 'Accountability in Education' curated by Ritika

A.Kukreja References and Sources of Information:

Aiyar, Y., Dongre, A., & Davis, V. (2015). Education reforms, bureaucracy and the puzzles of implementation: A case study from Bihar. International Growth Centre.

Auerbach, A. (2014). “Clients and Communities: The Political Economy of Party Network Organization and Publications Development in India’s Urban Slums.” World Politics 68, no. 1 (January 2016): 111-48.

Biesta, G. (2004). Education, Accountability, and the Ethical Demand: Can the Democratic

Potential of Accountability Be Regained?. Educational Theory, 54(3), 233-250.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-2004.2004.00017.x

Borah, R. (2012). Impact of Politics and Concerns with the Indian Education System. International Journal of Education Planning & Administration. Research India Publications, 2 (2), pp.91-96

Census of India Website : Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. (2011). Censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved from http://censusindia.gov.in/

Cheeseman, H. (2001). Business law. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Dyer, C. (1994). Education and the state: Policy implementation in India's federal polity.

International Journal Of Educational Development, 14(3), 241-253.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0738- 0593(94)90038-8

Grindle, M. (2004). Despite the Odds: The Contentious Politics of Education Reform. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40751249

Jha, S. Rao, V & Woolcock, M. (2007) "Governance In The Gullies: Democratic Responsiveness And Leadership In Delhi’S Slums". World Development 35.2 230-246.

Kingdon, G. and Muzammil, M. (2003) The Political Economy of Education in India: Teacher Politics in Uttar Pradesh (Delhi: Oxford University Press).

Kingdon, G. and Muzammil, M. (2009) A political economy of education in India: the case of Uttar Pradesh. Oxford Development Studies, 37(2), pp. 123–144.

Krishna, A. (2006).”Poverty and Democratic Participation Reconsidered: Evidence from the Local Level in India”. Comparative Politics, 38(4), 439. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/20434011

Kingdon, G., Little, A., Aslam, M., Rawal, S., Moe, T., Patrinos, H., Beteille, T., Banerji, R., Parton, B. and Sharma, S.K. (2014). A rigorous review of the political economy of education systems in developing countries. London: EPPI-Centre, of Education, University of London

Kitschelt, H. & Wilkinson, S. (2007). “Patrons, clients, and policies” (1st ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Krishna, A. (2008). “Poverty, participation, and democracy” (1st ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Majumdar, M. (2005). The Political Economy of Education in India: Teacher Politics in Uttar

Pradesh. Contemporary Education Dialogue, 2(2).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/097318490500200208

Majumdar, M., & Mooij, J. (2011). Education and inequality in India. Oxon: Routledge.

Nussbaum, M. (2003). CAPABILITIES AS FUNDAMENTAL ENTITLEMENTS: SEN AND SOCIAL JUSTICE. Feminist Economics, 9(2-3), pp.33-59.

Priyam, M. (2015). Contested politics of educational reform in India. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Raghavan, P. (2016). Why does midday meal scheme exclude a large number of children in the poorest states?. Times of India Blog. Retrieved 28 November 2017, from https://blogs.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/minorityview/why-does-midday-meal-schemeexclude-a-large-number-of-children-in-the-poorest-states/

Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE). (2017). Retrieved from http://www.riseprogramme.org/sites/www.riseprogramme.org/files/Ethiopia%20CRT%20Overvi ew_0.pdf

Robinson, J. (2005). Despite the Odds: The Contentious Politics of Education Reform. Perspectives On Politics, 3(01). http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s1537592705480147

Pritchett, L. (2015) Creating Education Systems Coherent for Learning Outcomes: Making the Transition from Schooling to Learning. RISE Working Paper 15/005.

Riddell, A.R. 1999. ‘The Need for a Multidisciplinary Framework for Analysing Educational Reform in Developing Countries’, International Journal of Educational Development, 19: 207–17.

Sadgopal, A. (2010). Right to Education vs. Right to Education Act. Social Scientist, 38(9/12), 17-50. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27896288

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

World Bank. 2003. World Development Report 2004 : Making Services Work for Poor People.

World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5986 License:

CC BY 3.0 IGO.”

Ritika A Kukreja

Ritika A Kukreja is a Research Coordinator at Global Policy Insights, with a focus on Sustainable Development. Prior to joining GPI, Ritika graduated with an MPhil in Education and International Development from the University of Cambridge, and also holds a Bachelors in International Development from King's College London, during which she directed her research towards analyzing grassroots democratic institutions and informal political networks in India's most deprived neighborhoods.

Recent Articles

- Hon Anġlu Farrugia, Speaker of the House of Representatives Parliament of Malta & Secretary General CPA Small branches speaks to Uday Nagaraju, Executive President & Co-founder of Global Policy Insights on Commonwealth, CPA Small branches and Parliament of Malta

- Global Policycast: Geopolitics and Economic changes in Ukraine & Eastern Europe, Christina Pushaw (expert on Eastern European Affairs) in conversation with Arpit Chaturvedi

- Cyprus High Commissioner to the UK H.E Euripides L Evriviades interviewed by Uday Nagaraju

- A Political Economy Analysis of Education in India

- Syria in ruins as war enters 9th year

- Environmental Finance — Private Capital and Private Profits for Public Gain — Promising, but not without Pain

- A Review of Indo-Swiss Trade: Strategic Priorities from a Realist Perspective

- Global Policycast: Ex-Minister of Youth, Paraguay- Magali Caceres interviewed by Arpit Chaturvedi, C.E.O Global Policy Insights.

- Akbar Khan speaks about promoting parliamentary strengthening and inclusive democracy in Commonwealth Parliaments.

- “Geopolitical Change and Risk in Venezuela”: Jose Chalhoub interviewed by Arpit Chaturvedi, CEO Global Policy Insights

- Lord Howell of Guildford’s key note speech at Global policy insight’s seminar on Post Brexit World: UK and the Commonwealth

- A Post - Brexit Britain & India Partnership can Unlock the Potential of the Commonwealth

- Lessons from the Great War : Inevitability versus Institutions

- UK-India Trade Relations: The Long Road Ahead